There’s a word that we see on some postcards, perhaps a restaurant from New York or a resort in Miami. Maybe you noticed that word on a postcard from a small hotel in Monticello in upstate New York.

The word is “kosher” and it makes you laugh sometimes because you’ve heard it used in a punchline by a Jewish-American comedian when discussing something “accomplished” by a politician, as in, “Don’t worry about the Feds, it’s completely kosher.”

Restaurants that target Jewish customers or that offer foods that appeal to Jewish persons often identify themselves as Kosher. With 1.6 million Jews living in New York City (2022,) you figure lots of them are looking for a “nosh” (edible treat) fairly frequently. However, as we will see, this “kosher” designation as a way of identifying Jewish dishes is problematic.

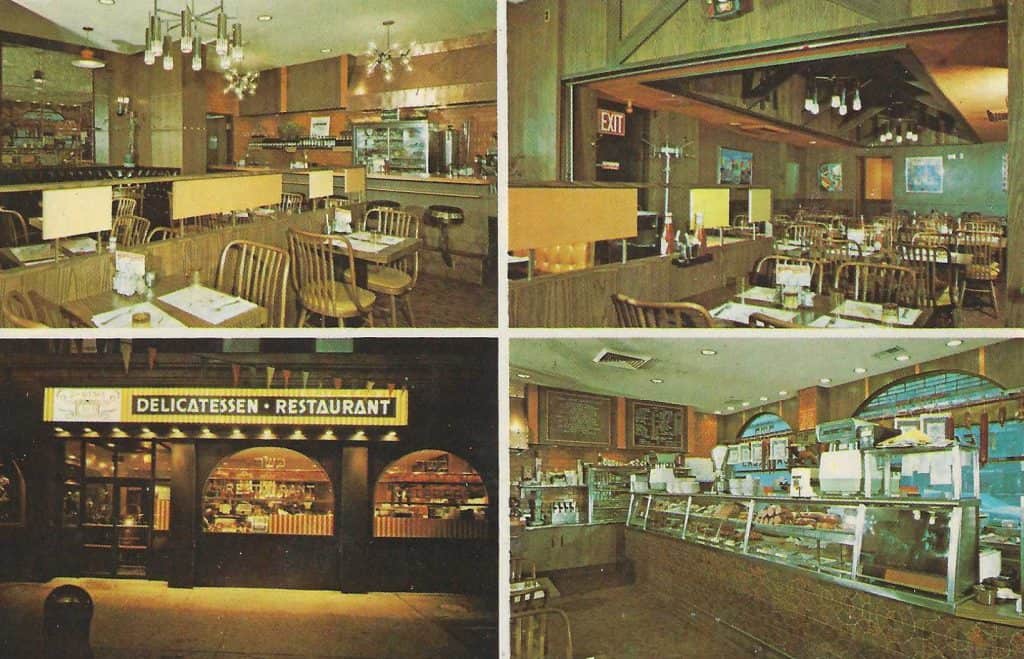

You see the term “kosher” on some of our oldest Jewish restaurant cards as well as some of our newest. Poliacoff’s on West 45th Street in the Theater District claimed to be a “strictly kosher restaurant.” The 2nd Avenue Delicatessen Restaurant at 10th Street on the Lower East Side describes itself as “A Gourmet’s Rendezvous for the Finest Kosher Cuisine in New York.”

Kosher (alternatively, Kashrut in Modern Hebrew) is a religious concept and like other ideas associated with religious faith, beliefs that appear obvious and clear to those who have grown up within a tradition, seem obtuse and impenetrable to those coming from outside that body of religious orthodoxy. So, we are challenged here when discussing Kashrut to be simple and avoid unnecessary complexity.

