General George Armstrong Custer, a flamboyant and controversial U.S. Army officer, became a legendary figure largely due to his role in the Battle of Little Bighorn. The Little Bighorn fight, on June 25, 1876, is one of the most famous clashes between the U.S. Army and Native American tribes. The battle resulted in a decisive defeat for Custer and his forces and marked a significant moment in the history of the American West.

Custer was born in 1839 in Ohio, he rose rapidly through military ranks during the American Civil War, earning a reputation for bravery and leadership. Some would say that he did so to the degree of being foolhardy. After the war, he became involved in campaigns against Native American tribes resisting U.S. expansion in the west. Custer was known for his aggressive tactics that might have been the reason he was assigned the tasks that made him famous.

***

In the 1870s, the circumstances between the U.S. government and Native tribes in the West, intensified as settlers and miners encroached on the lands on the Great Plains. The Sioux and Cheyenne tribes sought to defend their territory, which included the most abundant hunting grounds and their most sacred sites. The U.S. government, under pressure from settlers, sought to subjugate these tribes through military campaigns.

Late in 1875, while Ulysses S. Grant was in the final years of his presidency, gold was discovered in the Black Hills of the South Dakota Territory, on lands that were sacred to the Lakota Sioux. The news of such a discovery prompted a rush of prospectors. Consequently, Grant and his agents demanded the tribes relinquish their lands and relocate, but the tribes refused. Within a year, the conflict worsened and culminated in the Battle of Little Bighorn.

The Battle near the Little Bighorn River came to be known as Custer’s Last Stand, it took place in present-day Montana. Custer was in command of the 7th Cavalry Regiment, which played a large part in the government’s effort to force Native tribes onto reservations.

His pursuit of Native fighters led Custer to underestimate the strength in numbers of the enemy he was facing. His forces consisted of around 600 men that he divided into multiple units, aiming for a swift attack. However, his underestimations led to a disastrous end. Later historians have estimated that over 2,000 Native Americans, primarily Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho, had gathered in a large confederation led by leaders like Sitting Bull, Red Cloud, and Crazy Horse.

The Lakota Sioux and the Oglala Sioux were the dominant tribes involved, led by chiefs such as Sitting Bull and Red Cloud. Sitting Bull was a spiritual leader and played a significant role in unifying the tribes against U.S. expansion.

The Northern Cheyenne tribe, Lakota’s most reliable ally, was led by Chief Dull Knife, sometimes called Chief Morning Star. The eighteen-year-old Wooden Leg was a member of the Northern Cheyenne tribe; it is alleged that he alone killed more than ten of Custer’s men.

The Arapaho were also staunch allies of the Sioux and Cheyenne, because it was their land they were defending.

On a Sunday morning in June, Custer’s troops encountered the tribe’s encampment.

Custer ordered an attack and his forces had some initial success, but they were overwhelmed by a fierce counterattack, and shortly afterward, Custer and approximately 260 of his men were dead. The battle was short, but its consequences were very long lasting.

These tribes had come together in a rare moment of unity to resist U.S. military efforts. They were motivated by many good reasons, especially the threat of forced relocation to reservations. The defeat of Custer was a significant victory, but it was short-lived in the broader context. Soon after, the U.S. government intensified military campaigns, leading to the eventual suppression of Native resistance.

