Hy Mariampolski

Nights in Harlem

In the years following World War I, Harlem an area stretching from the North of Central Park to the curving shore of the Harlem River, became New York’s preeminent African American Community. It had some special areas like “Sugar Hill” north of City College, “Striver’s Row” on 138th and 139th Streets and Mount Morris Park. But, to most people, it was all Harlem or “Uptown.”

The movement of African Americans into Harlem in the years after World War I followed what has been called the “Great Migration” of Blacks from the Southern states that comprised the Old Confederacy and the West Indies to major Northeastern and Midwestern cities. While in 1920, central Harlem’s proportion of Black residents had grown to 32.43%, by the 1930 census fully 70.18% of central Harlem’s residents were black.

Wishing to escape violence and discrimination in the South and seeking employment and educational opportunities in the North, the migration was not only a movement of population but also represented a major shift in the intellectual and cultural status of African Americans. The surging numbers coincided with the social movement that has come to be called the “Harlem Renaissance.” This framework of ideas involved a new militancy in the civil rights struggle as well as an affirmation of independence and new cultural visions and expressions, including literature, art, drama and especially music.

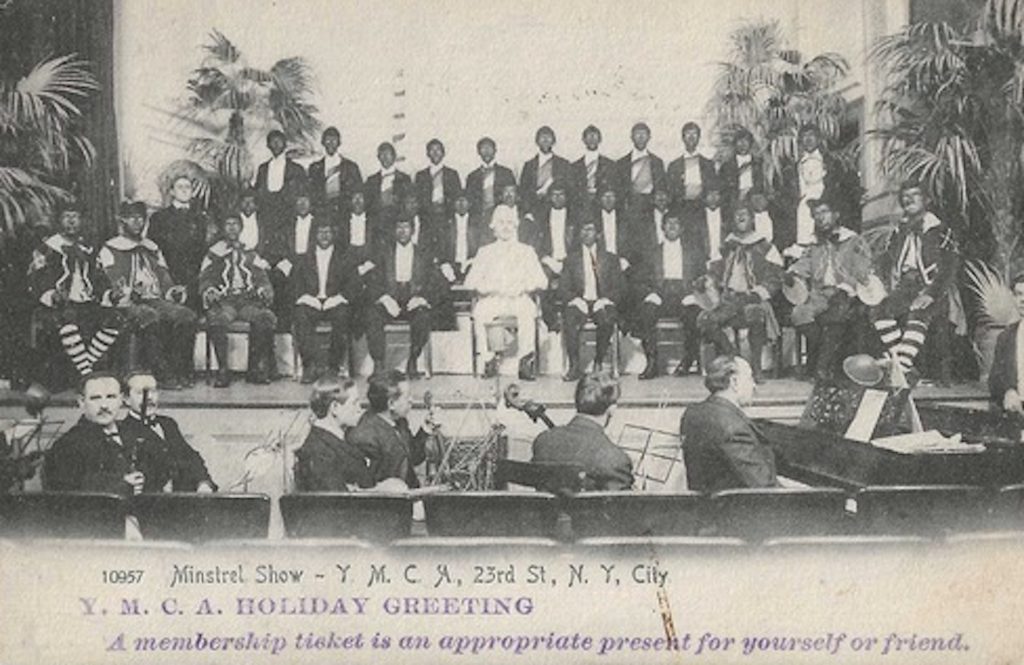

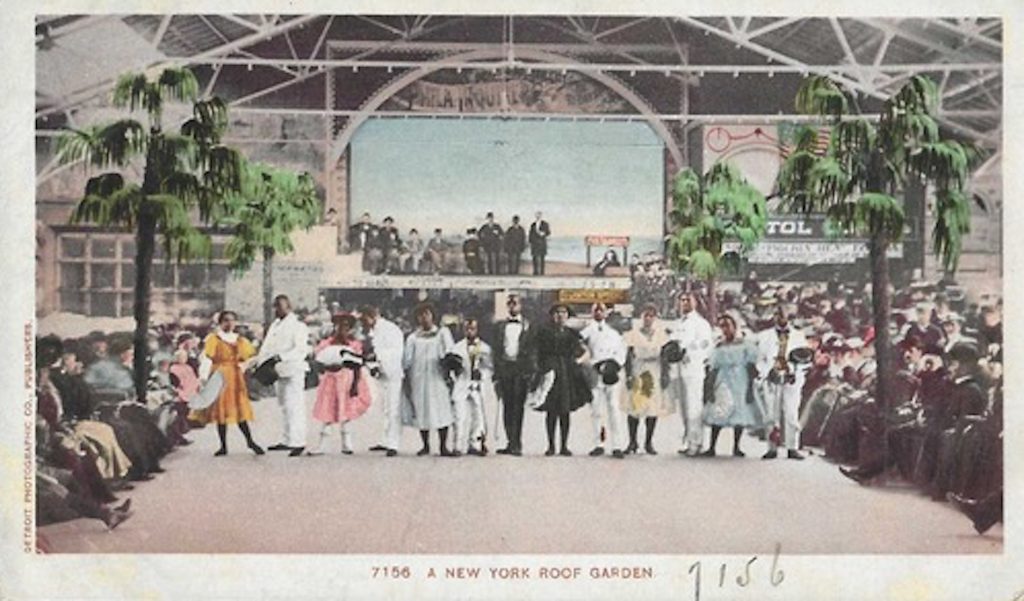

Prior to the 1920s, much popular African American music and dance had been rooted in the “blackface” and minstrel traditions and stereotypes of Southern plantation life during and after slavery days. The cards shown below by Rotograph and Detroit Photographic from about 1905 illustrate one of the most shameful aspects of minstrelsy – that it often involved whites performing as blacks in demeaning and offensive roles.

The “Cake Walk” another dance and performance style drawn from Southern Plantation days was a popular representation of African American arts at the dawn of the postcard craze.

The Harlem neighborhood had good housing stock and infrastructure such as public transportation, theatres and retail establishments developed in the 19th century. Aspiring upper middle-class Jews and Italians seeking a move up from the tenement neighborhoods into which their newly immigrating co-religionists and ethnic peers were crowding created an amenity-rich Harlem. Uptown was even starting to develop a night life in places like the Harlem Casino and the Ritz.

Harlem Nights in the 1920s became a laboratory for the development of black music – mostly what came to be known as Swing and Blues, musical forms related to Jazz. One hundred and twenty-five entertainment venues were in operation, including speakeasies, cellars, lounges, cafes, taverns, supper clubs, rib joints, theaters, dance halls, and bars and grills. Some of the best of these issued postcards that have become important American historical documents.

