Benjamin H. Trask

Coastal Sentinels:

United States Lighthouses

A thread of shoreline with a lighthouse has long been a focal point for artists and photographers as well as a destination for tourists and lovers. At the close of the postcard’s golden era, around the outbreak of World War I, America boasted more than 1,400 lighthouses tended by resident keepers. With the introduction of various means of automation, however, the number of inhabited stations declined as the twentieth century progressed.

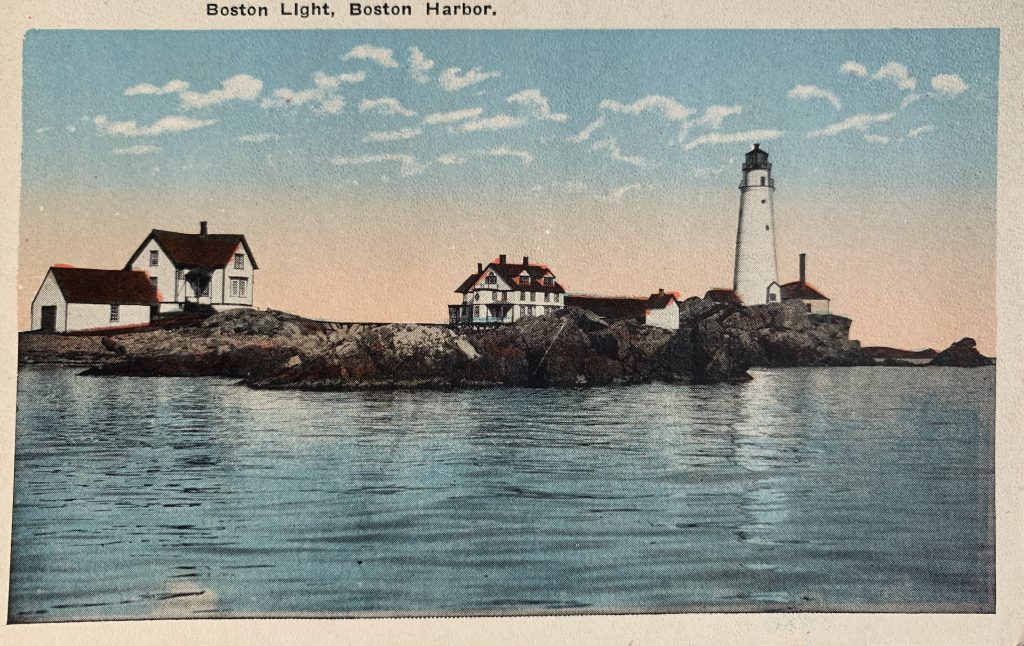

Colonial Era Lighthouses: Structures such as Sandy Hook (1764) in New Jersey; Beavertail (1749) in Rhode Island; and Boston Light/Brewster Island (1716, rebuilt 1783) in Massachusetts were constructed by colonial governments to promote secure trade. Following the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, the federal government assumed control of the lighthouses. Today, the Coast Guard Auxiliary tends to the Boston Light; a nod to the island’s status as the first light.

Cape Henry Lighthouses: In the 1790s, the United States government began building its first tower on Cape Henry in Virginia. Ninety years later, structural concerns and the desire for a more powerful light led to the construction of a second Cape Henry beacon. In 1983, the Coast Guard automated the second Cape Henry Lighthouse. Today, the first United States light rests within the boundaries of Fort Story, near Virginia Beach, and is owned by Preservation Virginia. Simultaneously, the second tower invites maritime traffic into the sheltering waters of the Chesapeake Bay.

