Naming hotels for famous individuals suggests approval from that esteemed person and gives the hotel a cachet. In New York City there was the Hotel Governor Clinton named for the first governor of the Empire State. Philadelphia had the Benjamin Franklin Hotel, named for one of the founding fathers. Raleigh, North Carolina, had the Sir Walter Raleigh named for the famous English explorer, military leader, and statesman. Richmond, Virginia, has the Hotel Jefferson named for the third president of the United States. Hollywood had the Roosevelt Hotel (named for Teddy not Franklin nor Eleanor.) San Diego has the US Grant named for the famous Civil War general and 18th United States President. Dotting the American South were lodging establishments named for Grant’s Civil War opponent, General Robert E. Lee.

During the 1920s, grand hotels were erected in small towns and large cities across the United States. This boom period for hotel building ended during the Depression when 80% of the hotels in the country defaulted on their mortgages.

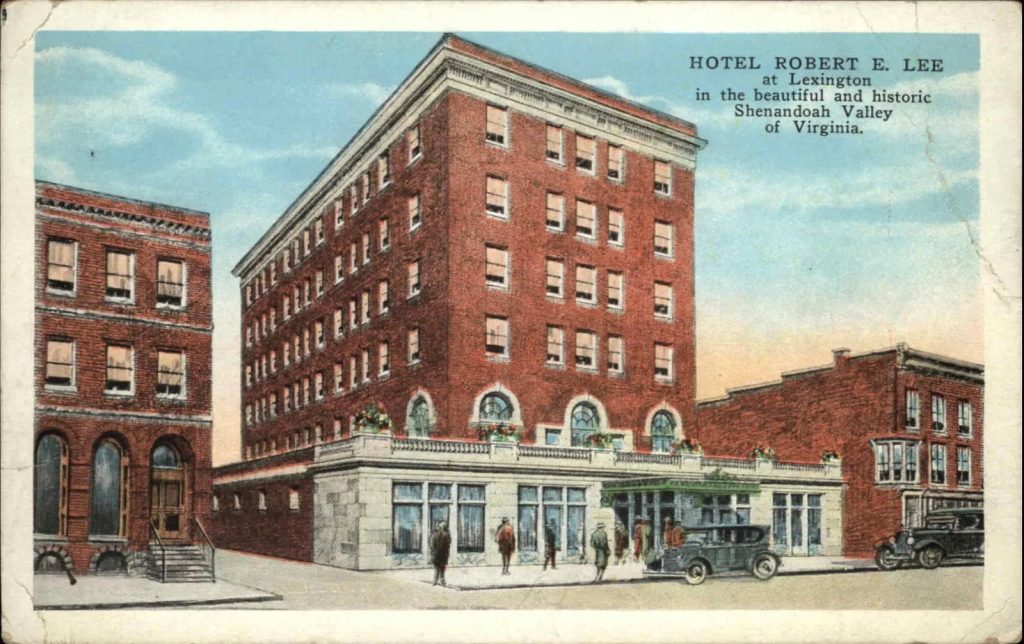

The Robert E. Lee Hotel in Lexington, Virginia, opened in 1926. At six stories, the hotel is still the tallest building in Lexington and offers stunning views of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Lexington is the home of the Virginia Military Institute and Washington and Lee University. Lee served as President of Washington College after the Civil War until his death in 1870. U.S. Route 60 (East – West) and Route 11 (North – South) intersected in downtown Lexington ensuring a steady stream of travelers to the Robert E. Lee. The hotel declined as travelers’ tastes changed and Interstates 81 and 64 bypassed the downtown. In the late 1960s the Lee Hotel was converted into an apartment house. In 2014, the building underwent a complete renovation and reopened as a boutique hotel with thirty-nine guest rooms and suites. It was rebranded as the Gin Hotel and is affiliated with the Choice Hotels Ascend Collection.

