John Gould (1809-1881) was an English ornithologist. Gould is often referred to as the John Audubon of England, which may be a fairly apt characterization since Audubon (born in 1785) was nearly a quarter-century older than Gould.

Gould was born in Lyme Regis, England, the first son of a gardener whose name has been lost to history. It is likely that neither father nor son had much formal education, hence they should be given high credit for their achievements. Later in life, the senior Gould was the foreman in the Royal Gardens at Windsor and the younger, after developing a reputation as London’s most skilled taxidermist, became the first curator at the museum of London’s zoological society.

Gould’s position at the zoological society brought him in contact with many famous naturalists of the era. In 1830, it was one such individual whose donation of several never before described Himalayan birds caused Gould to publish his first ornithological monograph. The work was a true collaborative effort supervised by Gould, written by Nicholas Vigors, and illustrated by lithographs done by Gould’s wife Elizabeth Coxen.

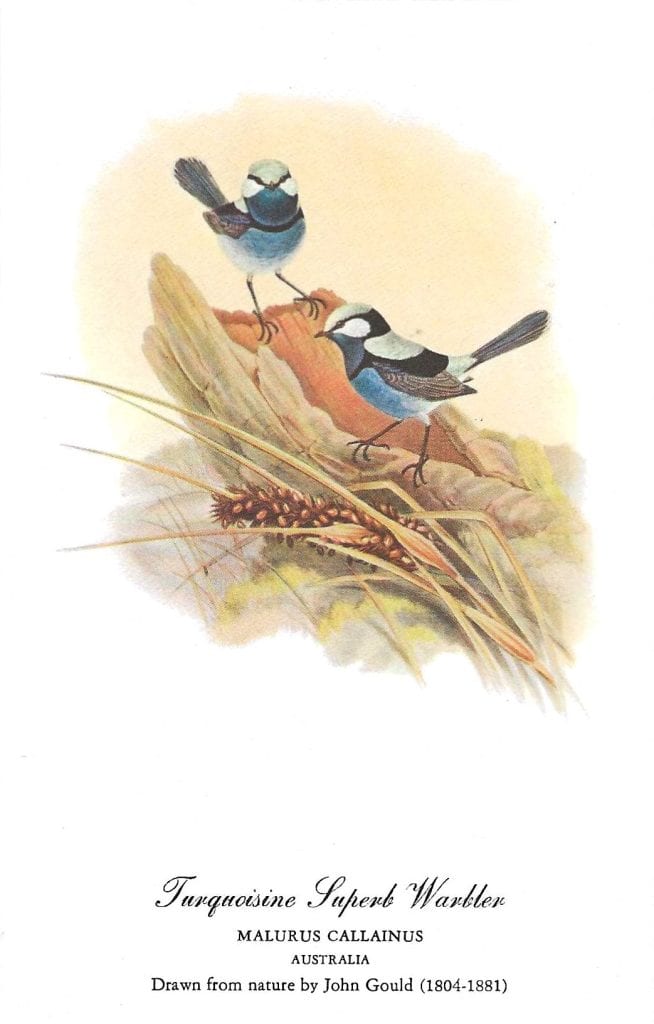

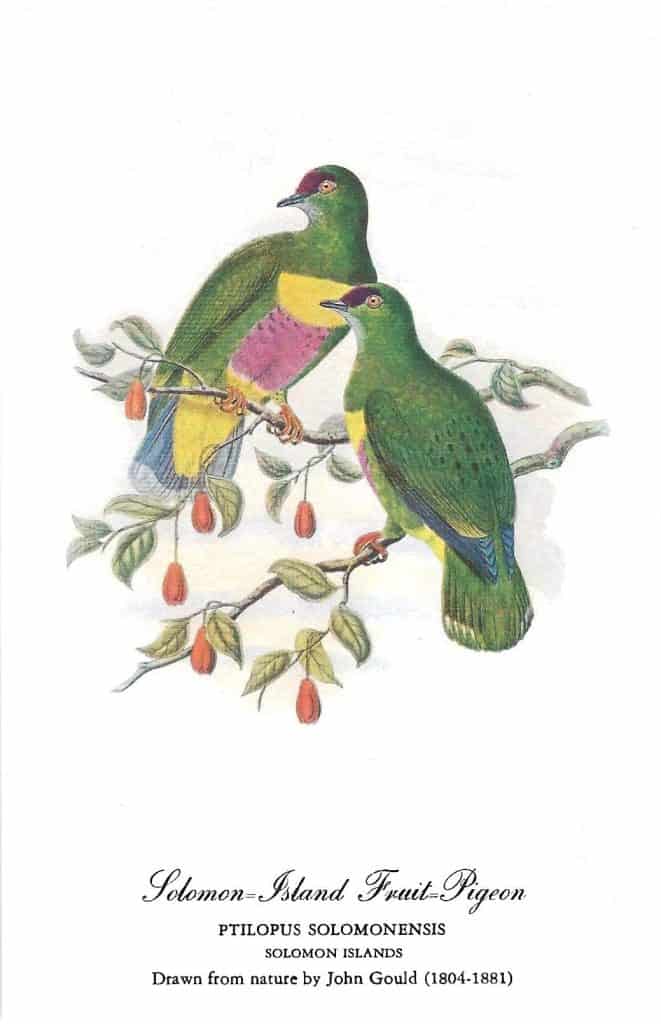

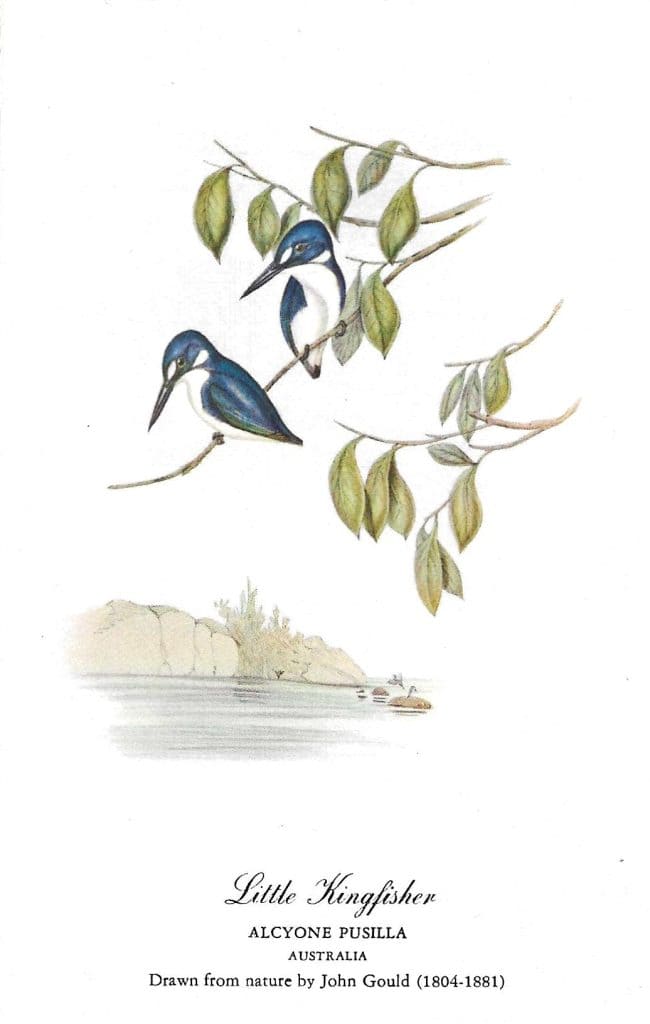

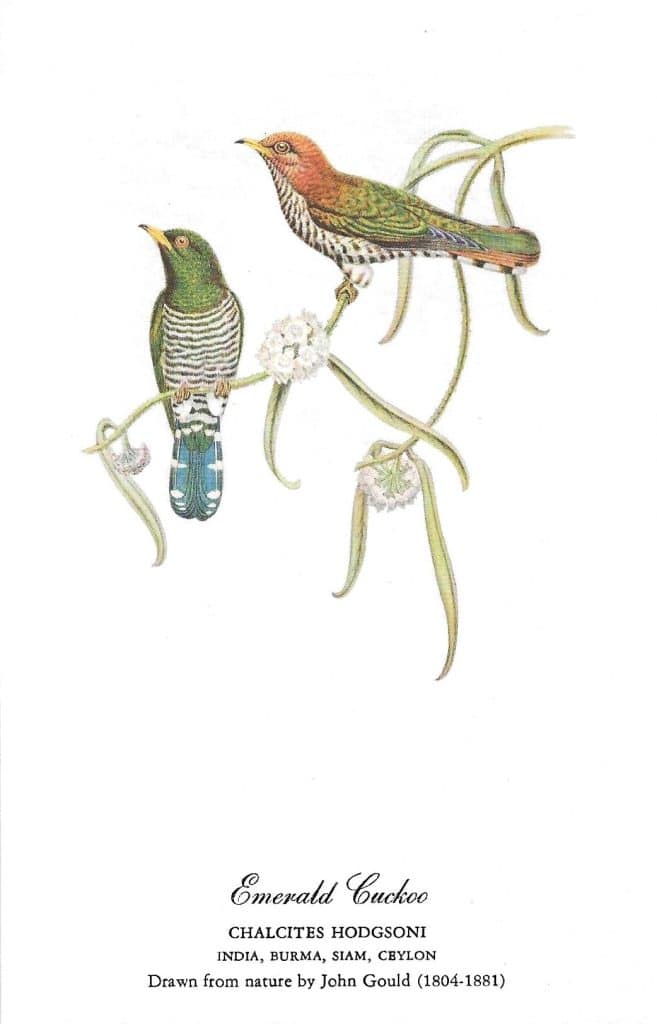

Gould’s artistic skills were always in doubt, but his creative expression and illustrative design were unquestionably accurate. His efforts ended as rough sketches on paper from which other artists created the lithographic plates that have remained the United Kingdom’s most accurate record of the world’s wildlife.

