There was a time in New York City that you could arrive at a fabulous hostelry by Checker taxi with enough room for some extra luggage or companions. Then, following shopping, work or entertainment during the days, spend your nights in the same hotel diverted by the best singers, orchestral acts, and dancers in show business. If the shows got a bit tedious, you could run over to nearby competing hotels and nightclubs in Times Square, near Penn Station or on the East Side for late shows into the morning hours. New York was the place to be in the Pre-War, Wartime and Postwar years for patrons and performers alike. Neither the economic dislocations of the Great Depression nor storm clouds of war could repress the investment and The Astor, The Waldorf-Astoria, The Pennsylvania, The Martinique, The New Yorker and others became legendary over-the-top hotels. Today, even the iconic Hotel Pennsylvania, which once had a song named for its phone number, is being replaced by a 68-story office tower. Little remains to memorialize the good times of yore besides the images and messages of the period’s picture postcards.

The Astor was a marvel of French Beaux Arts design that presided over Times Square since its inception as heart of the theater district in 1904. The latest technology – electric illumination turning nighttime into day was a marvel. The space alongside the front of the hotel called itself “The Gay White Way,” and was singularly an object of wonderment and artistic inspiration as in this 1924 Poster View of New York by A. Broun. Along with the Hotels Knickerbocker and Waldorf-Astoria, the Astor was built and expanded by its namesake family, which had accumulated astonishing wealth through real estate ownership and development in a vastly growing New York City. The hotel’s opulent character led to the emergence of Times Square as an entertainment center. Along with its Roof Garden, which set the pace for similar amenities all over New York, the Astor boasted L’Orangerie as a spectacular space for Edwardian night owls. The Tommy Dorsey Orchestra held forth on the roof as regulars during the Swing Era and it was there in 1940 that they introduced a young New Jersey crooner named Frank Sinatra.

In its mature years, the Astor became known as a pickup bar for both straight and gay folks. Its reputation was popularized in the suggestive song “She Had to Go and Lose It at the Astor” sung by Pearl Bailey, among others. These traditions were ended when the hotel was torn down in 1967 and replaced by One Astor Plaza, another 60-story office building. Built practically around the corner from the Astor in 1927, the Hotel Paramount was the only hotel designed by theatrical architect Thomas W. Lamb. Brought back from oblivion in the late 1980s by master lodging and entertainment entrepreneurs Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell, the hotel’s interior has featured a stunning redesign of its French Renaissance spaces by Philippe Starck, the French master designer. In its heyday, the hotel was appreciated for its flamboyant Art Deco Paramount Grill, occasionally presided over by Charlie Barnett, jazz saxophonist known for his hard driving style and commitment to racial healing. This 1932 miniature postcard announces the appearance by band leader Ozzie Nelson, known a generation later as the sympathetic paterfamilias of the television Nelsons, in which he appeared with his wife and former singing star Harriet Hilliard, along with their sons David and Ricky.

The basement of the Hotel Paramount was also the location of the Billy Rose Diamond Horseshoe nightclub, known for its bevvies of beauties competing against similarly gowned women across the street at the Latin Quarter. Billy Rose’s renown as a pundit of pulchritude was established during the 1939 New York World’s Fair when he dazzled the crowds with his “Aquacade,” a synchronized swimming spectacle.

Known as the Hotel Dixie when it first opened in 1930 with 1000 rooms near 8th Avenue between 42nd and 43rd, this property had a troubled history emblematic of the decline of Times Square, without experiencing the rebirth that renovated the strip and many of its attractions starting in the 1980s. Losing a chunk of its structure that eliminated access to 42nd Street, going through a series of unhelpful ownership changes and rebranding itself as the Hotel Carter, this place eventually became reputed as “the dirtiest hotel in New York.” The Carter also became known as the venue for a long series of suicides, murders and other crimes leading to its closing in 2017. Despite the hotel’s ultimate denouement, the happy zany times when Al Trace and his 10 Silly Symphonists presided over the Plantation Room of the Hotel Dixie are preserved in this 1930s Linen card published by Colourpicture.

The Hotel Capitol no longer exists although its space is today occupied by a very modern-looking modestly priced hostelry in the North Times Square area that offers many amenities to its business and tourist customers. In its day, however, this was the location of Nicky Blair’s Carnival, a madcap comedy club with vaudeville-like burlesque, featuring the best up and coming funny-makers just before they became fixtures on home television sets. Milton Berle, George Jessel and others were regulars, like the people advertised on the postcard below: “Olsen & Johnson, Beatrice Kay and America’s Loveliest Girls in a spectacular revue staged by John Murray Anderson.” Blair, born in Brooklyn as Nicholas Macario, besides being a noted bicoastal restaurateur featuring his Nonna’s dishes, was also a perennial bit-part performer in dozens of films, including Viva Las Vegas and Godfather III. Anderson was a preeminent Broadway teacher (Lucille Ball and Betty Davis,) producer (Greenwich Village Follies, Ziegfeld Follies,) and director working with the likes of Ira Gershwin, Yip Harburg and Billy Rose.