This 1950s postcard portrays the Robert E. Lee Motel in Bristol, Virginia. It was located five miles east of Bristol on U. S. Route 11, a major north-south highway in pre-interstate days. Colonel Harlan Sanders operated the second-floor restaurant in the early 1950s (see inset). Route 11 from New Market, Virginia, to Bristol was named Lee Highway in the general’s honor. The motel was built in the 1940s and closed in the ‘90s. The structure was demolished in 2009 and only its iconic neon sign survives. Moved about a mile down the road to a self-storage facility, the sign was refurbished minus the lighting.

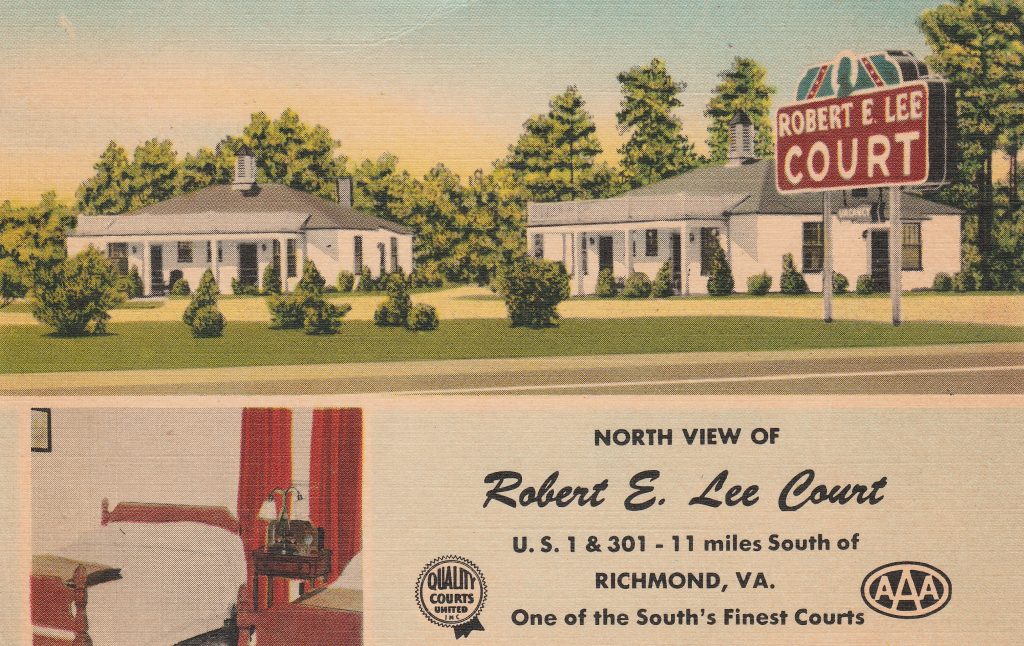

Route 1/Route 301 south of the James River was named Jefferson Davis Highway and was dotted with motels and tourist courts like the Robert E. Lee Court. The caption on the back proclaims that the Robert E. Lee is ultra-modern and new throughout with four air-conditioned rooms (out of forty) and was one of the South’s finest courts.

In order to speed traffic through Richmond and relieve congestion (the combined Route 1/Route 301 through Richmond was only four lanes and much of it was undivided), the Commonwealth of Virginia created the Richmond-Petersburg Turnpike Authority in the mid-1950s. The turnpike opened in July 1958 and later became part of I-95. Motels and tourist courts like the Robert E. Lee along Route1/Route 301 were bypassed and withered on the vine as the national lodging chains erected motels at the I-95 interchanges.

