Pablo Picasso’s 1909 self‑portrait stands at the onset of a revolution: his own. 1909 was a time when the stirrings of Cubism began breaking the visible world into faces, angles, and shifting planes. Picasso’s earlier self‑portraits reflected the gravity of his Blue and Rose Periods, but this work marks a decisive turn toward a new visual language, one that would shortly reshape modern art.

Picasso’s self‑portraits mark milestones in his artistic evolution, each one revealing the mindset of what would come next.

This portrait offers a face that becomes his manner—solid, sculptural, almost carved from stone. The eyes are dark and searching and anchor the composition. This self-portrait is more of a declaration than a likeness. It is Picasso looking at Picasso and discovering someone entirely new.

Olga Khokhlova was Picasso’s first wife, a Ukrainian ballet dancer with the Ballets Russes, and one of his early muses, inspiring his neoclassical period after they met in 1917 and married in 1918; she was the mother of their son, Paulo, but their relationship deteriorated due to Picasso’s infidelities, though they never legally divorced.

Picasso’s Portrait of Olga captures a moment when devotion, discipline, and shifting artistic identity converged. Painted during the early 1920s, it reflects his turn toward a classic style he believed suited Olga.

The portrait’s refined outline and serene expression evoke the world of elegance Picasso tried to preserve even as modernism pressed him in many different directions. Though executed with traditional clarity the image stands as both homage and omen.

***

Museum postcards in today’s world are more souvenirs than vehicles for messages. They do however serve a valuable purpose – they introduce newcomers to art they would never see in its original format. And they help us learn! Here are some favorites.

***

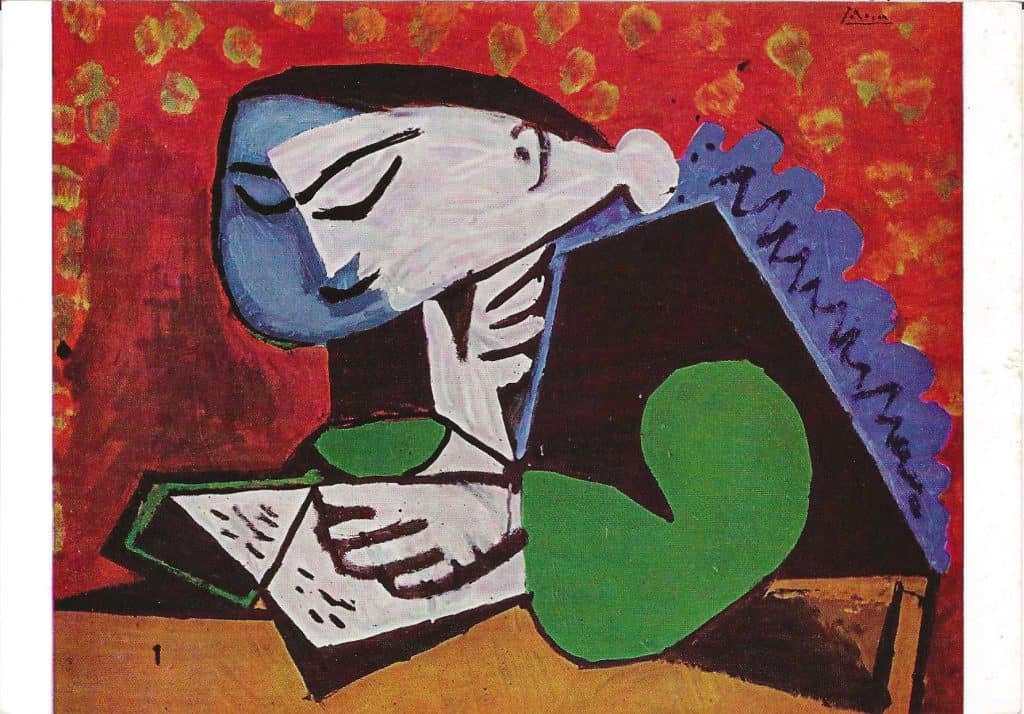

Girl Reading from 1938 is not a well-known piece, but it is my favorite of his portraits. It is a quiet meditation on solitude. Painted during a turbulent decade, it turns inward as it presents a young woman absorbed in a book, her posture curved into a private world of thought. The choice of color creates an atmosphere of hushed concentration. At the same time, Picasso was exploring bolder distortions elsewhere but here he favors gentler abstraction – simple forms, rounded contours, and a face rendered with calm, sculptural clarity. The result feels intimate. It is a portrait not of a specific person but of the act of reading.