The achievements of John Gould are numerous and his connections are many, including a working relationship with the one-and-only Charles Darwin. When Darwin returned to England in 1837, after the second voyage of the H.M.S. Beagle, he presented his collection of specimens to the zoological society. The bird specimens from that donation were given to Gould to identify. He later reported on Darwin’s collection as one of the world’s most significant advancements in regard to species identity.

After his work with Darwin, Gould sailed to Australia, primarily to be the first to identify the birds from that continent. It is this period in Gould’s life that the drawings mentioned in this essay were done.

One relevant point about Gould’s career is fascinating. His biographer wrote: Throughout his professional life, Gould had a strong interest in hummingbirds. He accumulated a collection of 320 species, which he exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1851. Despite his interest, Gould had never seen a live hummingbird, but in May 1857, he travelled to the United States with his son Charles. He arrived in New York too early in the season to see hummingbirds in that city, but on May 21, 1857, in Bartram’s Gardens in Philadelphia, he finally saw his first live one, a ruby-throated hummingbird. He then continued to Washington D.C. where he saw large numbers in the Capitol Gardens. Gould attempted to return to England with live specimens, but as he was unaware of the conditions necessary to keep them, they only lived for two months at most.

It was more than a half-century later when the Barton-Cotton Company of Baltimore, Maryland chose to publish the Gould lithographs on postcards.

Barton-Cotton Company’s Postcard set of John Gould’s

Australian and Asian Birds

Other Titles in the set are:

Graceful Wren

Wire Tailed Swallow

Black Crested Tit