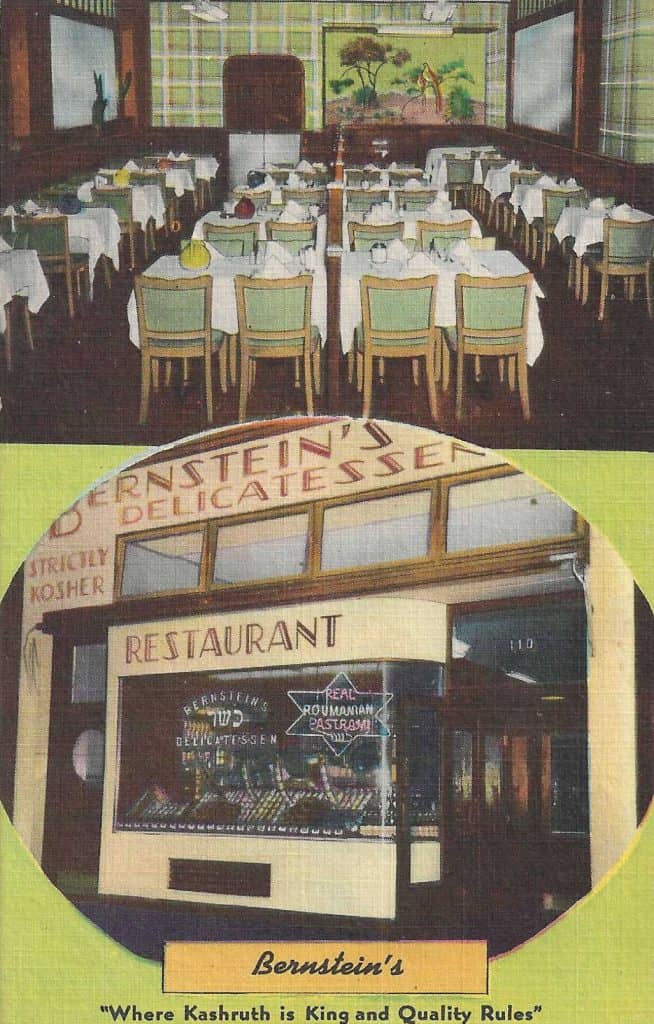

At its core, Kosher signifies a food that has been demonstrated to be suitable for consumption by religiously observant Jewish people. It starts with adherence to a body of rules that distinguish Kosher from non-Kosher foods. It’s a religious status that does not circumscribe a particular cuisine or type of food. The same is true of ethnically “Jewish” foods, like deli meats. They are not automatically kosher and must qualify based on their content, preparation, and ingredients. Not even chicken soup or knishes are automatically kosher without qualifying on specific criteria. At the same time, kitchens that serve non-Jewish cuisines can make them in a kosher way, like traditional restaurant Bernstein’s on Essex which offered Chinese dishes while reassuring those that adhered to Kosher laws that they could relax and enjoy their ethnically Chinese meal.

The rules make Kosher foods easily discernable, so they are recognized as legally enforceable. In most municipalities, you may not call something Kosher if it’s not because that violates laws associated with fraud. Rabbinical authorities try to make it all simple through a system of certifications and endorsements. The most common seal of approval is issued by the Orthodox Union, a “U” surrounded by an “O” on product labels. Other symbols representing other certifying bodies often compete against the Orthodox Union; the word “kosher” spelled with Hebrew characters is often used to gain credibility but is not a service mark.

Sometimes, establishments have tried to simplify this issue for their customers by referring to “dietary laws” being followed and avoiding the K-word. Many Jewish restaurants and delis avoid the issue and don’t mention Kashrut at all. That reveals a truth that’s confusing to some: Many if not most Jewish restaurants are not and have never been certifiably Kosher.