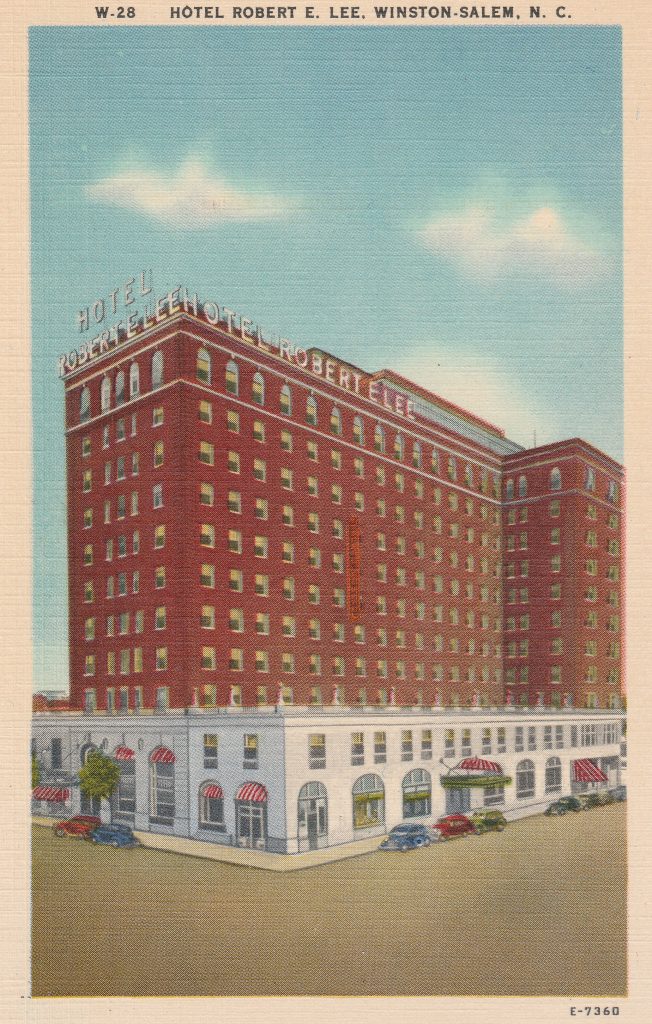

When it opened in 1921, the Robert E. Lee Hotel’s ten stories dominated the Winston-Salem, North Carolina, skyline. Winston Salem was a center of tobacco manufacturing, and the headquarters of the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. The Robert E. Lee Hotel had 550 rooms, all with private baths. Located on Fifth Street between Cherry and Marshall Streets, the hotel was the center of Winston-Salem social life. It closed in 1971 and was imploded on March 26, 1972. A Hyatt House Hotel opened on the site in 1974 and is now an Embassy Suites Hotel.

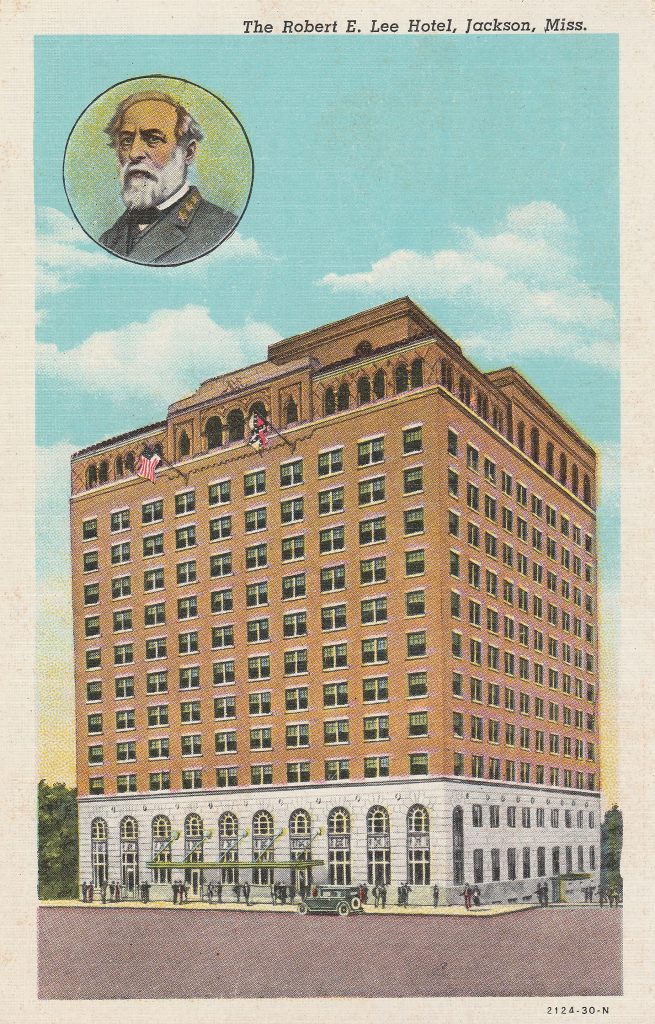

The Robert E. Lee Hotel in Jackson, Mississippi, opened in 1930. Located near the Mississippi State Capitol Building, the hotel had a steady stream of customers for three decades. Built in the Italian Renaissance Style, its lobby was richly decorated with marble and ornate column. The brass elevator doors had a portrait of General Lee and detailed scroll work. Guest rooms offered circulating ice water, ceiling fans (a necessity in humid Mississippi), and radios.