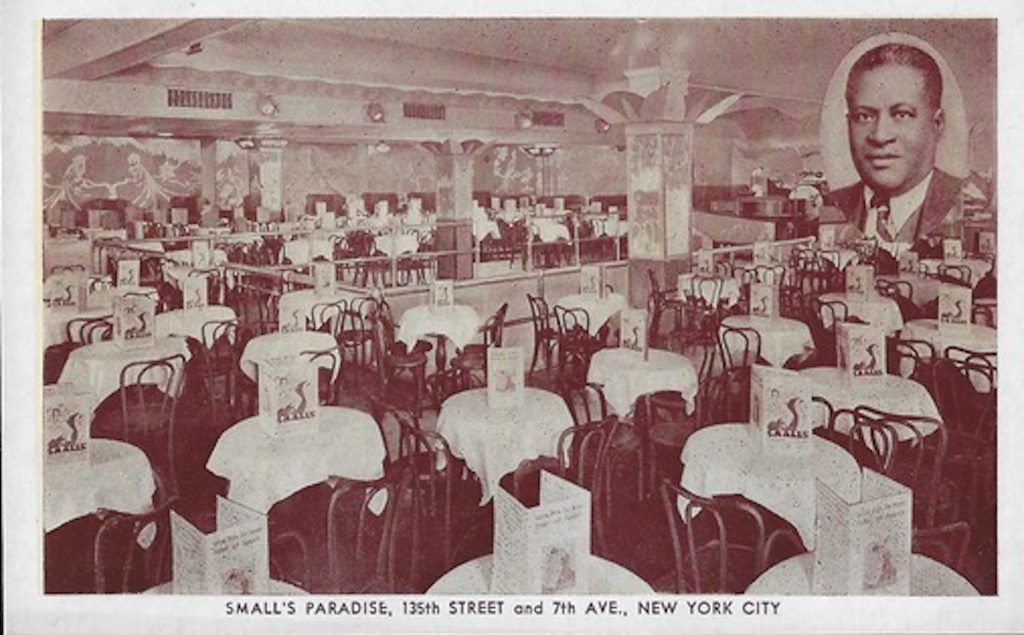

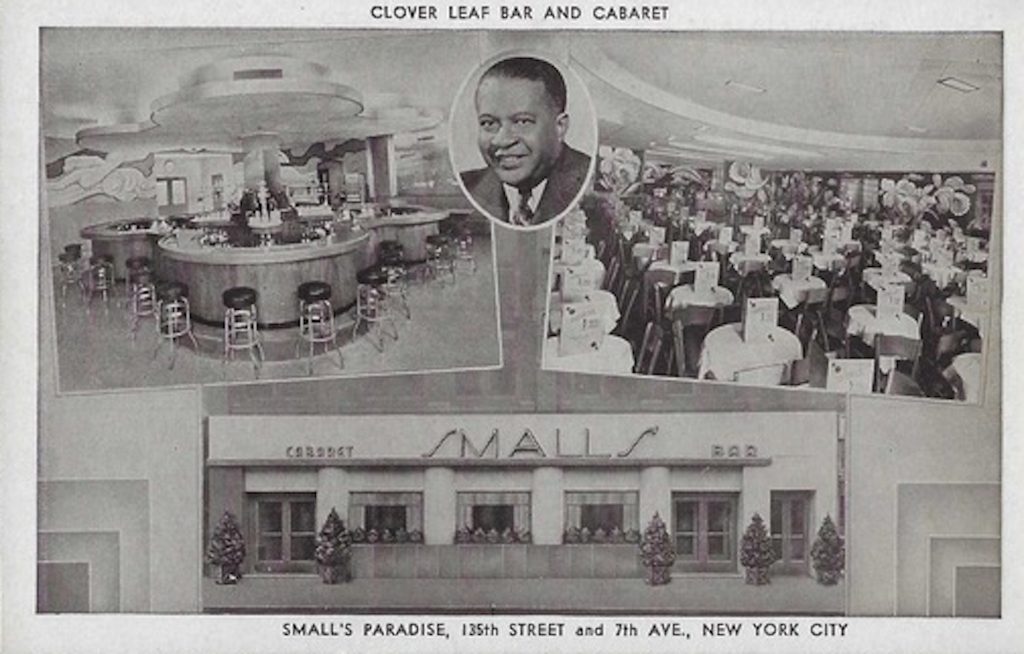

The most enduring of Harlem nightclubs was Small’s Paradise which opened in 1925 and remained vital until 1986. Unlike its main competitors during the early years, the Cotton Club and Connie’s Inn, Ed Small’s place was owned by an African American and had an integrationist policy. The injustices of racism were not absent in some venues like the Cotton Club that discouraged blacks from mingling with white customers, unless they were celebrities.

Small’s was unique in other ways. Its waiters would often appear in roller skates and join in on the music or dance action. The place ran through the night and began a breakfast dance at 6 a.m. The “house band” at Small’s included Charlie Johnson, Benny Carter and Sidney Bechet. Top-shelf white performers like Tommy Dorsey, Glenn Miller and Buddy Rich would often come by to jam with the house band.

In the early 60s, basketball legend Wilt Chamberlain bought a controlling interest in the club and renamed it Big Wilt’s Small’s Paradise. His management team modified the format a bit, inviting Blues artists like Ray Charles and comedians like the raunchy Redd Foxx, who toned down his act when he became a major TV performer in Sanford and Son. During the Twist craze, Big Wilt’s became a showcase for swiveling sacroiliacs.