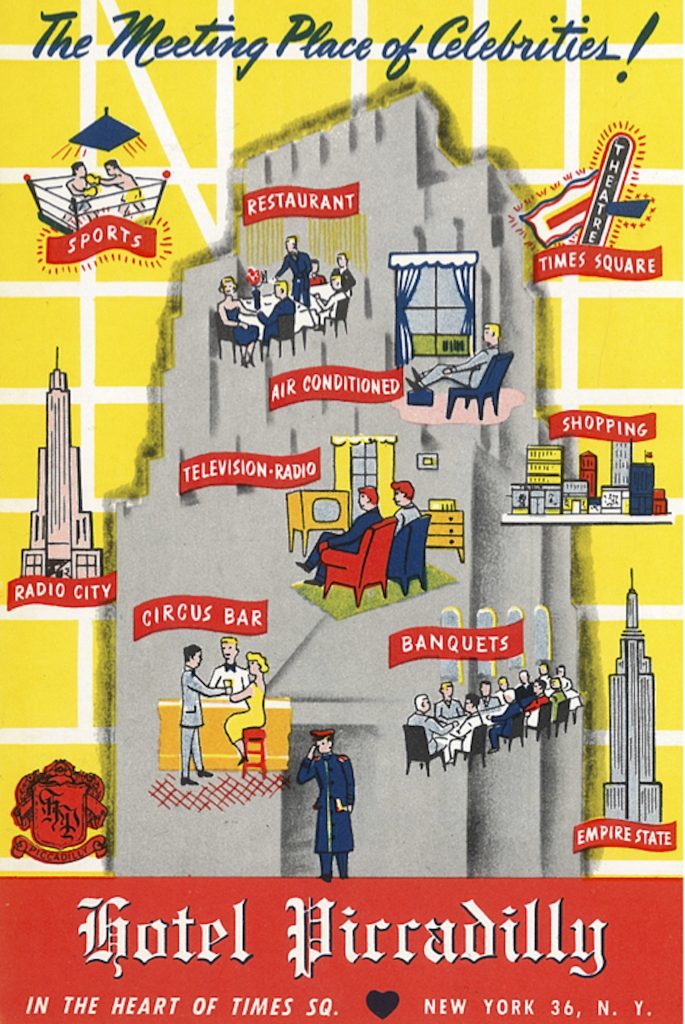

The Hotel Piccadilly reached for the stars when it was first constructed on 45th Street as a 600+ room Art Deco monument in 1928. It had a good life, as they say, but after falling out of fashion and going into physical decline as the Times Square area was crumbling in the 60s and 70s, the Piccadilly met the wrecking ball in 1982 and was replaced by the Marriott Marquis Hotel, which continues to occupy the site. Named for the popular West End London Street, also known as the heart of their theater district, the Piccadilly aspired to be center of action where the show people could mingle with the show goers. The destruction of the Piccadilly was quite controversial at that time, not just because of the hotel’s demise but also because three neighboring theaters, the Morosco, Bijou, and Helen Hayes were torn down along with the hotel. The central element of the Piccadilly’s outreach was its ever-popular Circus Lounge, which sometimes promoted its acts with attractive postcards.

Not yet exhausted after being on a roll of late-night partying? – Don’t worry. New York offered plenty more hotel ballrooms where you could indulge your last drop of energy before drifting off to sleep and getting ready for the next day’s immoderation. Next stop, walking just a mile South from Times Square – the Hotel New Yorker.

Of the “famed trio of Clayton, Jackson & Durante” advertised on the Paramount Grill postcard, Jimmy Durante is the only man whose name I recognize.

Lou Clayton and Eddie Jackson started out in a vaudeville act together with Jimmy Durante. Jimmy’s breakaway hit was “Inka Dinka Doo” in 1933 a song from the musical adaptation of the cartoon strip Joe Palooka. Afterwards, he was a solo act appearing frequently on early television. His signature farewell was “Goodnight Mrs. Calabash wherever you are…”

Great articles Hy. Beautiful cards. Fascinating History!

You are confusing two different Nicky Blairs. The NYC Saloon operator and the actor/Los Angeles restauranteur were different people.