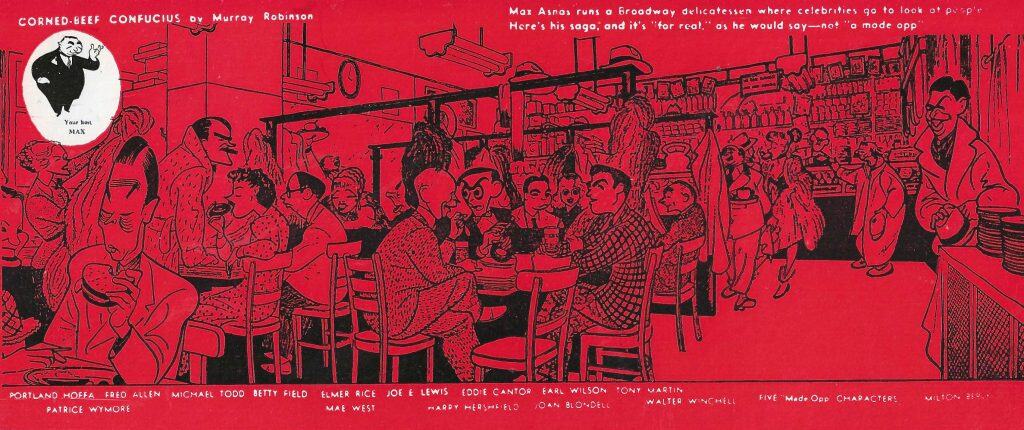

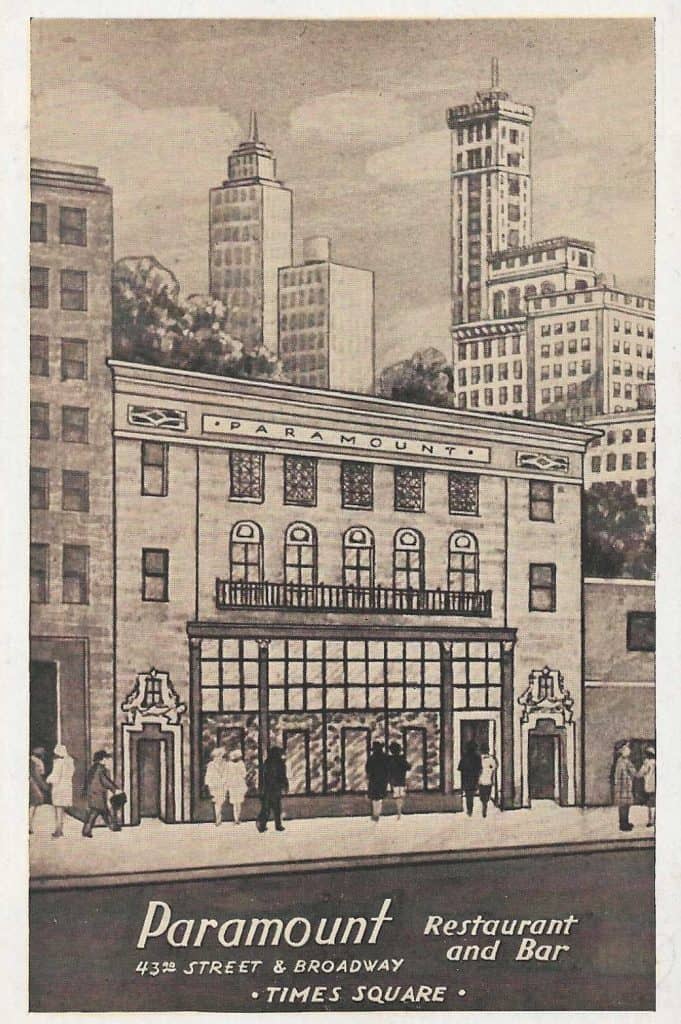

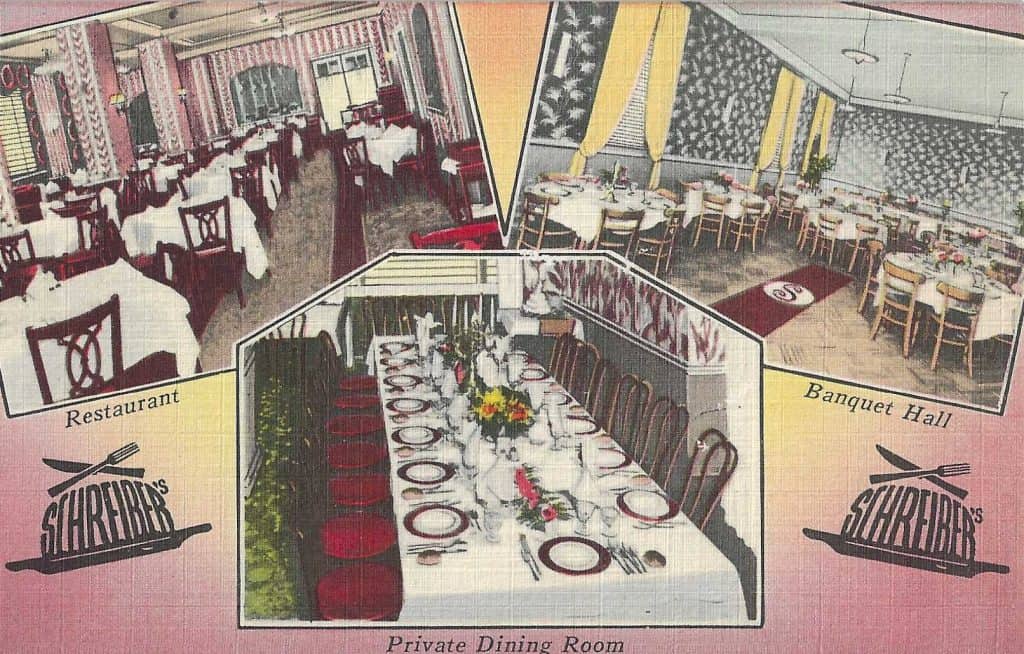

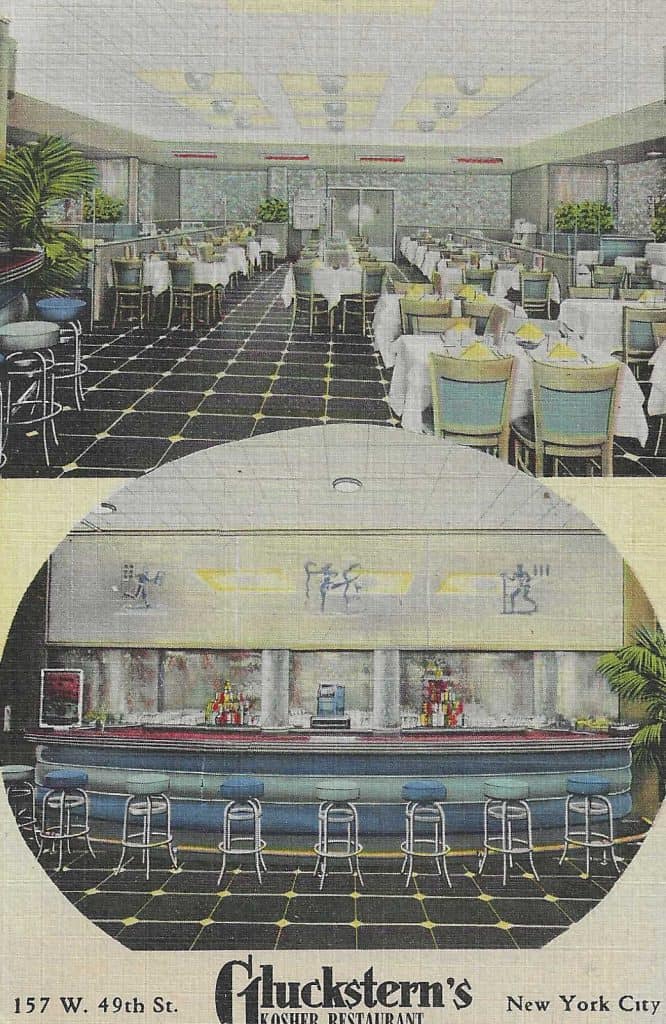

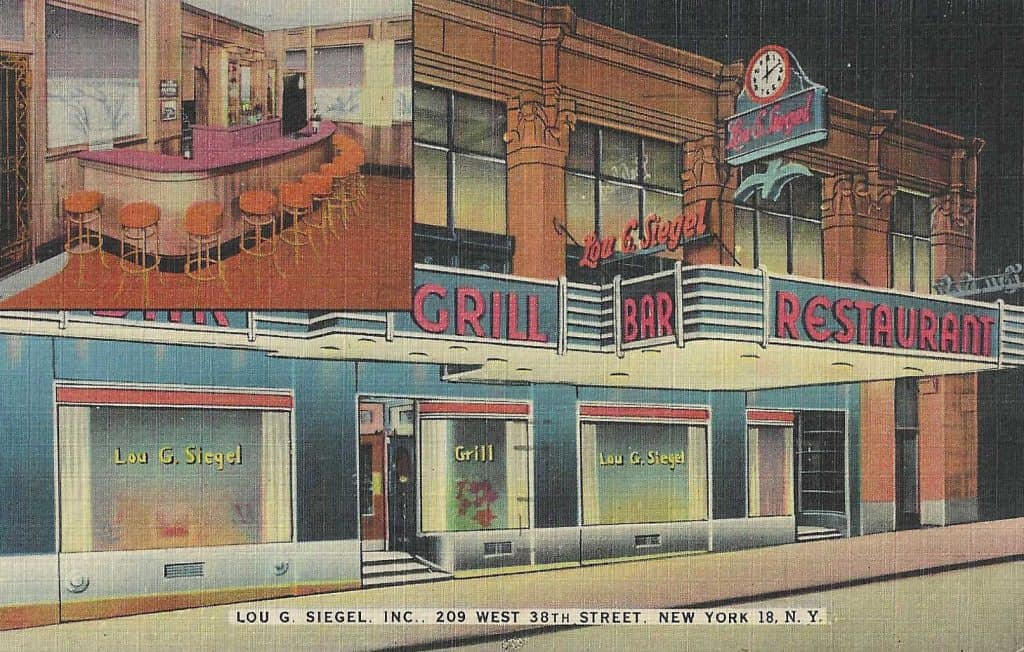

It was different in the early days. If we examine a collection of postcards in this category, the oldest ones do make claims about being Kosher: The Paramount Restaurant at 138 West 43rd Street in Times Square asserts it is “Where Kosher Food is served at its Best.” Nearby, Gluckstern’s is just a “Kosher Restaurant” at 157 West 49th Street. On the West Side, Schreiber’s Restaurant and Caterers describes itself as “Strictly Kosher.” Lou G. Siegel, who commissioned this magnificent linen ad from Boston’s Colourpicture goes full steam and stakes its claim as “America’s Foremost Kosher Restaurant.”

Many otherwise kosher restaurants have made themselves un-kosher at the dessert course by offering Jewish or Jewish-style pastries that contain dairy products, like cheesecake and Napoleons.

That gets us to the actual rules that distinguish kosher from non-kosher foods:

First, Kosher foods and ingredients need to come from a kosher animal – Cows, lambs, chickens, and salmon are kosher. Pigs, shrimp, snakes, and owls are never kosher. Rabbinical rules describe why any particular animal is considered kosher or not, for example, only fish and seafood with scales can be considered kosher. (NOTE: Describing all the rules is beyond the scope of this article. Please seek competent religious advice if you need answers to specific questions.)

Non-kosher ingredients are contaminating. A slice of bacon on a bagel with cream cheese makes the whole sandwich not kosher. Un-kosher foods are never “cleansed” by eating kosher foods alongside them.