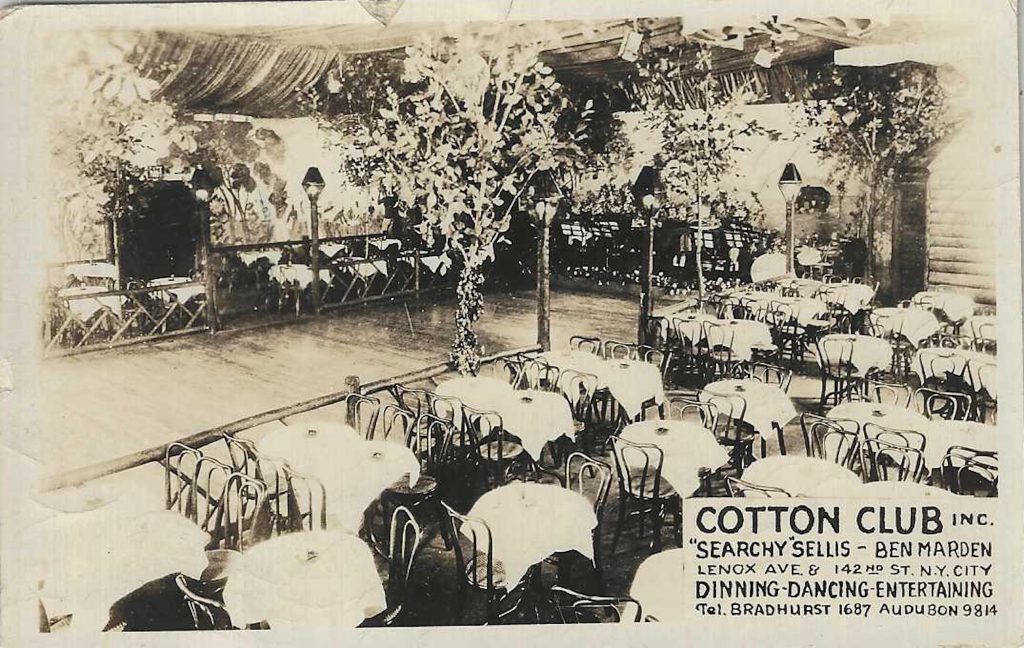

Even though it was subjected to demeaning segregationist rules, The Cotton Club featured numerous A-list performers, notably Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway and Jimmie Lunceford accompanied by Ethel Waters, Lena Horne, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and many others. During Prohibition years in the 1920s, the club’s major investors were underworld figures using the venue as an outlet for illegal beer sales. As Prohibition waned, the Cotton Club began to relax its segregationist policies. Eventually, the night club could not resist a move out of Harlem and settled in at the crossroads of 7th Avenue and Broadway at the heart of Times Square.

Courtesy of the Bob Stonehill Collection

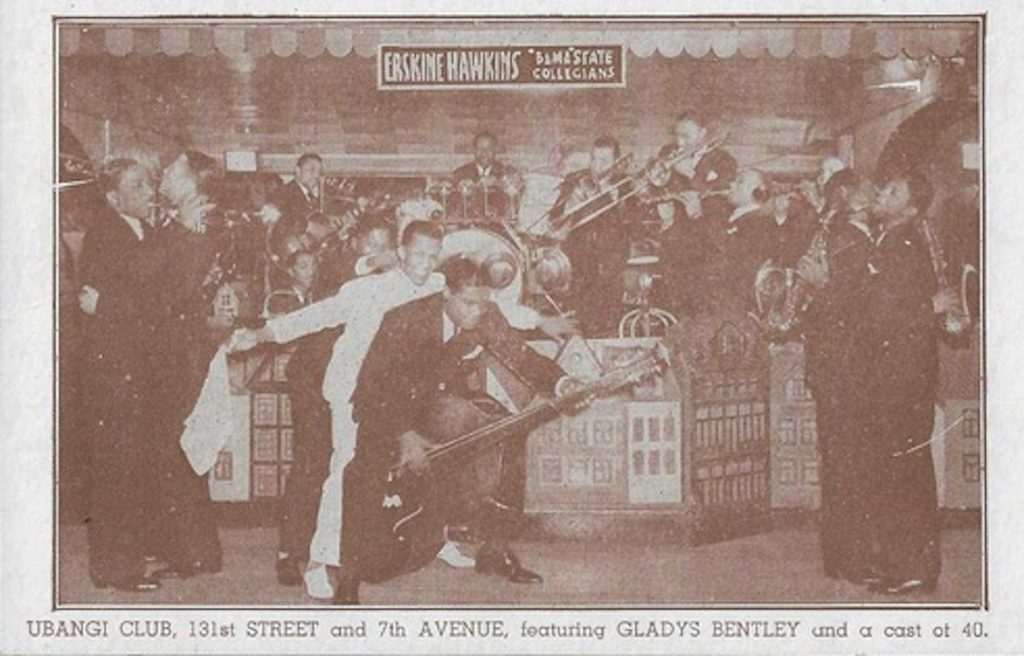

Connie’s Inn took a similar path as the Cotton Club, running a bootlegger’s gin mill in Harlem that showcased African American performers, like Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller and Fletcher Henderson, while restricting their audiences to whites. They also took off downtown eventually, leaving their venue at Seventh Avenue and 131st Street to be taken over by one of Harlem’s most unique night clubs, The Ubangi Club.

As far as we can tell, the Ubangi was an openly gay club that nobody had trouble with as long as it was up in Harlem. It’s the earliest card I know (from NYC) that featured gay couples dancing. It doesn’t show Gladys Bentley but she was an out lesbian performer who dressed in a gold lame tuxedo and top hat and said dirty things to the girls. The unique arrangement of the musicians on this card could also be described as “provocative.”

Harlem’s unique dance clubs also played an important role in showcasing emerging African American arts. Chief among these was the pink-painted Savoy Ballroom on Lenox Avenue where the “Lindy Hop,” also known as the “Jitterbug” reigned supreme and devotees could spend most of the night negotiating its flying jumpy moves. During the 1930s, the Savoy’s most popular band leader was Chick Webb, whose reputation only grew after 1934 when he hired on the winner of a singing contest at the famous Apollo Theater, a teenager named Ella Fitzgerald.

