PHILADELPHIA, Pa. December 1968

Marty Joseph was a bookman in every regard. To him every book was a scholarly epistle made to help the reader learn. Marty and I shared that opinion and although he was likely twelve to fifteen years my senior, we often took on self-created missions that could have been described as educational crusades. This is the story of one such mission that failed, but one that taught us a good lesson.

Marty worked at his own company as a book-jobber for school libraries. He spent much of his weekends editing and proofreading unsolicited manuscripts for a New York enterprise (one of those companies with three names that sound more like a law firm than publishing house).

One day, over fifty years ago, Marty invited me to have lunch with him while he interviewed a new author who had worked more than three decades as a skywalker. Jamie Yellowhorse was a Native American. He had submitted his autobiography to a New York publisher through a “dime-a-day” agent. Marty had read the manuscript; I had not. As I settled into the passenger’s seat of Marty’s new, jet-black Lincoln Continental, he handed me the book and asked me to peruse it and be ready to tell Jamie how it could be improved and what edits it needed for publication.

Marty drove out of his Germantown parking lot and headed across north Philadelphia and started up the ramp onto Interstate 95 North. This surprised me enough to ask where lunch would be. Without hesitation, “Greenwich Village” was his reply; “it’s only 75 minutes away. That will give you an hour to read Jamie’s book.”

I sat and read for the next half-hour and grew more uneasy as I turned each page. Marty asked if it was salvageable. My reply was simple, “No. It’s a book that will never find an audience.”

That was the day I learned about Iron in the Sky – a working title for Mr. Yellowhorse’s autobiography. Sad to say, I never saw Mr. Yellowhorse again, his book was never published, and the “proof” copy, still in my possession may be the only remaining evidence of Jamie’s autobiographical effort.

When the term skywalker is mentioned as an occupation it is often thought to be a job description assigned to any Native American who goes into ironwork. This is not true, it’s mostly Iroquois, specifically Mohawks from the Kahnawake reservation near Montreal who earn the title. But there are exceptions – namely those who are members of the Sioux tribes from the northern states in the American mid-west.

Jamie was a second-generation construction worker. The first and second chapters of his book tell of the nature and responsibilities of the job – including the degree of danger and the unusually high salaries paid to compensate for the risk. A very poignant passage is found in Chapter Two where he describes the family dynamic while his father was “away-at-work.”

It was still difficult to read Iron in the Sky, but as I read, several thoughts raced through my brain that there was a Postcard History story in its pages. The subsequent chapters fill in details of the jobs Jamie had from around 1925 to November 1967. Jamie’s working years on high-iron projects ended when he installed his last rivet in an I-beam in the framework of World Trade Center One. Most of the stories are routine and mundane, others are funny, and a few are sad.

If a story was to be found, the first step would be to find postcards of the job sites where John Yellowhorse and his son, Jamie had worked. Six were found; one showing John’s work and five of Jamie’s.

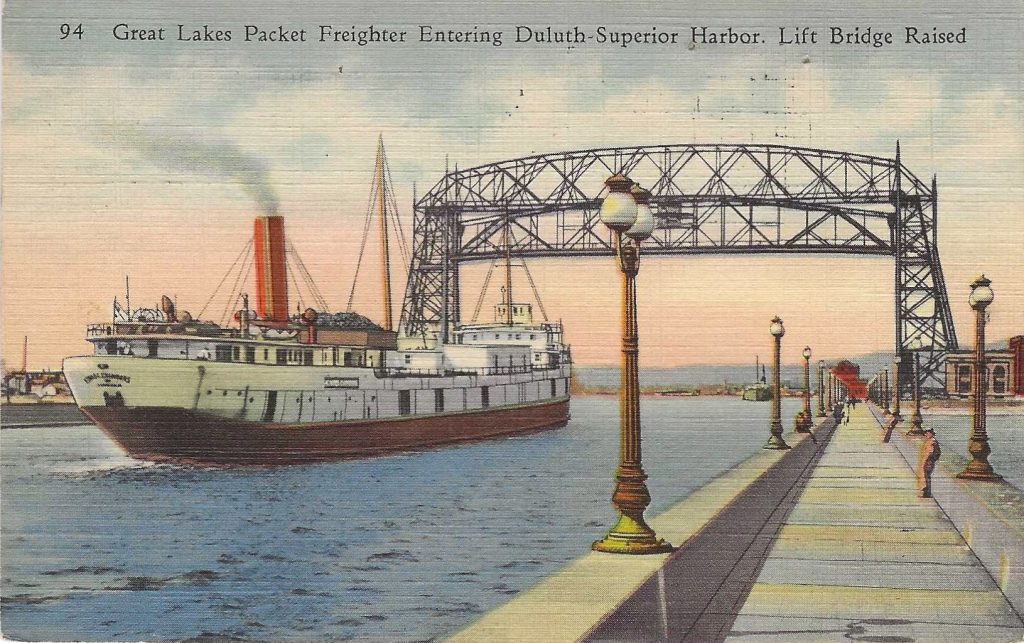

1905 The Duluth (Minnesota) Harbor Lift Bridge

When Jamie was born in 1906, his father was working in Minnesota. John Yellowhorse never held a supervisory job, but he was the leadman of the daytime crew constructing the Duluth Harbor Lift Bridge.