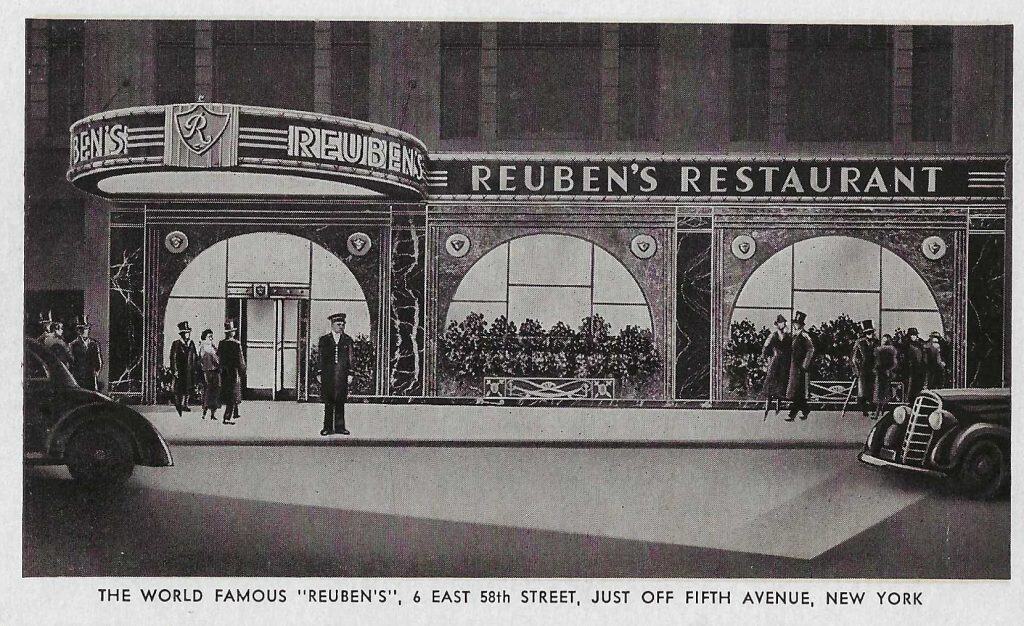

Next, kosher foods need to be prepared in certain ways, slaughtered properly, and by cutting away parts of even kosher animals. Food combinations must be considered when determining whether or not a dish or a meal is kosher. Specifically, meats may not be eaten together with dairy foods. For example, New York’s famous “Reuben Sandwich” coming from the eponymous restaurant is considered by many to be a Jewish treat. It’s a pretty tasty combination of corned beef, sauerkraut, Russian dressing, and Swiss cheese but it’s not Kosher, because it combines meat and dairy foods. Kosher delis for the same reason will not serve their hamburgers with a slice of blue or any other cheese. It’s a combination not allowed by the rules. NOTE: Reuben’s Restaurant was known as a Jewish food place and served many conventional Jewish foods like chopped liver sandwiches, “Gefuelte Fish,” etc. but never claimed to be Kosher.

Then, there is the distinction between just Kosher and “Strictly” or “Glatt” Kosher. This distinction is particularly important in neighborhoods with substantial “haredi” or “Hassidic” (strict practice) populations. It calls attention to the distinctly non-dietary qualification of Sabbath observance, that is, to qualify as strictly kosher, the food may not be prepared or sold on the Sabbath. Admittedly, this is a high reach but must be understood in the context of uncompromising adherence to the Kosher laws.

Much to everyone’s relief, fruits and vegetables have a relatively easy time under the rules.

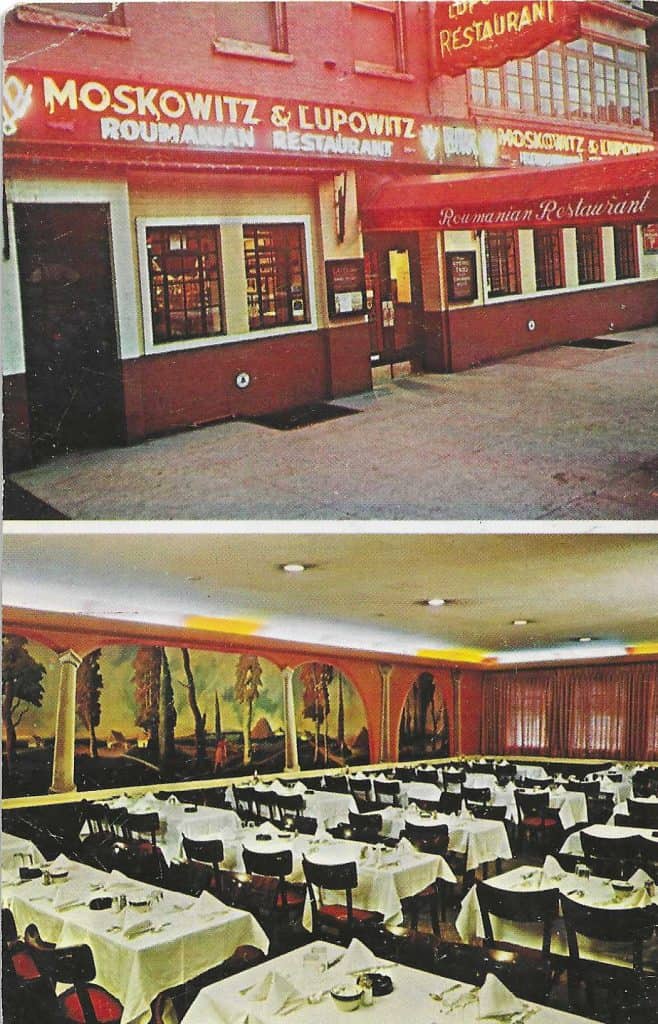

Jewish neighborhoods traditionally have three different types of restaurants and kosher laws are relevant in distinct ways for each. There are, first, full-service restaurants that serve complete meals. Nowadays, because of recent immigration patterns, some of these may be identified as Russian, Persian (Iranian), or Bokhari (Uzbek) due to their unique ethnic slant. In the last century, they might have been designated as Hungarian or Romanian, but these have receded as their underlying ethnic communities have assimilated. Until it vanished when New York’s Yiddish theater district lost steam in the 1970s, Moskowitz & Lupowitz at Second Avenue and Second Street in Manhattan was considered to be the pinnacle of Jewish restaurants with its extensive menu, jars of schmaltz (rendered chicken fat) and sour pickles at each table, and strolling gypsy violinists belting out anything from Russian Folk Tune, “Oczy Czarny” (Dark Eyes,) Sophie Tucker hit, “Mein Yiddishe Mamme” (My Jewish Mother,) to standards like “Summertime” by George Gershwin who grew up practically outside the restaurant’s doors.