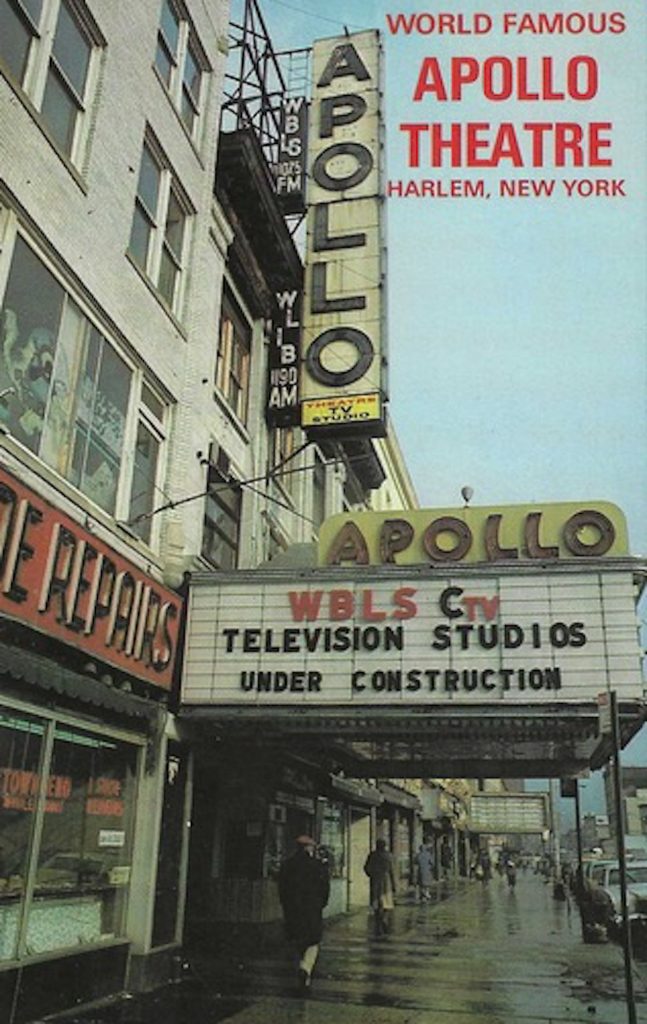

Two cards below illustrate the Apollo’s location and evolution: First a linen-era street scene of 125th, showing the Apollo and other theaters that shared the block. The next card shows the venerable old theater several decades after its heyday when it had become a studio and headquarters for several other black-oriented media properties.