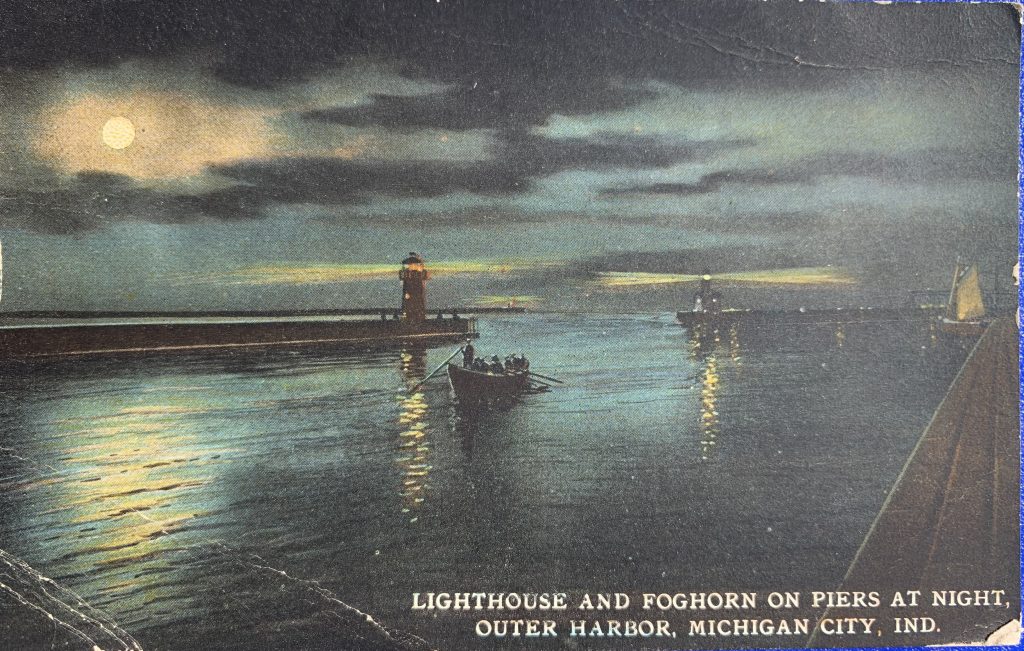

Indiana Lighthouses: More than thirty states can claim lighthouses within their borders. And while not thought of as a coastline for lighthouses, the Hoosier State boasted numerous stations along Lake Michigan. Among the stations is the Michigan City East Light.

United States Lighthouses Overseas: In the late 1800s, United States expansion sparked the need to provide overseas navigation aids and keepers. These island territories and possessions included Puerto Rico, Guam and American Samoa. Likewise, the environs of the Diamond Head Light on O’ahu, Hawai’i features volcanic cone, a life-threatening reef and the beautiful Waikiki Beach.

