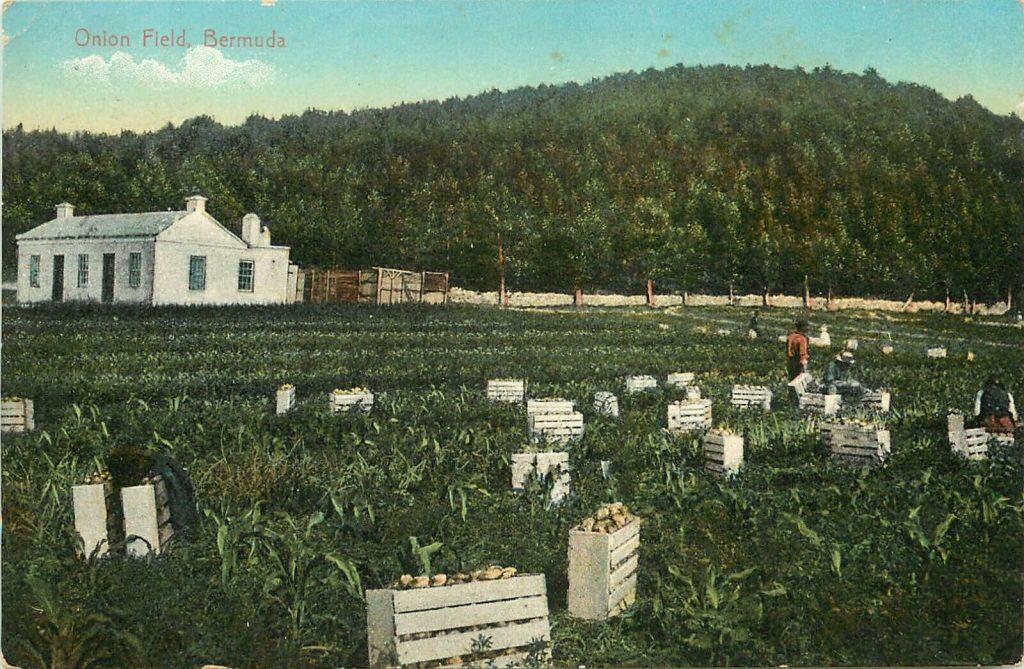

By the time Mark Twain made his second visit to Bermuda in 1877, he was able to write that “the onion is the pride and joy of Bermuda. It is her jewel, her gem of gems. In her conversation, her pulpit, her literature, it is her most frequent and eloquent figure. In Bermudian metaphor it stands for perfection—perfection absolute.”

Until the middle of the nineteenth century, Bermuda’s economy could fairly be described as little more than subsistence. The onion had come to the island in the 1600s but had not been much more than a local crop, barely registering as a blip on the export economy.

Things began to change with the 1850s arrival of skilled immigrants from Madeira and the Azores, who brought with them better farming techniques and better onion seeds. Their initiatives enhanced the development of the island’s agriculture industry into creating an exportable crop in the short period before the American Civil War.

With the onset of that war, Bermuda was blockaded, along with all the ports on the eastern coast of the southern states, because its government, along with the rest of the British Empire, openly sympathized with the Confederate cause.