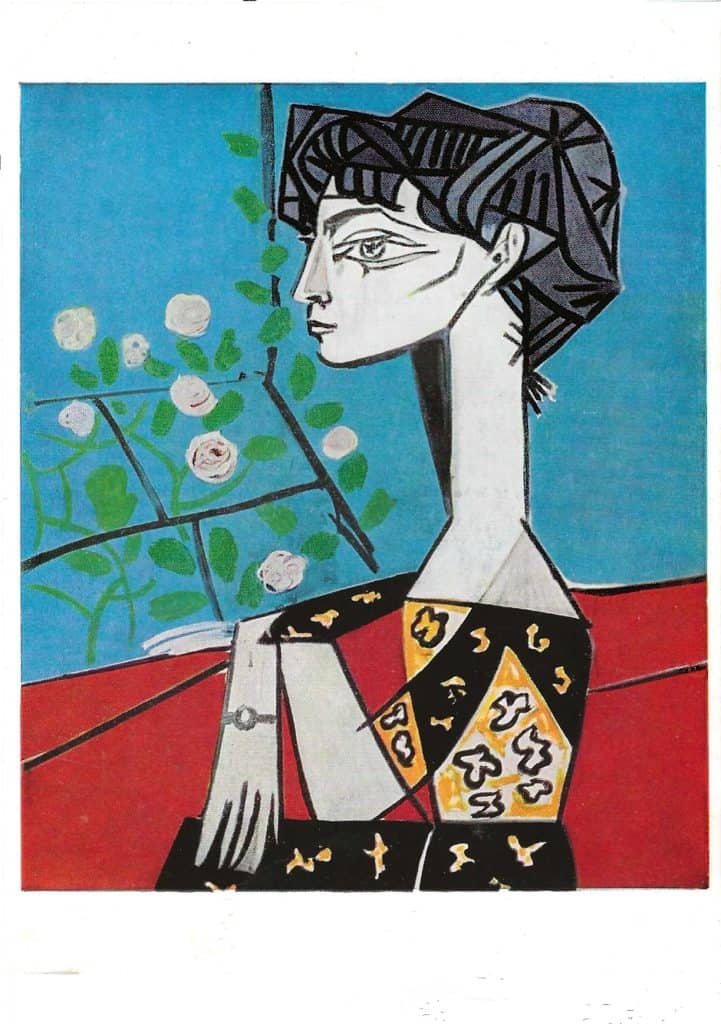

Picasso’s Portrait of Madame Z depicts Jacqueline Roque, the woman who became his final and most enduring muse. Created in the mid‑1950s, the image belongs to a period when Jacqueline’s presence reshaped his art, inspiring a new elegance and poise. In this portrait, her elongated neck, almond eyes, and composed posture convey both serenity and mystery, qualities that would define her many later depictions. The work marks the beginning of Jacqueline’s profound influence on Picasso’s late style.