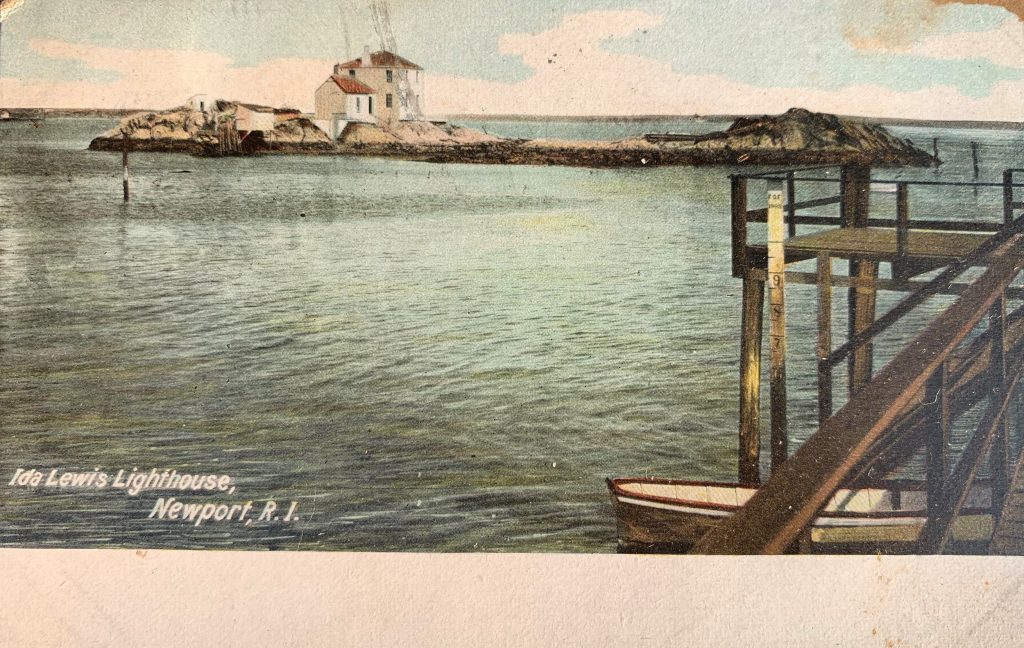

Ida Lewis and Women Lighthouse Keepers: Of the hundreds of American women keepers and assistant keepers, Ida Lewis (Idawalley Zorrada Lewis) was the most famous. This keeper’s daughter, tended Lime Rock Light, unofficially and officially, for more than forty years. When President Ulysses S. Grant sought to meet Lewis, she would not leave her post. So respectfully, the president made the journey to Rhode Island. Frequently decorated for her heroic exploits during her lifetime, the lighthouse was renamed in her honor. This gesture was a unique nod of respect for a keeper. Adding to her honors, the Coast Guard named the lead vessel in the Keeper-class of cutters, USCGC Ida Lewis (WLM-551).

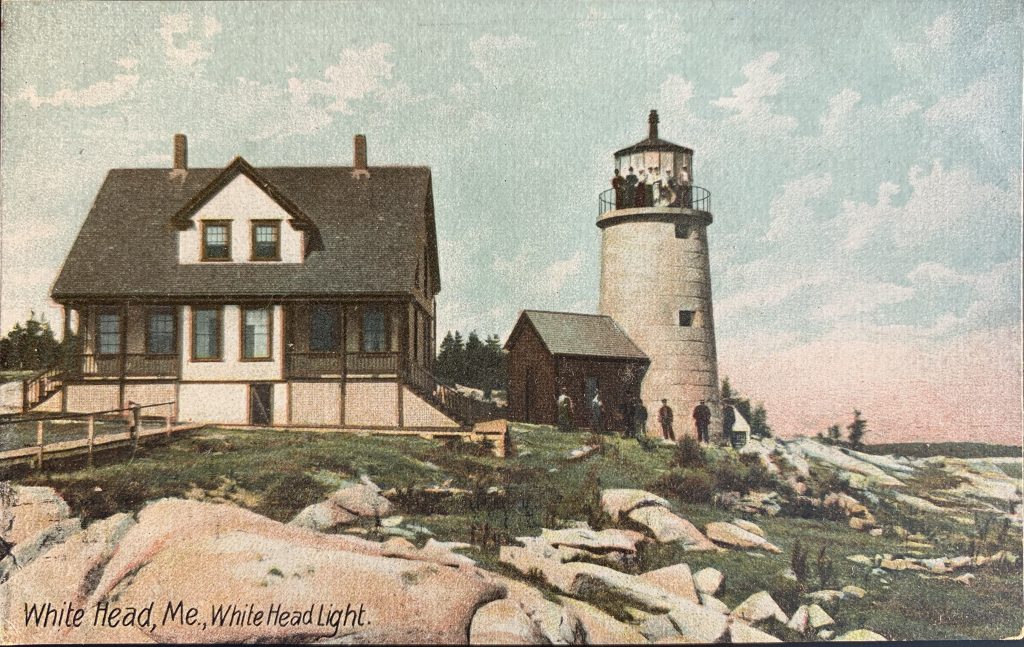

Lighthouse Visitors: Whether it was the enticing setting or the keeper’s exploits, light stations have long been traveling destinations. In one season, nine thousand visitors came to see Ida Lewis and Lime Rock Lighthouse. This popularity required keepers to spend much of the working day as guides while still fulfilling their duties in the evening. Lighthouse keeper’s daughter, Abbie Burgess (later Grant) became a notable figure for attending the Matinicus Rock Light during a raging storm. Later, she and her husband were the keepers at Whitehead Light.