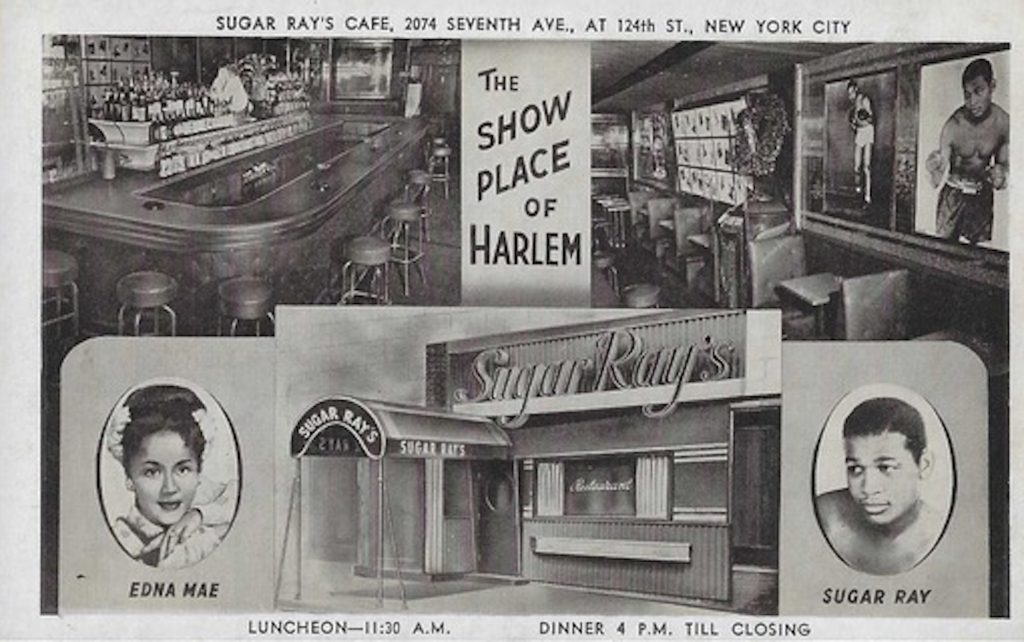

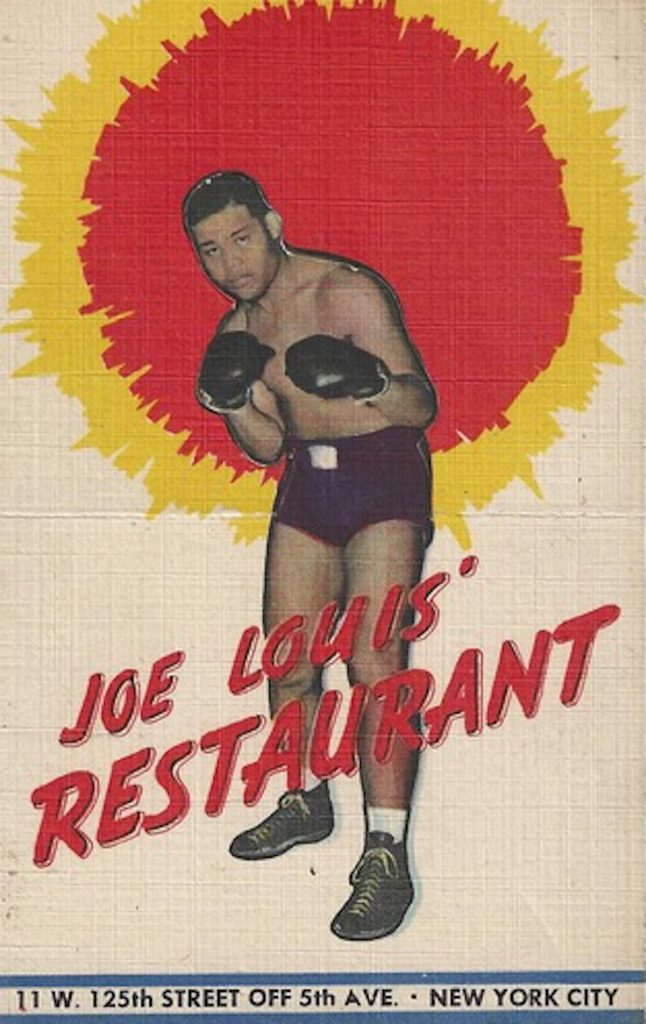

Harlem has always been proud and indulgent toward its sports heroes who took their winnings and invested in community night spots. None were as venerated in their day as World Heavyweight Champ Joe Louis and Welterweight Champ Sugar Ray Robinson.

In the June 22, 1938 rematch between Germany’s Max Schmeling and Joe Louis, the sharecropper’s son and grandson of freed American slaves, the “Brown Bomber” personified the aspirations of not just Harlem and African Americans but of every freedom-loving person in America and the world beyond. Schmeling was knocked out in a fight lasting two minutes and four seconds.

Ambitious and inspiring as a prize fighter, Sugar Ray Robinson was an eager teacher and mentor at his church and community-based youth programs. He loved being the center of attention at his club where he could show off his pink Cadillac and numerous souvenirs of a successful career.