In the early 1960s, the Robert E. Lee was the third largest hotel in Jackson. On July 6, 1964. the hotel closed down rather than admit African American guests as required by the recently passed Civil Rights Act. No other hotel in Mississippi shut down. The owners declared bankruptcy in 1968 and the State of Mississippi acquired the building for office space in 1969. It was renovated in 1981 and 2011, but still retains the opulent lobby from its former days as a luxury hotel.

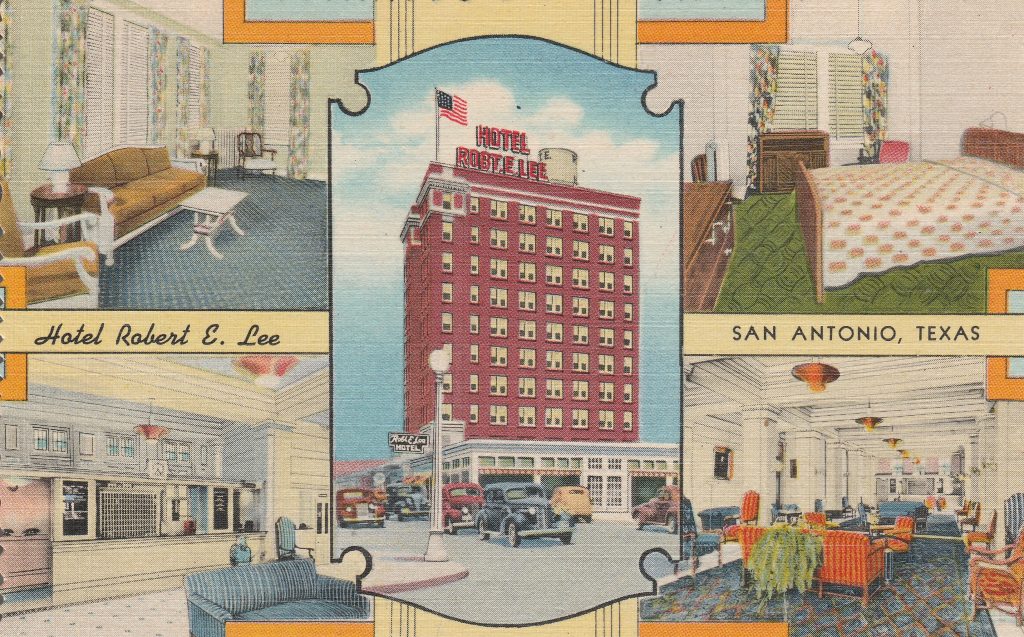

The ten story Hotel Robert E. Lee in San Antonio, Texas, was the tallest hotel in the city when completed in 1923. It was located on the Old Spanish Trail. Travelers, particularly businessmen, were offered 250 modern rooms with tub and shower as well as a garage, radio, and circulating ice water. There was a 225-seat coffee room, barber shop, beauty salon, and a cigar stand.

Advertising proclaimed the Hotel Robert E. Lee to be fireproof with fire hoses on every floor and a rooftop water tank. A newspaper advertisement of the era proclaimed the hotel would serve as, “a monument to San Antonio’s progressive spirit” and would solidify the city’s destiny “as the acknowledged metropolis of the Great Southwest.” The red neon sign on the roof was added in 1938 and is a San Antonio landmark.