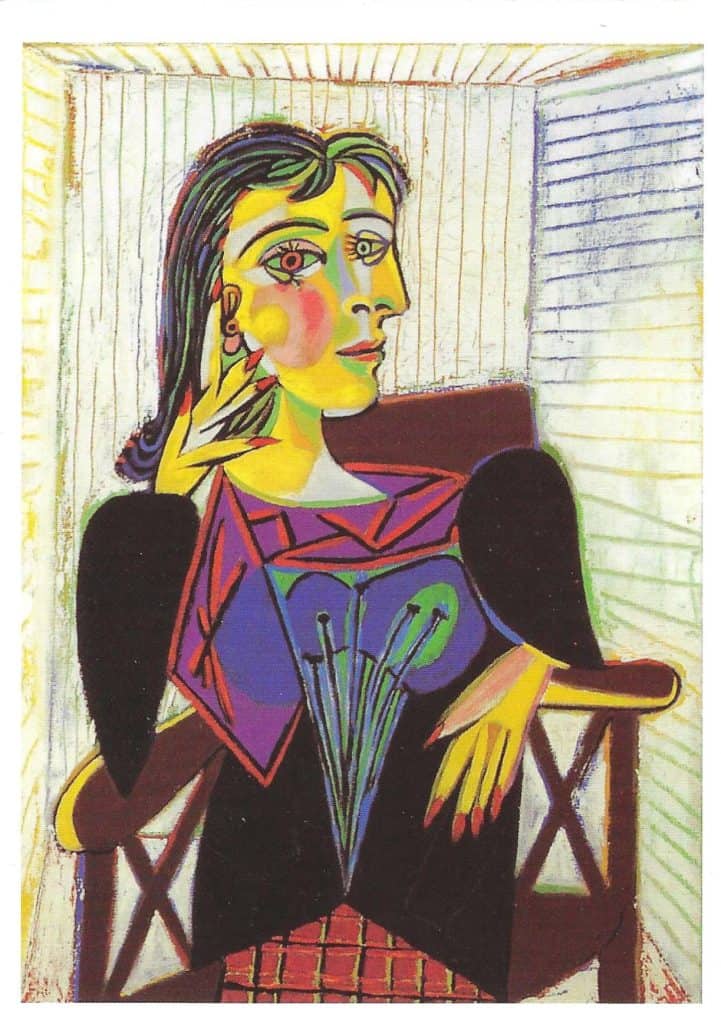

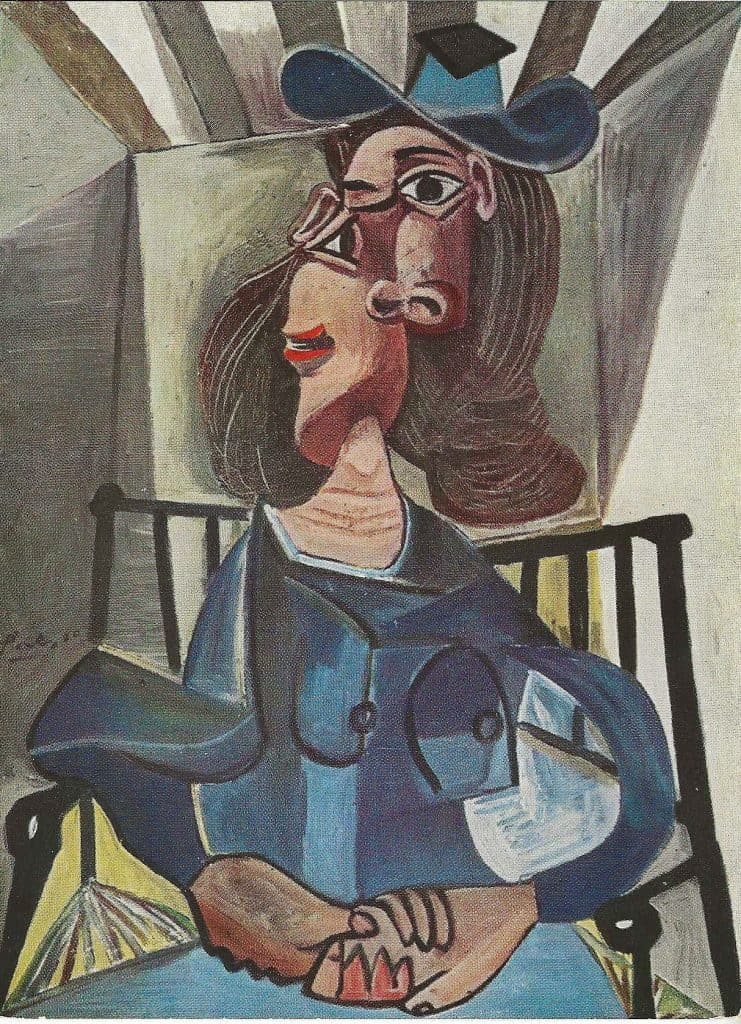

Picasso’s Portrait of Dora Maar (1937) captures the brilliance of his Surrealist muse, a photographer whose sharp mind matched his. Seated in an armchair, she appears fractured yet intensely present: a face split between profile and frontal view, one eye red, the other green. The distortions heighten her emotional complexity—poised, intelligent, and volatile beneath the surface. Painted at the height of their relationship, the work reflects both affection and tension, turning Dora into an emblem of Picasso’s most psychologically daring period.