Harlem began losing its verve as the unique place for black music as the 30s and 40s swung into the 50s and 60s. This was due to a combination of factors: partly the effects of the Great Depression and race riots that occurred in 1935, 1943 and into the 1960s. The big clubs and the big band sound were able to move downtown – closer to where their white audiences wanted them. Even the notorious Ubangi Club moved down to the Times Square area by 1943.

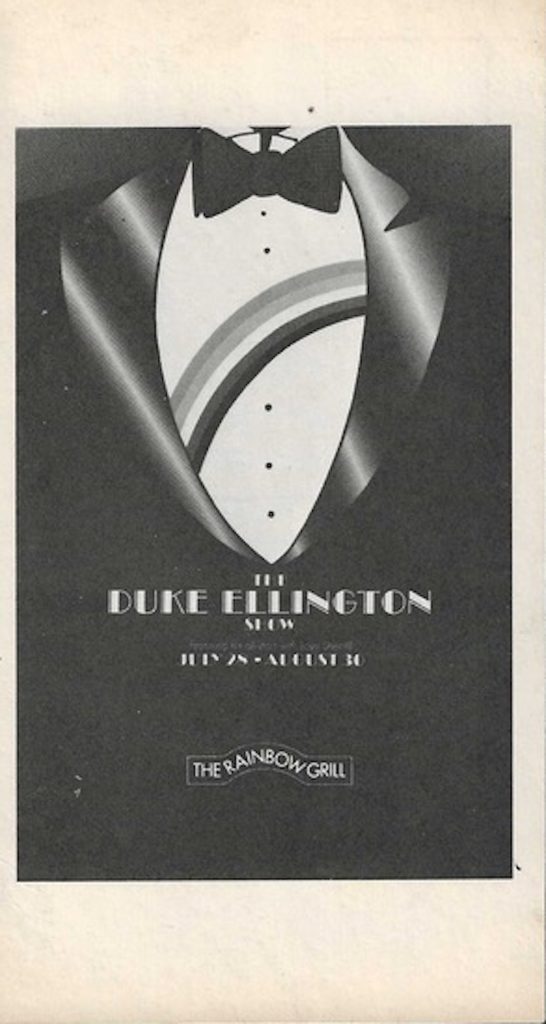

Harlem also became a victim of its own success, suddenly being mainstreamed into the era’s films, Broadway musicals and popular radio entertainment. Big name performers gained greater acceptance and started getting gigs at the City’s major venues. The cards below show an ad for an appearance by Duke Ellington at the Rainbow Grill, New York’s newest and poshest Art Deco inspired nightclub at the top of Rockefeller Center. The enormously talented pianist and singer Hazel Scott used a postcard to announce her appearance at Café Society, a nightclub explicitly devoted to racial healing that avoided any exclusionary or segregationist policies.