The bridge first served the City of Duluth in 1905. It started as an Aerial Ferry Bridge but in 1929 it was converted to a vertical lift – one of less than ten in the world. It became a National Landmark in 1973.

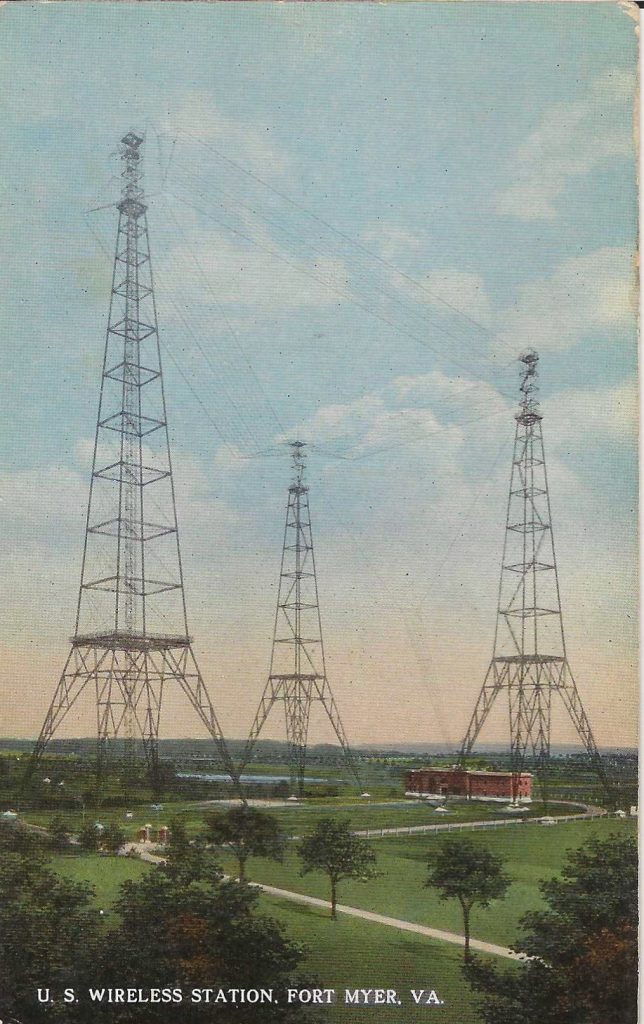

1913 The U. S. Wireless Station at Fort Myer, Virginia

The United States Navy established their wireless station at Fort Myer, Virginia, in 1913. When the “Three Sisters” towers were complete they were the means by which the first radio telecommunications broadcast was made from Washington, D.C., to Paris in 1915. The first ever message to cross the Atlantic Ocean.

Jamie Yellowhorse worked there as a civilian tower maintenance man for several months in 1925 and 1926.