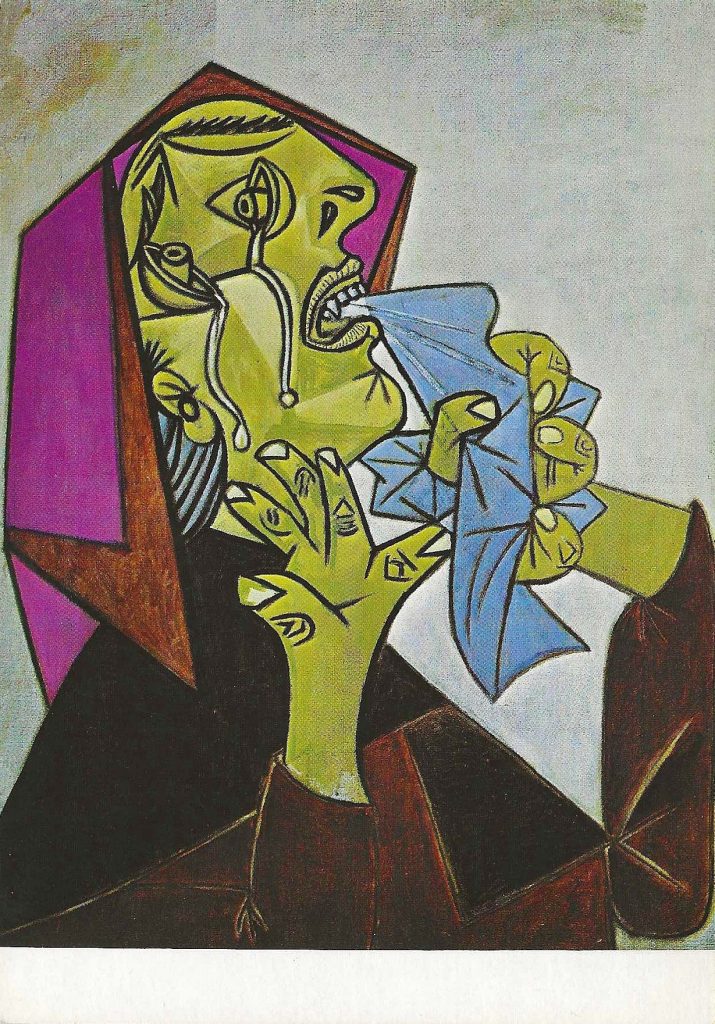

Picasso’s Weeping Woman with Handkerchief (1937) is a fierce meditation on anguish, created in the aftermath of the bombing at Guernica. The model is Dora Maar, his lover and a brilliant photographer, whose face becomes a fractured mask of grief. Sharp Cubist planes and jagged lines turn sorrow into something almost architectural. The clenched handkerchief is emblematic of chaos and pain.