As Swing and African American musical styles were inching closer to the center of

American music, the great Benny Goodman’s January 16, 1938 Carnegie Hall Jazz Concert became a watershed moment for this art form – the first time a Swing program was being performed at New York’s premiere classical concert venue. Recordings of the concert – an ambitious effort to demonstrate the antecedents and varieties of Swing – were the first of the genre to sell a million copies. It would guarantee that Harlem Nights of the 1920s and 30s would join Vienna, Milan, and Paris as objects of study in the great musical conservatories.

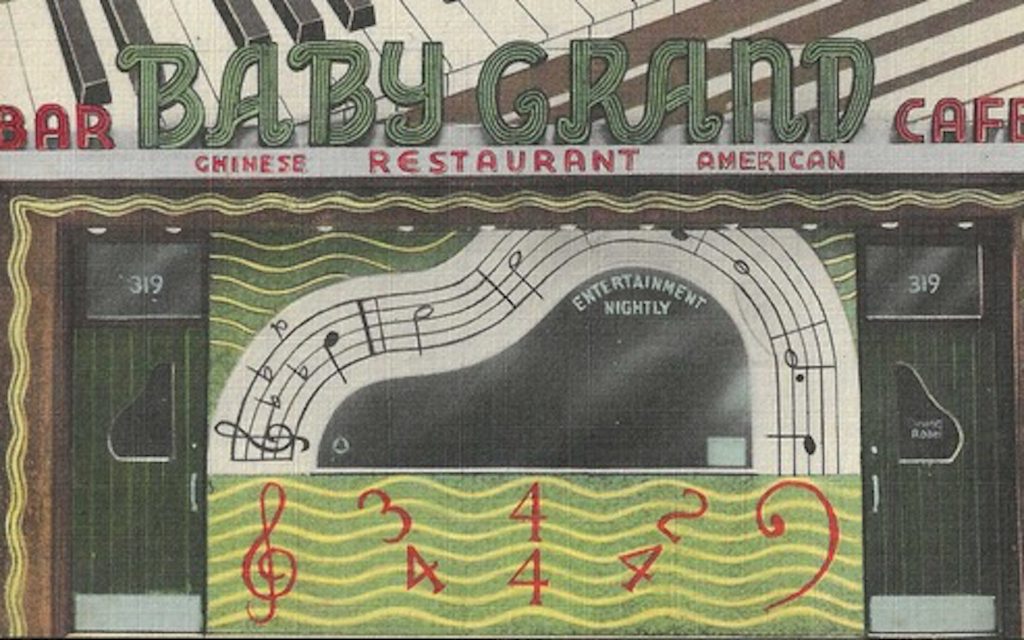

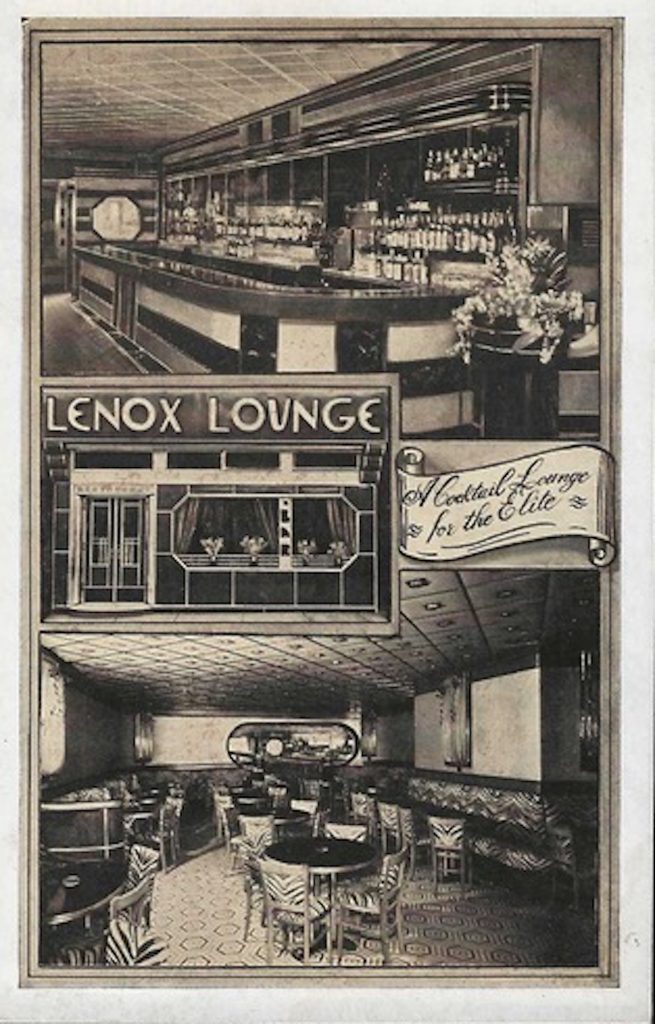

At the same time, new intimate styles and sounds and a new generation of performers began vying for an audience. Bebop and Latin Jazz delivered by Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie and many others started oozing out of clubs in Times Square, on 52nd Street and in Greenwich Village. Even in Harlem the action shifted to smaller joints like Count Basie’s, Minton’s, the Baby Grand and the Lenox Lounge.

As the 50s merged into the 60s and beyond, the Classic Jazz styles did not have an easy time. Family formation during the postwar “baby boom,” suburbanization and the newly invented mass medium of television conspired to keep people at home and out of nightclubs. Many Jazz performers were forced to seek audiences in Europe and Asia. Entertainers were able to reach out to new audiences – sometimes adjusting their styles – and find new enthusiasts through broadcast television but time was not on their side. Waiting in the wings were the youth subculture and the rise of rock’n’roll. However, that’s a whole other story.

Excellent history, with amazing illustrative period postcards!

Excellent article. Beautifully written. Loved the cards 😊

We just read and marveled over the historic and musical stories of this part of your postcard collection, Hy. We’d both read about the Great Migration but I, at least, never associated it with the rise of Harlem restaurants, nightclubs and jazz. Seeing the black-face entertainment made us cringe with shame. In my 20s I went to a lot of jazz clubs with my first husband and grew to love the music. As always, your writing and insights are perfection. I’m so sorry I never thought to have you Zoom for our Lifelong Learners. We’re all booked through fall, winter,… Read more »

Another super NYC postcard story! Thanks Hy!!

I do miss seeing the later view of the venerable Apollo, and am curious about the owners/management of the clubs that thrived and moved downtown. What was their racial make-up?

Also… the Ubangi card is the first vintage glimpse of Black gays I’ve seen out of the many lighter skinned images that turn up.

Kudos to Hy and postcardhistory.net.