By the mid-1940s, all rooms and public spaces were air conditioned, a necessity in humid Texas. The hotel prospered through the 1950s, but the hotel when into decline in the 1960s as newer hotels were constructed and the downtown business district decayed. Due to fire code violations, it was ordered closed by the city of San Antonio in 1976. It remained closed for nineteen years and was slated for demolition due to its deteriorated condition. Thanks to a federal grant of $1.2 million and a State of Texas grant of $2.7 million, the Hotel Robet E. Lee was saved from the wrecking ball and renovated into apartments in the mid-1990s.

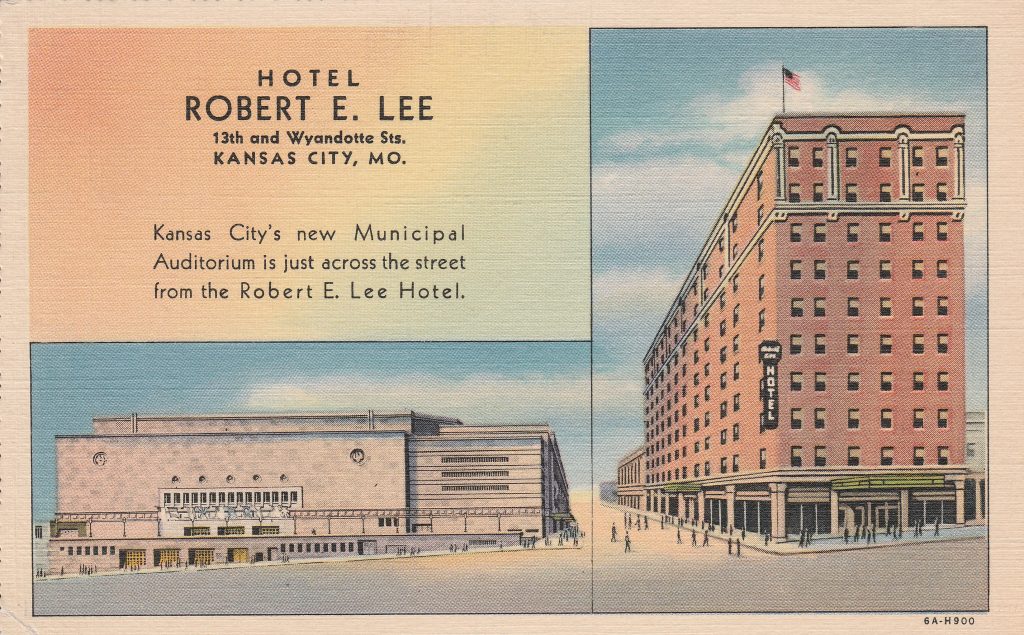

The Robert E. Lee Hotel was located on the northwest corner of 13th and Wyandotte Streets in Kansas City. It opened in November 1925 and was ten stories tall with two hundred rooms, each with a bath and ceiling fan. There were eight ground floor shops.

In 1935, Kansas City’s streamlined, art deco Municipal Auditorium opened across the street. Room rates in the 1930s began at $1.50 a day. During the early 1950s, the U.S. Air Force leased the hotel. The Robert E. Lee was demolished in 1954 to make way for a parking garage for the Municipal Auditorium,

**

Author’s Note: There were also hotels named for Robert E. Lee in St. Louis (later a Salvation Army lodging facility named the Railton Residence); Laredo, Texas, and in Athens, Tennessee.