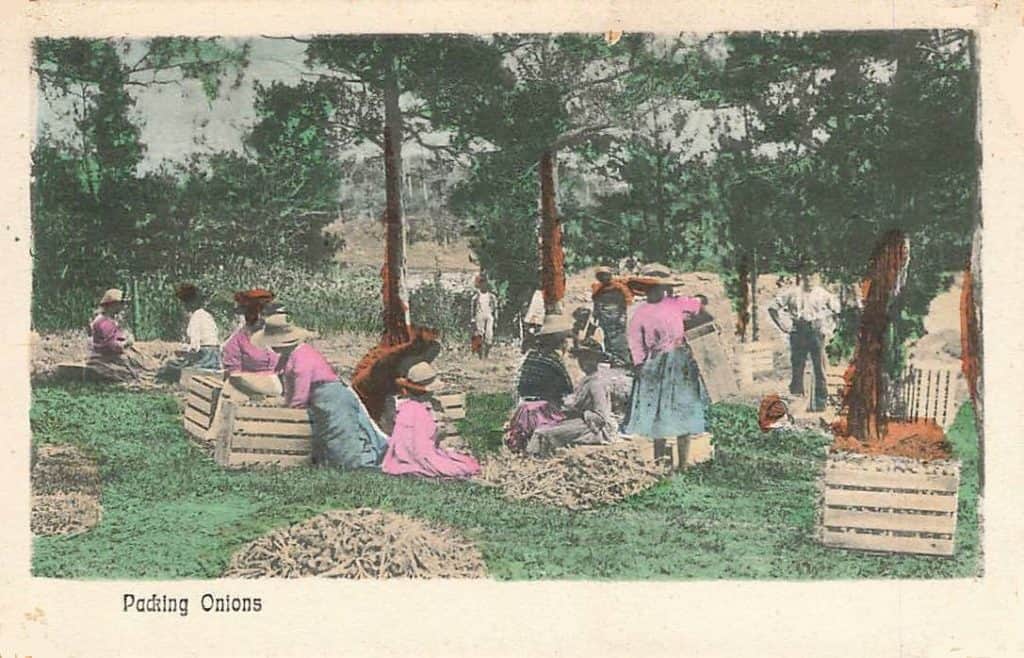

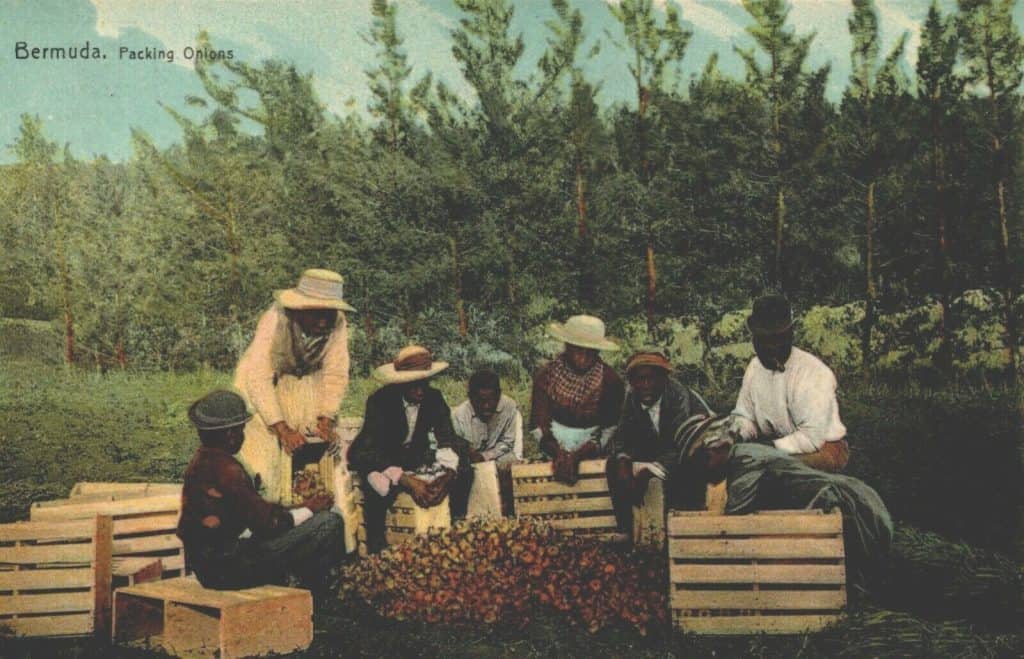

The blockade turned out to be a temporary blip in the onion trade. Hundreds of small farms began planting the onions that provided such an exportable crop that by the end of the nineteenth century they filled at least one ship making weekly trips to the American mainland with approximately 30,000 boxes of onions. By the onset of the First World War, one historian has reported that over 4,000 tons of onions were exported to the U. S.

The Great War delivered what in retrospect was a fatal blow to the island’s onion export business. The American economy turned to war production and prices for imported agricultural products increased with the imposition of substantial tariffs.