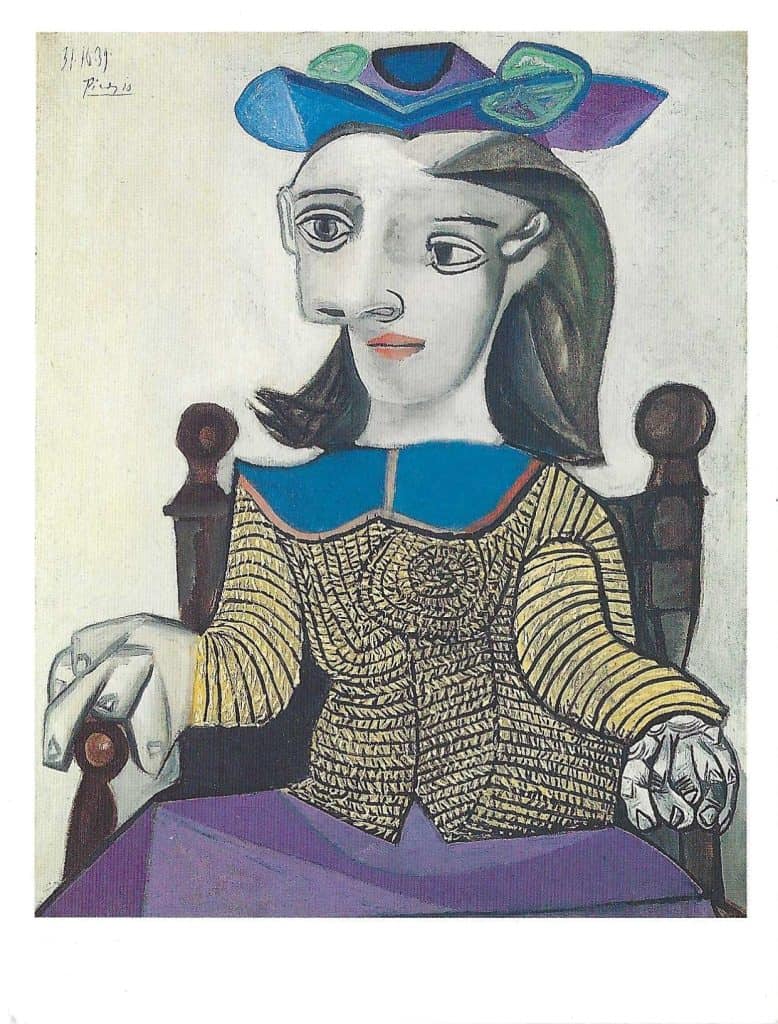

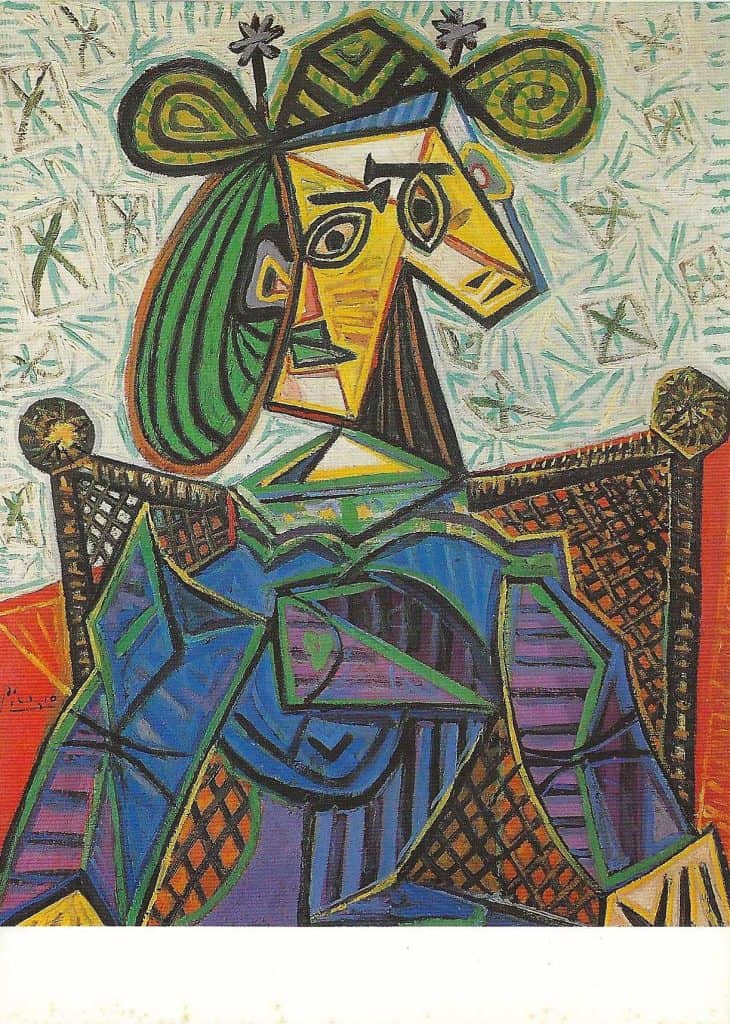

There are at least a dozen renderings of “Donna in poltrona” (Seated woman in armchair), the first painted in 1936 or 1937, the last in 1962. Seated Woman is a portrait of upheaval painted at the start of Picasso’s astonishingly productive 1937. This work shows a woman whose body becomes a stage of confusion. The palette is serene—blues and black polarized against each other to animate the figure. By having his subject seated he turns the armchair into a kind of psychological throne. This portrait belongs to the same creative storm that produced Guernica and you can almost feel the world breaking apart, and Picasso is reinventing how a human face can hold that fracture.

Woman in an Easy Chair is a work from 1941. The subject of the work is unknown, although the work was titled in German, Frau im Lehnstuhl, 1941, and it today is exhibited in the Kunstsammlung Nordrheim-Westfalen, Dusseldorf.