***

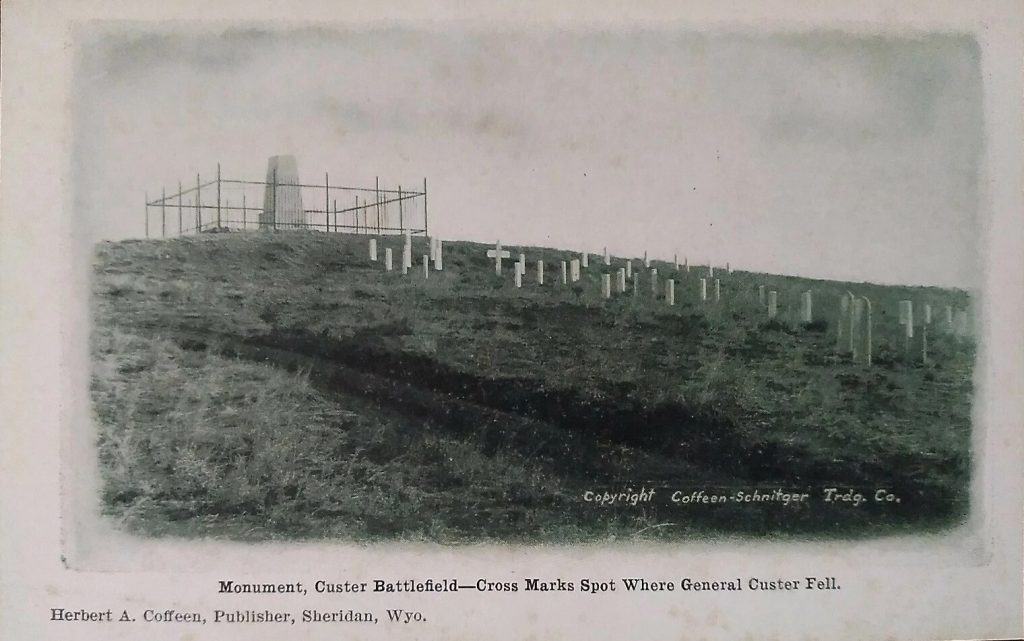

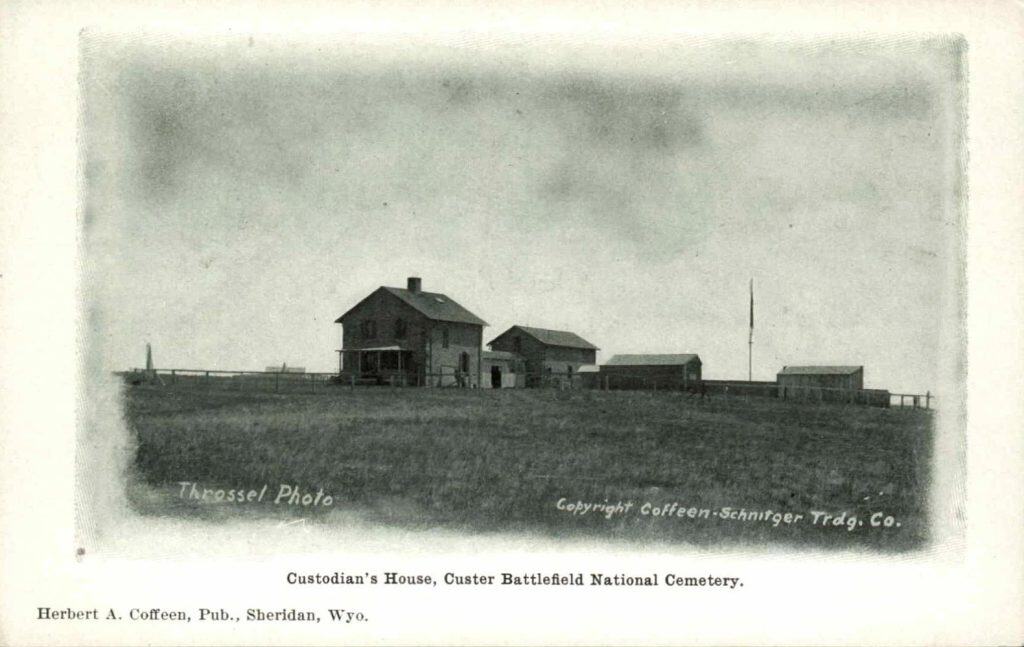

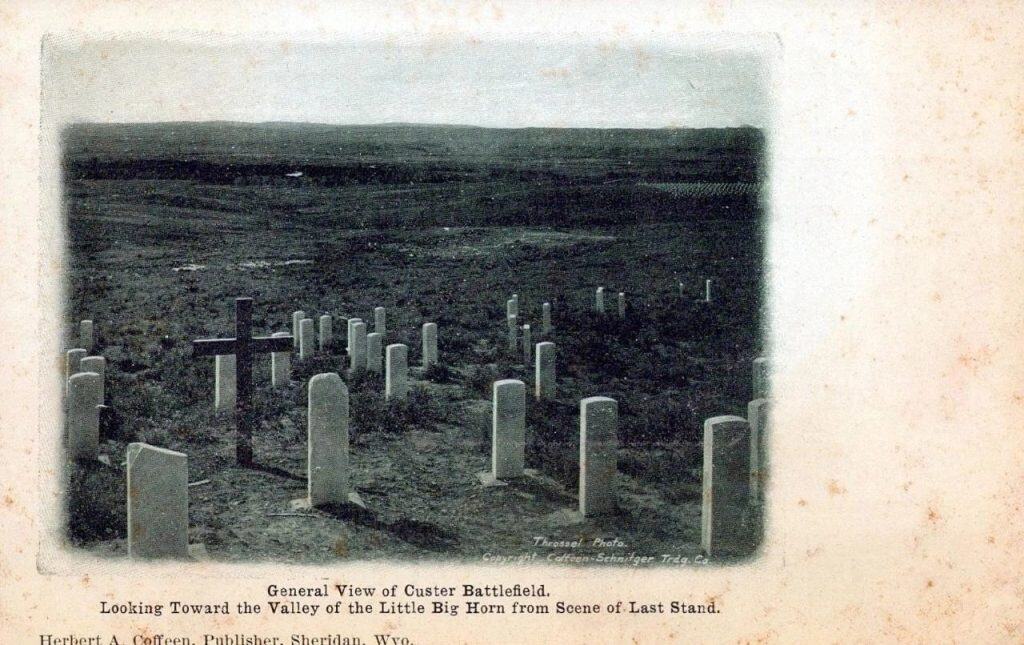

Coffeen and Schnitger Trading Company postcards. Apparently, there is no shortage of the Coffeen and Schnitger postcards showing the battlefield at Little Bighorn. They were issued either late in the nineteenth or early twentieth century. Each is easily identified since the known cards are in the same black and white format with a copyright scratched into the negative and an informational (or site) caption on an edge. Samples of these historical records may be seen here.

The caption on this card is contradicted by the National Park Service, the NPS’s official history of the battlefield suggests the date was 1879. Not “One Year Later.”