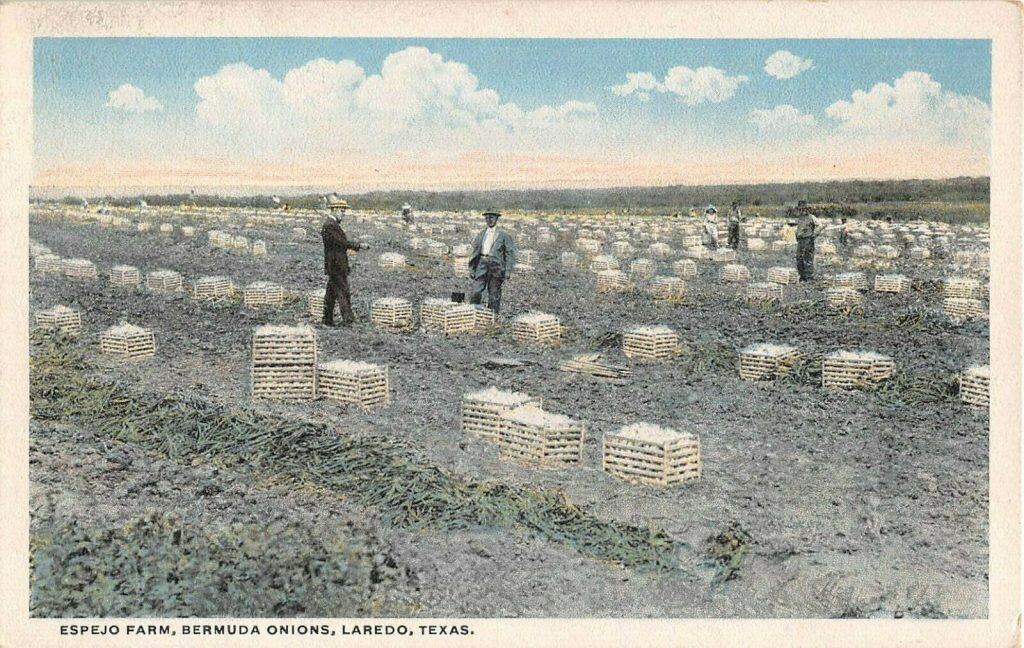

Farmers in the state of Texas filled the gap in onion production. Even before World War I these farmers had been growing and selling onions using seeds with origins similar to those used in Bermuda. The Texas climate, soil, and their freedom from tariffs made their onions more affordable than Bermuda’s. Railroad distribution was less expensive than ocean shipping, providing an overwhelming advantage not only to domestic distribution but also to exports. Bermudan farmers shipped over 150,000 crates of onions in 1914 but just 21,570 crates in 1923. It got to the point that Texas farmers were exporting over 1,000 railroad cars of onions alone to overseas countries.

Perhaps the icing on the cake was when a city named itself “Bermuda Colony” and later “Bermuda, Texas.” (It didn’t last beyond the 1920s as depressed prices for its onions and strawberries took their toll.)

The Bermuda Trade Development Board fought back in the 1930s, dispatching a postcard noting that its onions were unique as “It is the flavour of a genuine ‘Bermuda’ that is so different. Maybe it is the Sunshine and Sea Breezes down in beautiful Bermuda or some magic in the soil that is responsible, but whatever it is the flavour tells the difference immediately. Be careful then to always look for the crate… See that it is marked ‘from Bermuda Islands’ and you’ll know you are getting the real thing.”

It was no use. By the end of World War II, true Bermuda onions had disappeared from store shelves, never to return. And a new seed, Grano, replaced the original seed from the Canary Islands.

Bermuda today is a far different place than it was in the heyday of its onion production. No longer does Bermuda export agricultural products, instead it imports from the U.S., UK, Ireland, and other countries. Instead, its economy is based on tourism and corporate offices.

But once a year, on May 24th, Bermuda Heritage Day is celebrated with a live-streamed parade. It’s quite a sight.

Those are beautiful cards. It is amazing to how well they illustrate the Bermuda / onion history.

From being a stamp collector, I know that Bermuda is also famous for growing and exporting Easter lilies.

It is amazing how much one can learn from articles about postcards like this. If I could do it over I would use postcards as I used stamps for my students when I was a Rolling Reader here in San Diego. So now alongside exaggeration cards I’ll look for agriculture ones if I ever get to a card show again. Maybe I can talk with some of the NPCW people if I get better about e-mailing. Thanks!