Other-worldly Visitors, or Strange Tales at Lighthouses: Eric Jay Dolin remarked in his recent lighthouse history, Brilliant Beacons: “Each year millions of people visit America’s lighthouses … some even come for the ghosts. It seems that nearly every lighthouse has a ghost who makes an appearance from time to time.” The emergence of these eerie settings in local lore and literature is not a recent trend. Before his death in 1849, Edgar Allen Poe, left four pages of an unfinished yarn that had the keeper enamored by a life of solitude.

One of the stations in a shroud of unnerving tales is Owl’s Head Light in Maine. The name alone sets the stage for the “creeps.” The related stories feature the spirit of a former keeper, a misty female resident and unexplained activity in the kitchen.

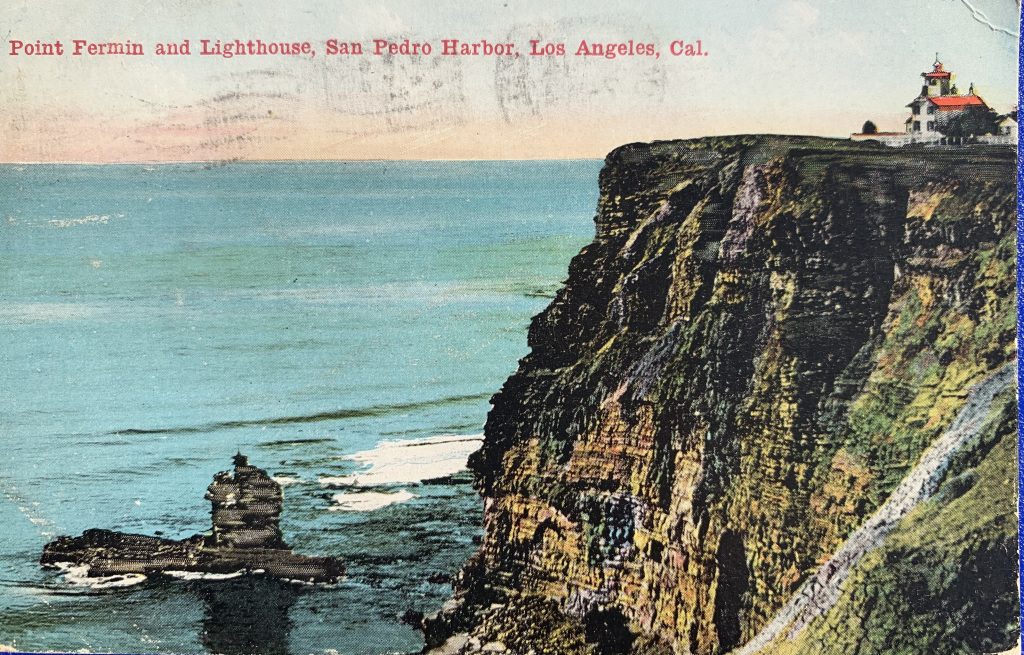

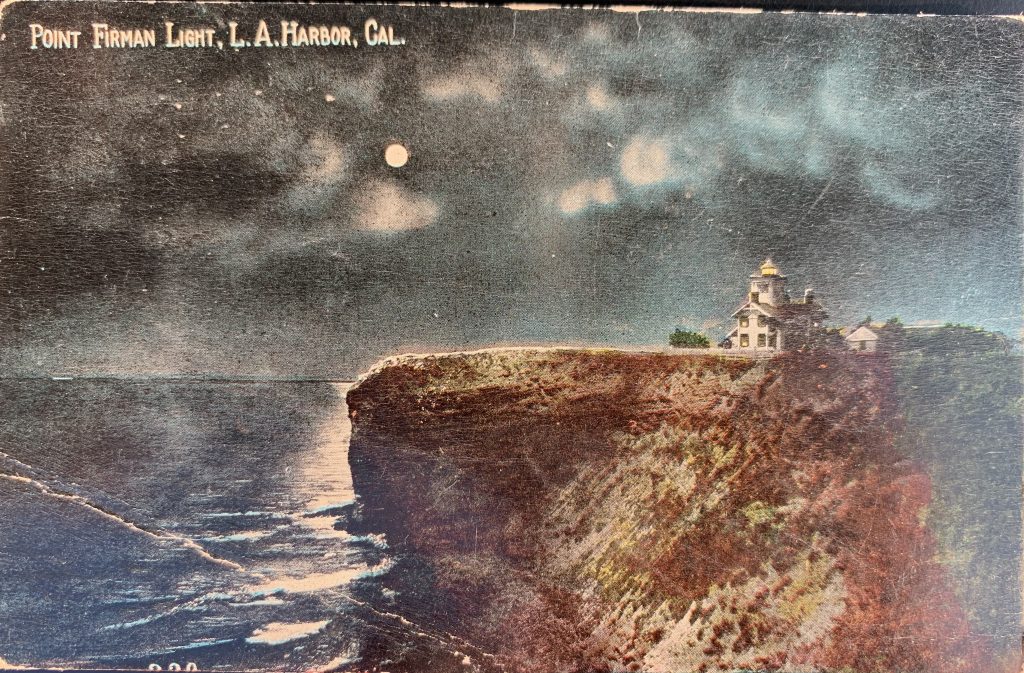

Point Fermin Lighthouse: Overlooking the cliffs of San Pedro Harbor, California, this gingerbread-cottage lighthouse is another station that whispers like a gothic novel. From 1874, women often operated the scenic station. In fact, two pairs of sisters cared for the beacon. Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the lighthouse was darkened for fear of being an attraction for Japanese submarines. A chicken coop replaced the lantern room. In 1970s, supporters restored the lantern room and dignity to the structure. It is now an historic site and museum.

