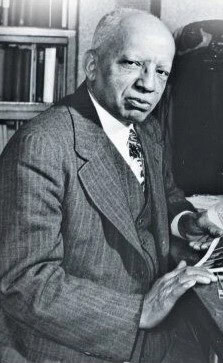

Carter G. Woodson once stood as an influential scholar of American history; someone whose determination reshaped how our nation valued its past. Woodson devoted his life to correcting the erasure of African American experiences from the mainstream history books. For Mr. Woodson, the work he did was not an academic exercise, it was a mission to restore dignity and accuracy to a people whose contributions had long been ignored.

Born in 1875, Woodson was the son of formerly enslaved parents in Virginia. He grew up with limited access to formal education, yet he managed to find alternate sources for the knowledge he wanted. After years of self‑education and labor in West Virginia coal mines, he eventually earned degrees from Berea College (Berea, Kentucky), the University of Chicago, and ultimately a PhD in history from Harvard University (he was only the second African American to earn such a degree.)

This achievement alone marked him as a trailblazer, but Woodson saw scholarship as a tool for liberation, not personal prestige. He recognized a profound problem in American historiography: African Americans were either misrepresented or omitted entirely.

Woodson believed that anyone deprived of knowledge about their past would struggle to understand their present and were hindered from shaping a future. With that in mind he founded, in 1915, the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in Washington, D. C.

His organization became the institutional backbone of his efforts. It supported research of every kind, made publications possible, and encouraged educational programs in school systems across the nation.

In 1916, Woodson launched The Journal of Negro History (now The Journal of African American History). The groundbreaking publication provided a platform for verifying black achievements, analyzing the effects of slavery and racism, and preserving cultural traditions. At a time when mainstream journals refused to publish such work, Woodson created this space where rigorous research on African American life could flourish.

Perhaps Woodson’s most widely recognized contribution was the creation of Negro History Week in 1926. He strategically chose February to coincide with the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln, two figures deeply connected to emancipation. What began as a week of celebration and education eventually expanded into Black History Month.

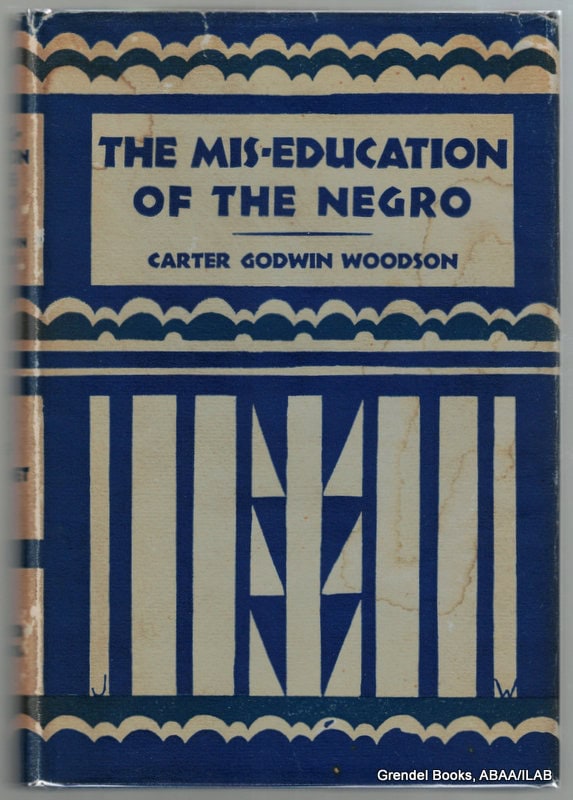

Woodson’s scholarship extended beyond leadership. His book, The Mis-Education of the Negro, (1933) challenged systems that denied black Americans access to accurate historical knowledge and denounced the “Euro-centric” school curricula.

Woodson inspired black Americans to demand relevant learning opportunities that were inclusive of their own culture and heritage. In issuing this challenge, he laid the foundation for more progressive and equal educational institutions.

He argued that education must empower rather than marginalize, and he urged African Americans to reclaim their heritage as a source of strength.

Carter G. Woodson’s legacy endures because he fundamentally changed the way history was written and taught. His insistence that American history without African American representation is just biography. Woodson proved that history is more than a record of the past, it is a tool for shaping the future.

***

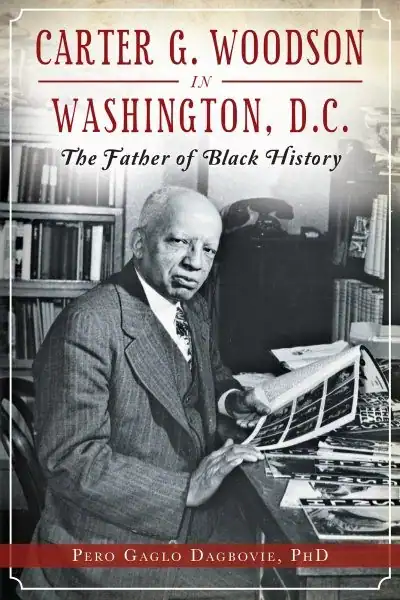

A comprehensive retelling of Woodson’s work in Washington, D.C. appeared in late 2014. The author, Dr. Pero Gaglo Dagbovie is a renowned scholar who, like Woodson, has devoted much of his career to writing about the black experience in America.

Thank you!

Send this to the President. His knowledge of history is abysmal

I am ashamed to say that I never heard of Carter Woodson, so I truly appreciate finding out about his efforts to incorporate African America’s accomplishments into our history.

Thank you for publishing this article and introducing this gentleman. America History needs to be covered – warts & all. – is my belief. Without covering it – warts & all – Am. history is lopsided and students of it are lopsided in their knowledge.