Well, now the missing Apollo has appeared. Thank you gods of my iphone.

Thanks for another colorful piece of history via postcards! I learned several details, such as how Ella Fitzgerald got her big break.

Also, I noticed that on one card the sender still had to write his message over the picture! I’d be curious to see the back side of another to see if it was split with room for both the note and the address!

Many thanks, Hy, and enjoy your Summer travels. We’ve had a lot of company here.

Great Article Hy. Easy to read and chuck full of information, some of it new to me. Wonderful rare postcards not often seen or found in the postcard market. Thanks for continuing to enlighten us via postcards.

Outstanding article… Once again Hy opens a window into one of our dynamic New York City neighborhoods with his masterful story telling and then invites us to peer in further through his fabulous postcard images.

Great article with wonderful Art Deco postcards

Interesting that the Baby Grand featured Chinese food, as opposed to the ribs or steaks more typically associated with places where black entertainers performed.

Through zoom I have learned to recognize both the voice and the face of this author, Hy Mariampolski. How LUCKY we all are to have this nice man share some of the great postcards from his collection and to tell about them. I have never seen the majority of the postcards here or in any of the presentations that he gives at the “Wish You Were Here” lecture series. Postcards teach us so much and this article about Harlem is outstanding, and worthy of several re-readings. It is just so marvelous that such quality postcards exist and fortunate for us… Read more »

A very interesting article. When I was a member of the Old Dominion Postcard Club in Richmond, Virginia in the early 1980’s, we had an African-American member who indicated it was very difficult to find postcards related to African-Americans. In my collections of a over two hundred Virginia postcards, I only have three postcards related to the African-American community. Two are of African-American colleges and and the other of a high school. Dr. Mariampolski has done an excellent job of showcasing the African-American experience in NYC. No doubt other ethnic groups were ignored by local postcard publishers.

Another excellent NYC history lesson and outstanding postcards. Thanks, Hy.

Great article and really exceptional cards that make Harlem really come alive.

Interesting article with great postcards, I also collect old old postcards of New York including nightclubs and restaurants but unfortunately don¬t have any of these.

Learned a great deal from the article. Awed by the outstanding postcards. Many thanks to the author for sharing his talents and collection.

What a wonderful article, Hy!!!!!!