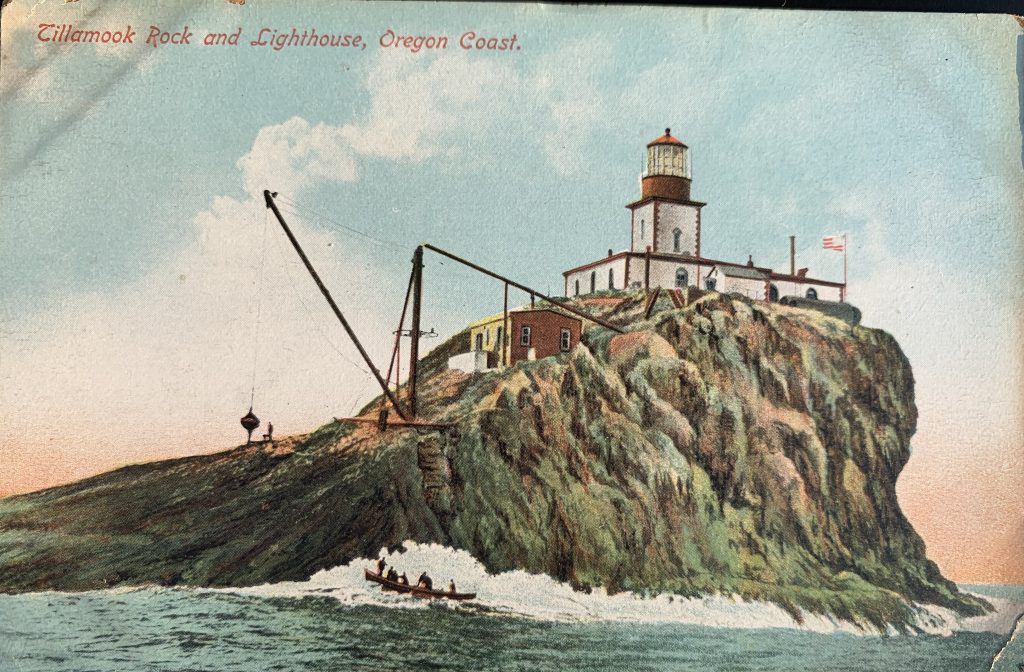

Engineering Challenges—Tillamook Rock Light: Focus beyond the lighthouse scenery to image the creativity, engineering skills and determination to construct towers in harrowing locations. One of the best examples of this type of challenge was the Tillamook Lighthouse or “Terrible Tilly,” a little over a mile off of Oregon’s northwest coast. During the long construction project at least one surveyor lost his life and a sailing bark wrecked nearby with the loss of all sixteen crewmembers. Just getting keepers to the rock was an undertaking. Staff spent a shortened shift on the rock because of having to endure the inclement weather. In 1957, the light’s function was replaced by a buoy. The station later became a columbarium with about thirty funereal urns, an operation that lasted about twenty years.

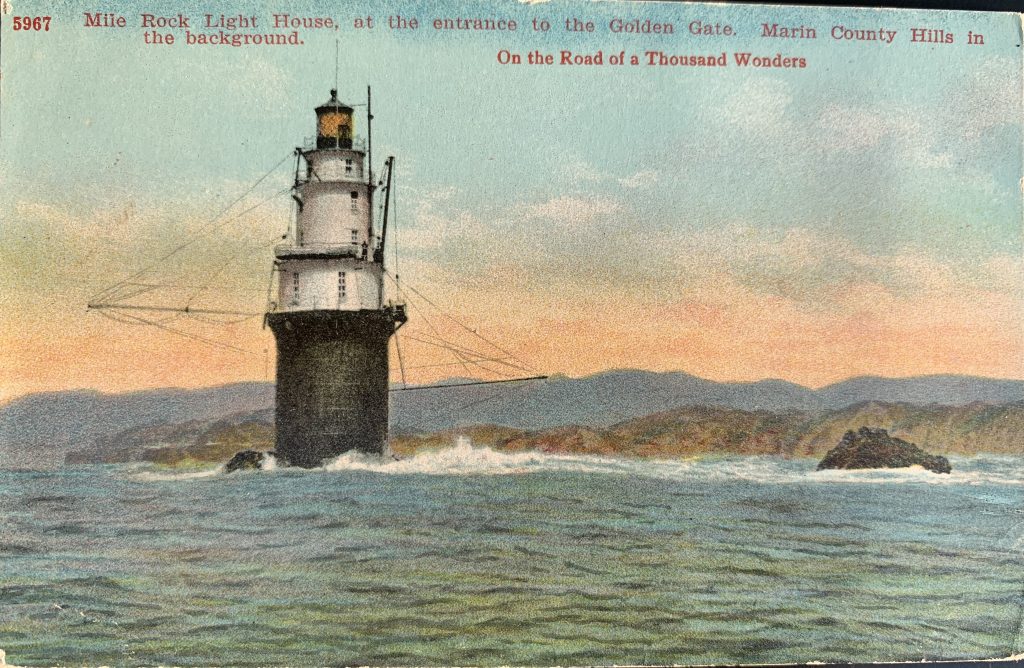

Iron Caisson Construction: The caisson-style lighthouses first appeared in the United States in 1871, with the construction of the Duxbury Pier Lighthouse in Massachusetts. This sturdy design, such as Mile Rocks Light off Lands End, San Francisco could withstand storms, ice floes and swift currents. The caissons were huge cylinders that rested vertically in a wooden frame on a shoal or island. This lighthouse style was thought to resemble a teapot or spark plug.