Guerin’s Helmet Crested Hummingbird

The Beautiful Grass Finch

Bevan’s Bull Finch

***

This brings us to why this article has such a seemingly indifferent and insulting title.

The cards were purchased earlier this year and have become part of the author’s collection. These like any other postcards enjoy a beauty that is truly “in the eye of the beholder.” The cards in my collection are seldom shared with non-postcard collectors, but these were an exception. A bird watcher friend visited to celebrate a family birthday and the cards were shown to him with the expectation that he would enjoy the artwork and the variety of presentation. His reaction was at best, nonplussed. Maybe even puzzlement, bewilderment, or indifference.

My friend is never casual in opinion and is a man who speaks his mind. After a three, maybe five-minute study of the twelve cards, he turned to me and said, “The only message I could think to write on cards like these is, Sorry to hear your parakeet died.

Beautiful cards! Your friend’s funny comment on your cards was what caught my attention. It brought back a nice memory. My family had a pet parakeet with a big personality. When “Peaty” died at the ripe old age of 16 years my mother prepared a little casket with a white satin bed in an Altman’s red and white box, sealed in aluminum foil. The local kids then had a funeral parade to the backyard where he was buried under a bush, complete with prayers.

Thank you The tie in with Darwin and the ties with Australia and England And it alll seemed to fall into place

Thank you

I noticed that of the four countries identified as the range of the emerald cuckoo, only India is still known by that name. Burma is now Myanmar, Siam became Thailand, and Ceylon was replaced by Sri Lanka.