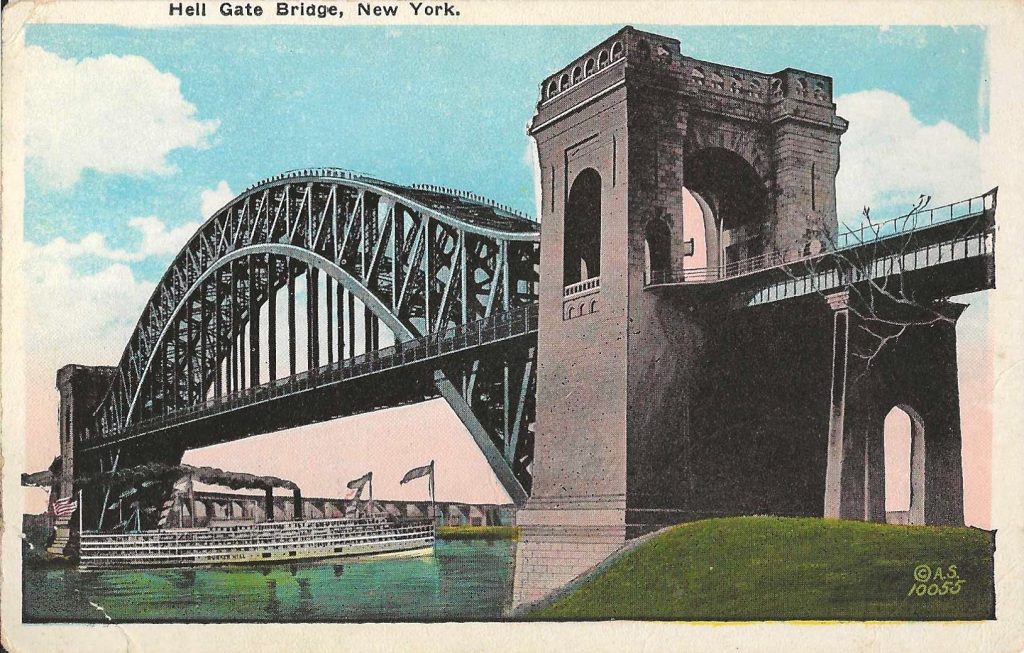

1916 The Hell Gate (Railroad) Bridge in New York

In the late summer of 1926, a maintenance report on the Hell Gate Bridge was published on the ten-year old railroad bridge. A team of skywalker Americans was hired to correct the defect. At the last minute a position opened. Jamie Yellowhorse applied and by mid-September Jamie had moved to New York. He claimed it to be a good job, but not a great one, since the work site was harsh.

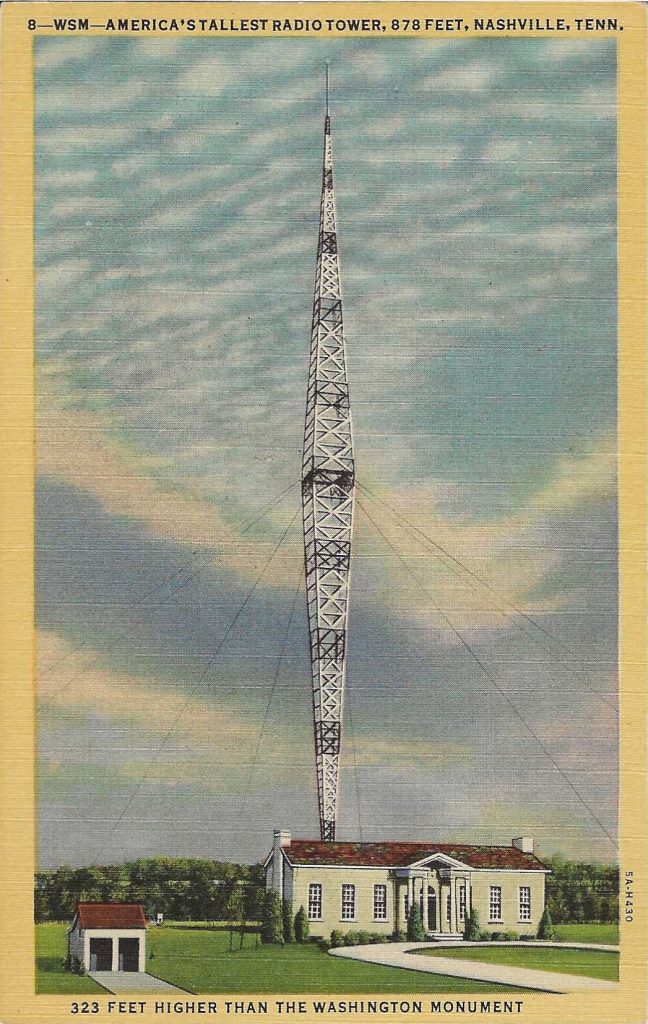

1932 The WSM Radio Tower in Nashville, Tennessee

Supposedly the most fun Jamie ever had at work was in Nashville, Tennessee. It was sad that the job lasted only one year, because the pay was good, his crew mates were all “grand-guys” and the boss was fair with the assignments and free-handed with the privileges.

The 808-foot-tall, WSM-AM broadcast tower was erected in 1932. Even before it was complete, the station was designated as one of the fourteen national clear channels – that had permission to transmit at full power at night. It became the radio home of the Grand Ole Opry.

Jamie wrote that while he worked at WSN, one side benefit was the singing lessons he got for free from the Opry Men.