Skeleton Tower Design: Climate and geography dictated lighthouse design. Screw pile lighthouse featured massive iron augers or screws fixed in the shallows with an inviting, wooden lighthouse atop. This style of station was prominent in the Chesapeake Bay. Often it was the staff of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers which tackled design challenges. One of those undertakings resulted in skeleton towers anchored by screw piles. These beacons appeared along the Gulf of Mexico and Florida’s eastern coast. The framework allowed the movement of hurricane force winds without damaging the structure.

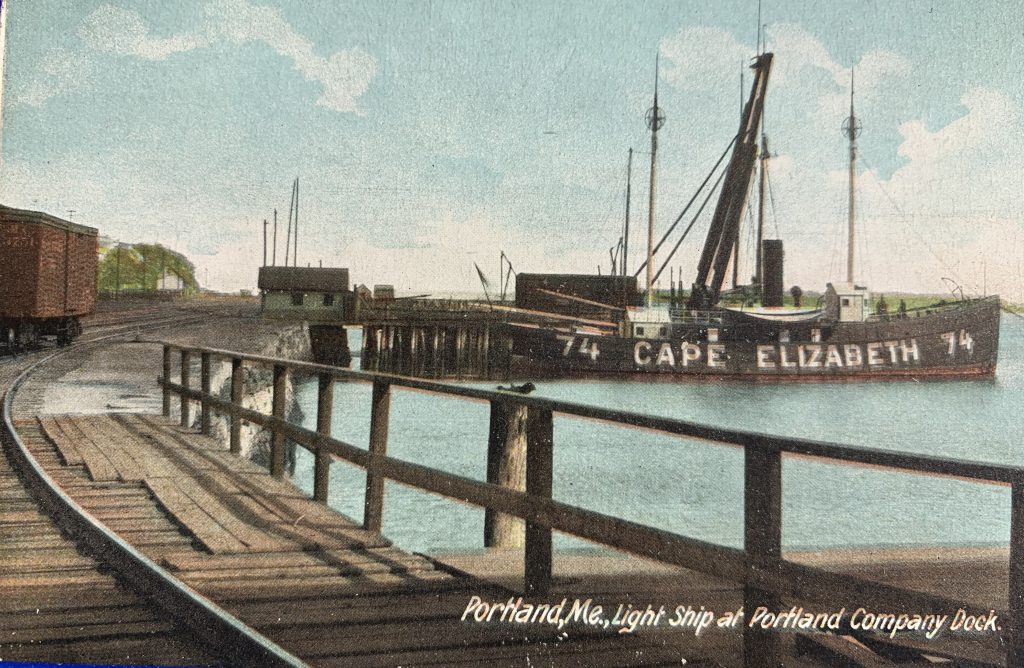

Lightships: The year 1820, welcomed the first United States lightship. At a fixed anchorage, these vessels with a unique light signature on the mast became a flexible means to protect shipping. Assisting navigation to Portland, Maine, LV-74 was one of the last wooden-hulled lightships built in the United States. For a more detailed look at these floating signals see the Postcard History article, “Lightships” (January 6, 2020).

“I Love You” Light: The flashing 1-4-3 pattern of the Minot Ledge Light near Cohasset, Massachusetts corresponded with the number of letters in the pronouncement: “I love you.” For that reason, the blessing from the light’s glow has been a favorite for couples. This is a far cry from the original construction efforts at the Ledge that ended in 1855, when the defective lighthouse crashed into the sea and consumed the lives of the keepers.

African American Keepers: Following the Civil War, dozens of African American men served as lighthouse keepers in the Southeast. John B. “Jack” Jones, a former slave, served one of the longest and most notable tenures (1878-1907) at the Old Point Comfort Lighthouse on Fort Monroe. In an epoch that required intense political jockeying to hold government positions, Jones managed to maintain his post for almost thirty years. His obituary in the Daily Press noted he had amassed a fortune of $25,000 and “was widely known in Tidewater Virginia.” Following Jones’s death in 1907, his son, Warren Wright Jones briefly tended the light.