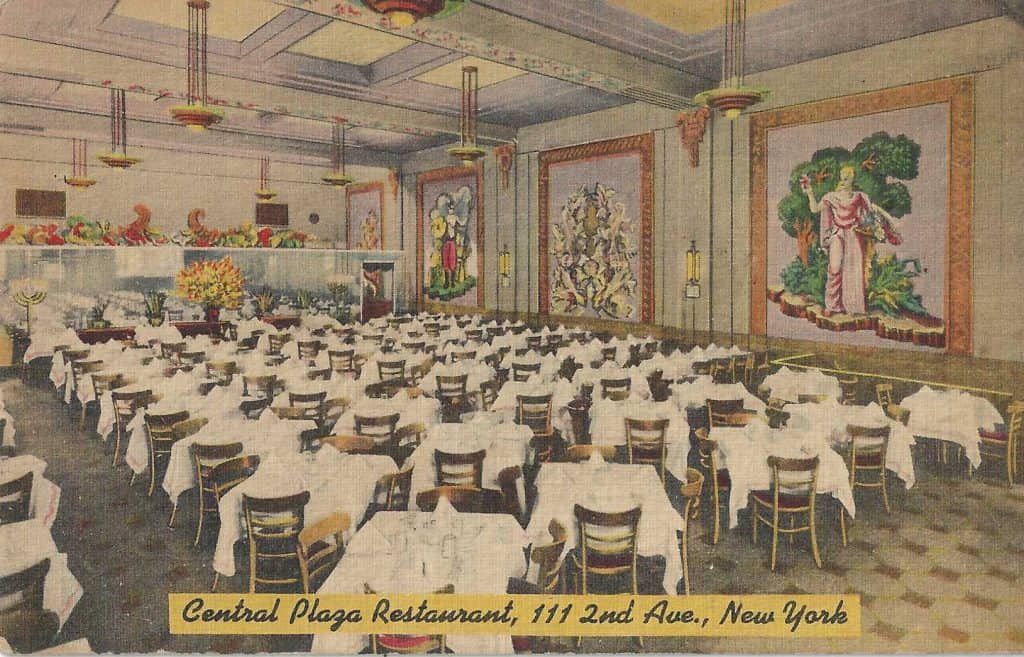

An old-time contender in the Lower East Side’s Yiddish Rialto was the Central Plaza Restaurant, at 111 2nd Avenue. The size and scale of many of these restaurants attest to their importance as celebratory venues for weddings, bar mitzvahs and circumcisions. Many of these restaurants would close for an event or maintain separate party spaces.

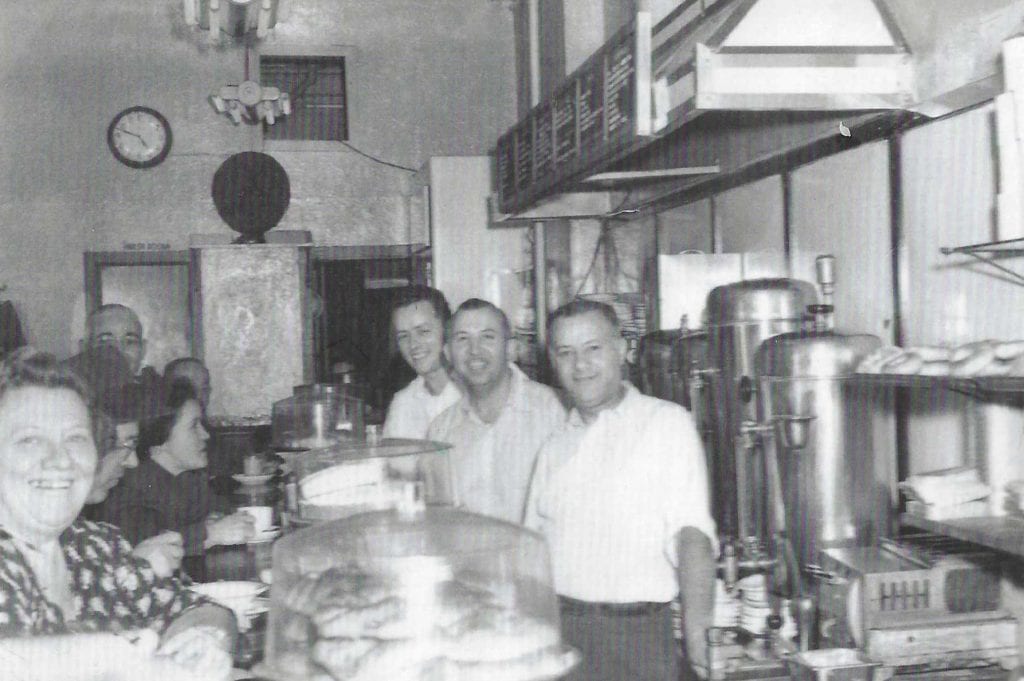

Another neighborhood classic is a narrow New York-style diner at the opposite end of the size and space dimension. B & H Dairy Kosher Vegetarian Restaurant goes back to 1938 and is still a great place to get a bowl of borscht (beet soup) or another one of their daily soup specials accompanied by a thick slice of rich challah (double-kneaded egg bread). What better way to let you know that this modest eatery has big yikhus (pedigree) than a giveaway postcard showing the restaurant’s founders during the 1940s.

daughter of B&H founder Abie Bergson.