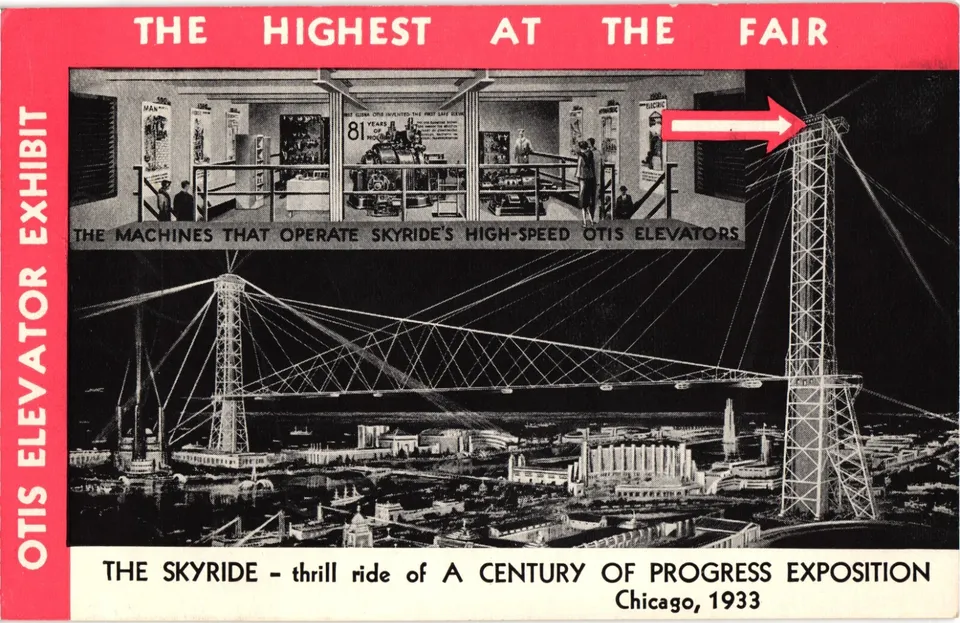

1933 Chicago World’s Fair Sky Ride

My friends and especially my wife thought that I had gone crazy when I applied for a job with an elevator company. I guess they thought I would stand in an elevator and push buttons all day. That was not to be. I got to put the finishing touches on the Otis cars that carried passengers up to and down from the Sky-Ride at the Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago.

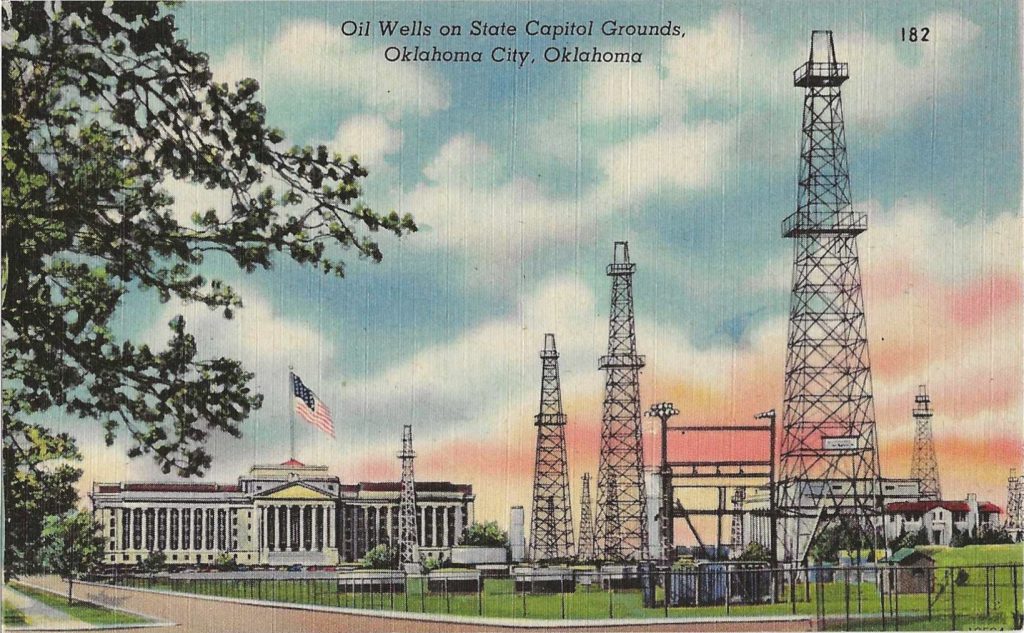

1941 Oil Wells on the front lawn of the Oklahoma capitol building.

In the 10th Chapter of Iron in the Sky, Jamie wrote, “I was mad as hell when I heard what happened on December 7, 1941. It was my day off from work at Petunia #1. I wanted to join the Army and go to the Pacific to shoot J _ _ s.”

My wife had other thoughts. Petunia #1 turned into a #2 and much more. I worked there for nine years. I set a new personal record. I managed to buy a house, two new cars, and we sent our children off to college – Niaha became a teacher; Jesse graduated with an MD and practiced in western Missouri.

Life’s mission accomplished. We left Oklahoma in 1964, never to return.

Another great article that illustrating a person’s life through postcards.

Thank you for this information about the Hell Gate Bridge. I have ridden over it many times on train trips from Philadelphia to Boston. I even have a 4′ model of it in my “train room” at home.

Thank you for the great article. Workers on high steel and especially skywalkers are amazing. I pass the WSM-AM tower occasionally. It is nice to know that its construction was fun at work.

Such an interesting story through the postcard lens. Thanks for sharing it.

Ray always writes lovely introductions to his stories.

I never realized there were aerial ferry bridges or vertical lift bridges until today, although I have long known of drawbridges.