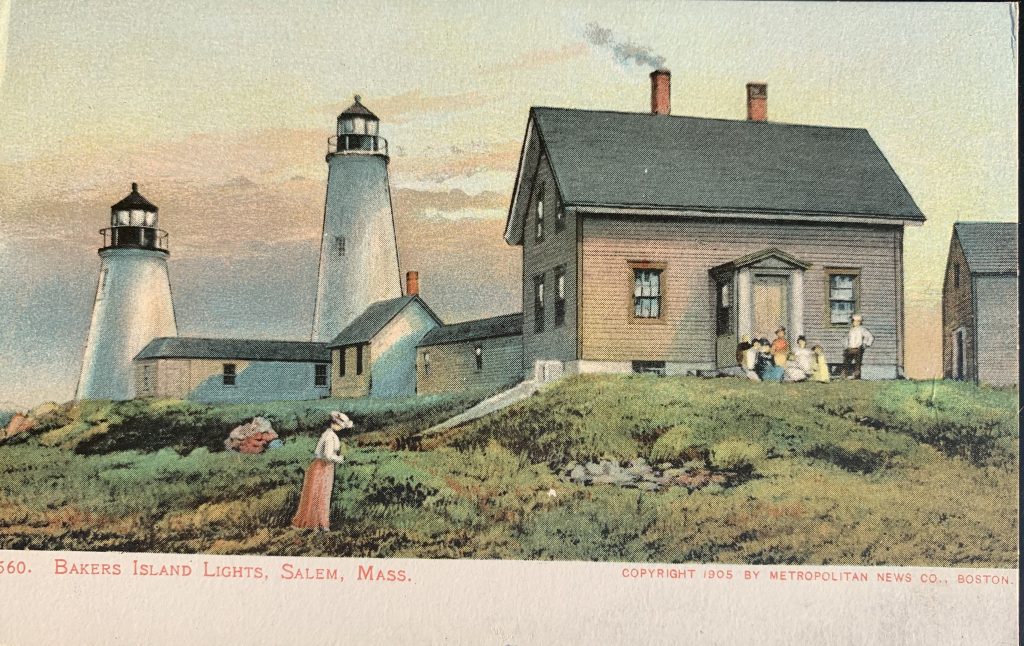

Communities of Keepers: Keepers and their spouses reared large families. These children, such as the aforementioned Ida Lewis and Abbie Burgess Grant, often joined and/or married into the Lighthouse Service. This is mentioned frequently in lighthouse histories. Norman Rockwell captured this kinship bond between generations in his painting the “Lighthouse Keeper’s Daughter.” The people in the postcard at the tandem of Bakers Island Lights in Massachusetts (known unofficially as Ma and Pa) may represent one of these families.

Not part of the discussion on keepers are the communities of “wickies” with their complex familiar and fellowship ties. Two of these maritime enclaves were the keepers of Mathews County, Virginia on the Chesapeake Bay and North Carolina’s Outer Banks. Their collective nautical skillset allowed them to serve on lighthouse tenders, lightships and more than fifty lighthouses in the Fifth District.

Great story. Love visiting lighthouses, variety of designs fascinating.

One of my favorite books during my childhood was “The Little Red Lighthouse and the Great Gray Bridge”, set around New York City’s George Washington Bridge.

Greetings Bob,

I have the same great memory.

Benn Trask

Am learning so much from “Postcard History” site ! I love postcards, but am beginning to think I need to save only a select few boxes. Who should I talk to about selling ? As you may notice this problem is keeping me awake at night. Thanks for contacting me.

Send email to Postcard History’s editor@postcardhistory.net. Explain what you are trying to do and ask your questions. We will find answers for you.