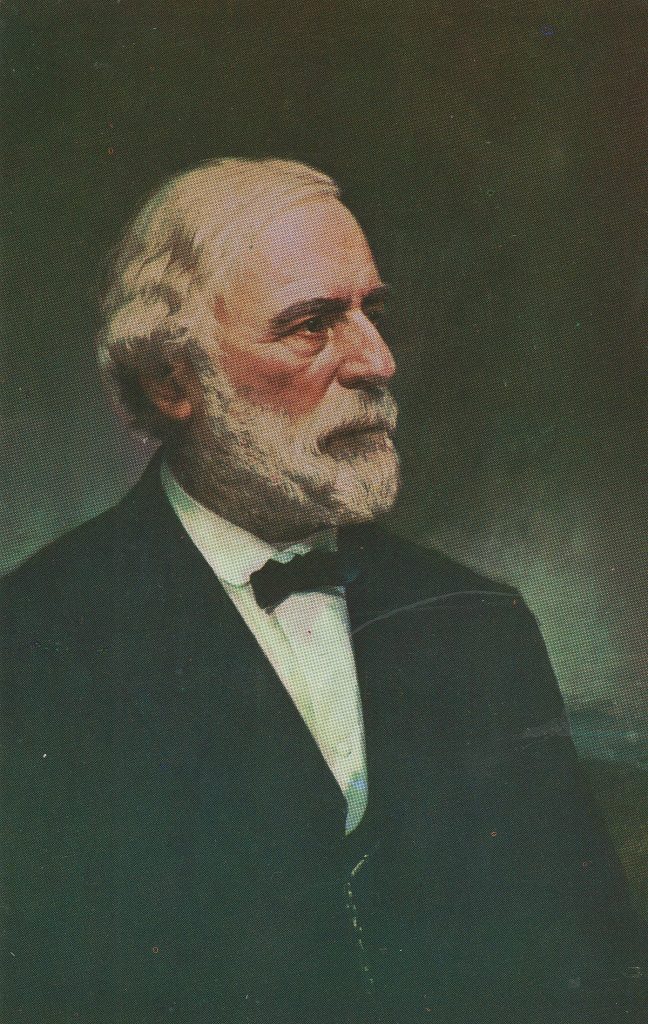

A portrait of Robert E. Lee by 19th century artist John Dabour depicting Lee as President of Washington College. It hangs in the University Chapel at Washington and Lee University. A copy is in the National Portrait Gallery.

___________

Robert E. Lee would have abhorred the cult of personality that started after his death in 1870 at the age of sixty-three. During the early days of the Civil War, he was not beloved by his troops who nicknamed him Granny Lee since they viewed him as too cautious in battle. (Only fifty-four when the Civil War began, Lee’s hair had already turned white.) They later called him the King of Spades after he had them dig defensive positions.

We will never know what Lee would think about the hotels and motels named in his honor. During the Civil War, he stayed in a tent with his troops, declining more comfortable lodgings. And, for a time in March 1863, Lee left his tent only after he suffered a myocardial infarction. Lee reluctantly followed the order of the physician attending him and recuperated in a house near where his troops were bivouacked.

This is a very interesting article. I have seen a lot of Robert E. Lee Hotel cards and have a few of my own; but, I never heard about the hotels’ declining years. The facts you mentioned regarding the General was also fascinating. Thank you for sharing the information.

Thank you for this interesting article!

Great article on the REL namesake hotels. The note regarding the cult of personality associated with Lee is interesting. If I recall correctly, the South did not think well of him immediately after the war. Let’s face it, he was the loser. The entire cult of personality exercise was a PR job by some of his underlings. I guess it was better to romanticize the “lost cause” than to admit you made a huge mistake by challenging the Union in the first place. The South’s miscalculation was similar to the one the Japanese made at the start of WWII. Transforming a… Read more »

Kevin you need to go back and study your hisory Gen Lee didn’t want to go to war.and he warned the south,unless everyone did there duties the south had no chance,If you knew your history you would know one of Gen Lee’s generals Lost Lee’s Marching orders .even then the.army of Northern Virginia with less than half the troops of the north, fought the battle to a draw with the north losing more men at Antietam.There are a lotta Liars and fools trying to rewrite history. You can’t change the facts Gen Lee and The Army of Northern Virginia was… Read more »

Thanks for the history of these hotels. Brought back memories of having to stop on I-95 to pay tolls at Richmond, VA back in the day.

When I was in elementary school, I came home with the exciting news that one of my friends, whose family had moved to Ohio from Mississippi, was descended from Robert E. Lee. My mother quickly explained that such a claim was put forth by many Southerners, and was not true in the vast majority of cases.

Thanks to Mr. Hennelly for an interesting article and thanks to Kevin for a most insightful comment.

Thanks for such such a great group of hotels, Mr. Hennelly! Now I’ll have to see what are in my collection!

Thanks for this fine history aeticle.

General Lee is Always my hero and the HERO OF THE SOUTHERN CONFEDERACY!!!