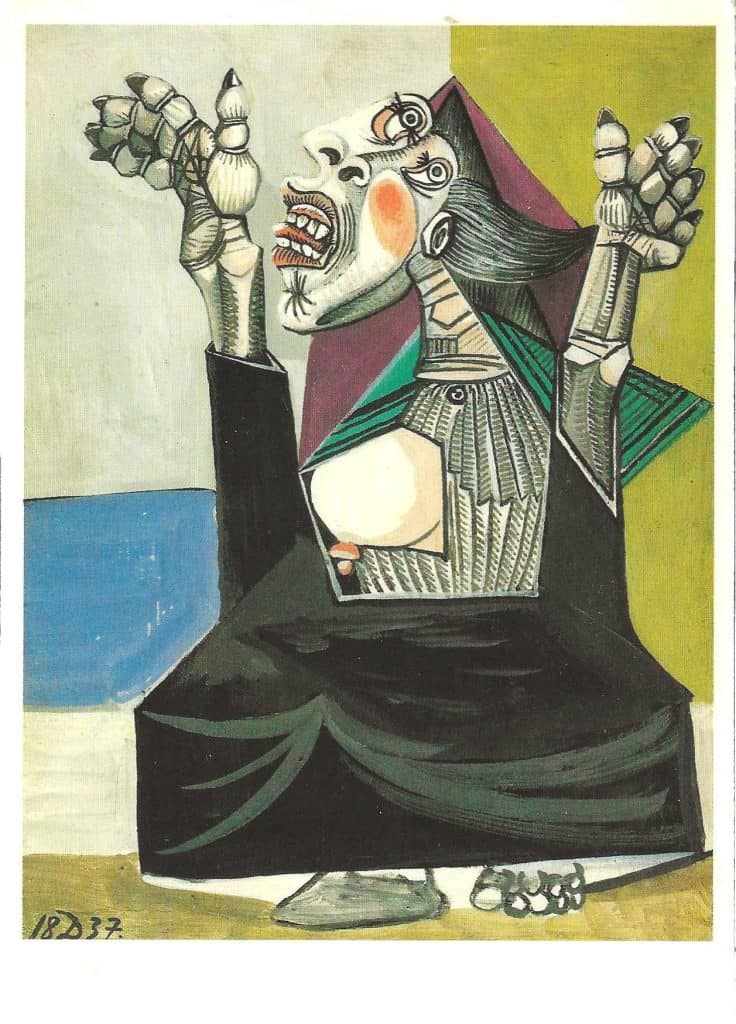

Picasso’s The Supplicant is a small but emotionally thunderous work. Created in December 1937, the same year as Guernica, it belongs to the same atmosphere of dread, violence, and moral outcry that shaped his art during the Spanish Civil War. The painting is a gouache on panel, just under ten inches tall, made in Paris.

Picasso’s Yellow Sweater is one of the most striking portraits he painted of his companion and muse, Dora Maar. It is a vivid, painting of Marr seated against a muted background, her body rendered in Picasso’s fractured, emotionally charged late‑1930s style. The yellow sweater is bold, warm, almost glowing is the emotional anchor of the composition.

Dora was a photographer, painter, and poet. Picasso’s portraits of her often spanned the emotions from admiration to unease. In this painting, she appears to exhibit both ends of that spectrum.

Painted the same year as works like Weeping Woman and Portrait of Dora Maar, this portrait belongs to a period when Picasso was responding to the Spanish Civil War. Dora, who documented the making of Guernica, was deeply tied to the same political and artistic movement. Why does it matter? Because this painting is a quiet equivalent to Picasso’s more anguished Maar portraits. The yellow sweater becomes a kind of armor, a soft shield against the fractured world of Pablo Picasso.

Exploring the portraits of women created by Pablo Picasso in the late 1930s through museum postcards gives us a fascinating look at a crucial time in the artist’s development and the wider cultural scene. In this era, Picasso’s art went beyond just showing things as they are, mixing his unique Cubist style with deep emotions and complex symbols. The women he painted are not just simple figures; they represent strength, vulnerability, and a rich identity, often mirroring the chaotic social and political atmosphere of Europe before the war. To appreciate these portraits today is to acknowledge Picasso’s incredible skill in… Read more »

Very interesting Some I knew and some we are new to m Thank youj

Again showing how postcards offer insights into worlds beyond our usual. I have never enjoyed Picasso, but this article shows that I may have been missing something. Thank you.