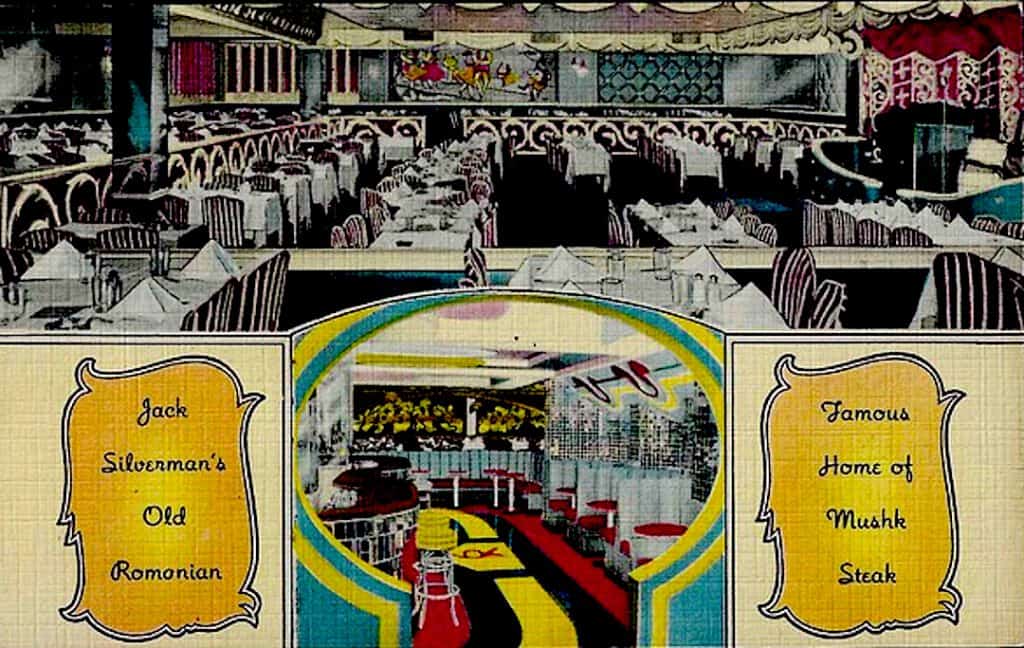

Nearby, Jack Silverman’s Old Romanian competed as a restaurant and night club. Mushk Steak, everyone will be relieved to know, is not meat taken from a small furry critter, but a concoction made from steak and kasha (buckwheat groats). Jack eventually moved his formula and contacts with top Jewish-oriented performers, like Myron Cohen and the Barry Sisters, uptown to Times Square where he opened his International Night Club.

The next variety of Jewish eatery, the Dairy Restaurant, is an adaptation to kosher laws since in its classic format it does not serve meat dishes at all. This type of restaurant also takes advantage of a quirk (or a feature) in the kosher laws that does not consider fish to be meat. So, the showcased dishes at most dairy restaurants are made with salmon, tuna, and whitefish. Back in the Golden Age, Ratner’s on Delancey Street near Stanton and the Garden Cafeteria on East Broadway at Strauss Square were the best reputed representatives of this category, where an extraordinary plate of Gefilte Fish (stuffed fish) or Kasha Varnishkes (Buckwheat groats with Butterfly Pasta) could take you right back to Grandma’s kitchen. The Garden located in the shadow of the building housing New York’s Yiddish Daily, the Forward, was renowned as the hangout for Yiddish poets and playwrights.

Nowadays, the best of the pickled and smoked fish or “appetizing” places is Russ and Daughters down on the Lower East Side at Houston and Allen Streets. Long known for its many varieties of herring, lox, whitefish, sable and chubs, the family decided to expand into a café around the corner with sit-down meal service. A multigenerational favorite of the Mariampolski clan, the store’s next generation has continued the successes of the Federman family.

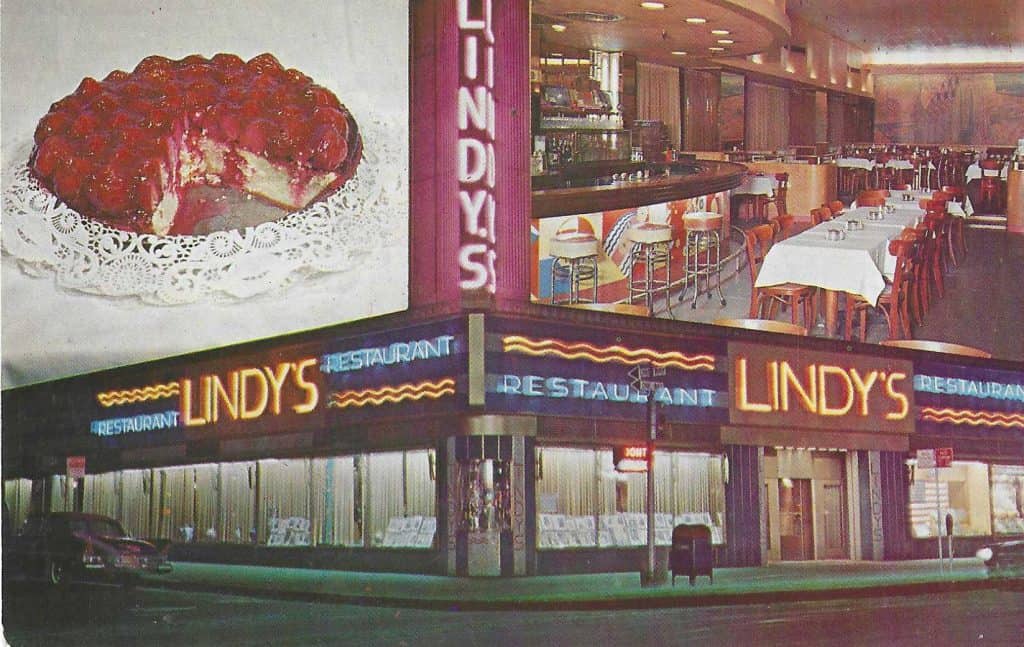

Regardless of what else is served there, some dairy restaurants are primarily places for dessert, usually Jewish-style moist and buttery cheesecake. A generation or two ago, the most popular of the dessert cafes was Lindy’s located at a variety of places around town but ending up at Broadway and 51st in the Theater District. Promoted by striking art-moderne postcards, today this brand has been replaced by Junior’s whose traditional deli and cheesecake HQ is on Flatbush Avenue in Downtown Brooklyn. In one of those acts of New York retail real estate poetry, Junior’s recently established its own Manhattan command center at the storefront formerly occupied by Lindy’s. Old time New Yorkers will remember that Lindy’s was the favorite hangout of Jewish Mafia Boss Arnold Rothstein who was last seen munching cheesecake there before being dispatched to “Olam Haba” (the world to come, i.e., heaven) in a gang rivalry.

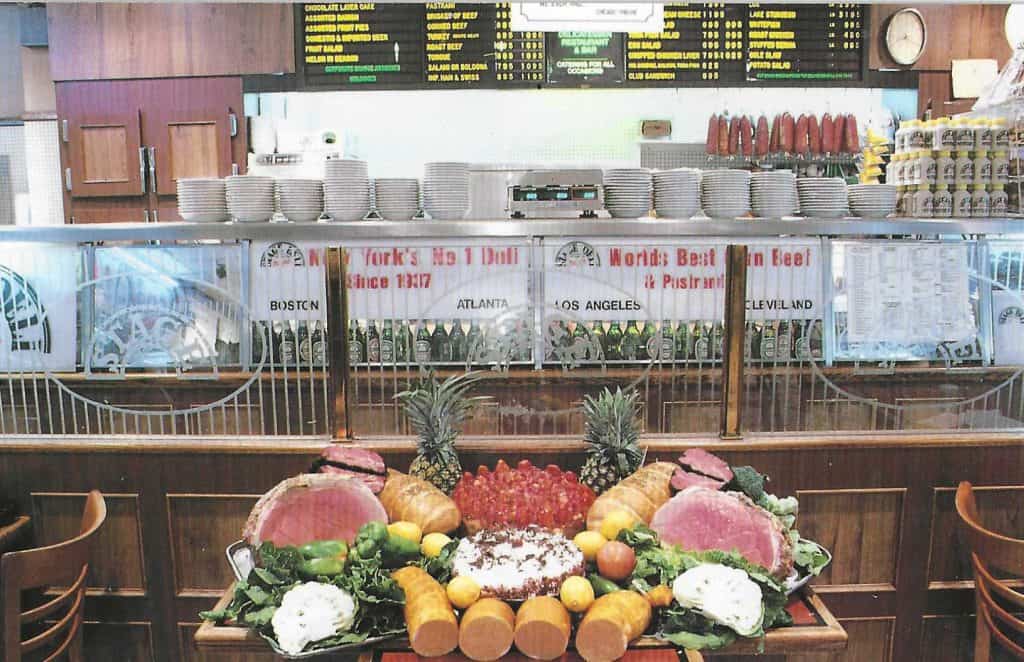

The third variety probably became the best-known type of Jewish eatery after the 1960s, is the deli or delicatessen. Known primarily for ultra-proportioned sandwiches featuring pastrami (cured brisket), corned beef, roast beef, turkey, salami, bologna (pronounced “baloney”), tongue, and chopped liver. Sandwiches are served on rolls – “club” (resembles a small Italian bread,) “Kaiser” (round and sectioned roll,) or a bagel (boiled and baked with a hole in the center) of various flavors. The breads offered are usually rye, pumpernickel (dark, molasses-infused rye) or Challah (double-kneaded egg-twist – the “ch” is a guttural, not pronounced like “cheese.”) Please never ask for a sandwich to be served on white bread; it will make the kitchen erupt in laughter.

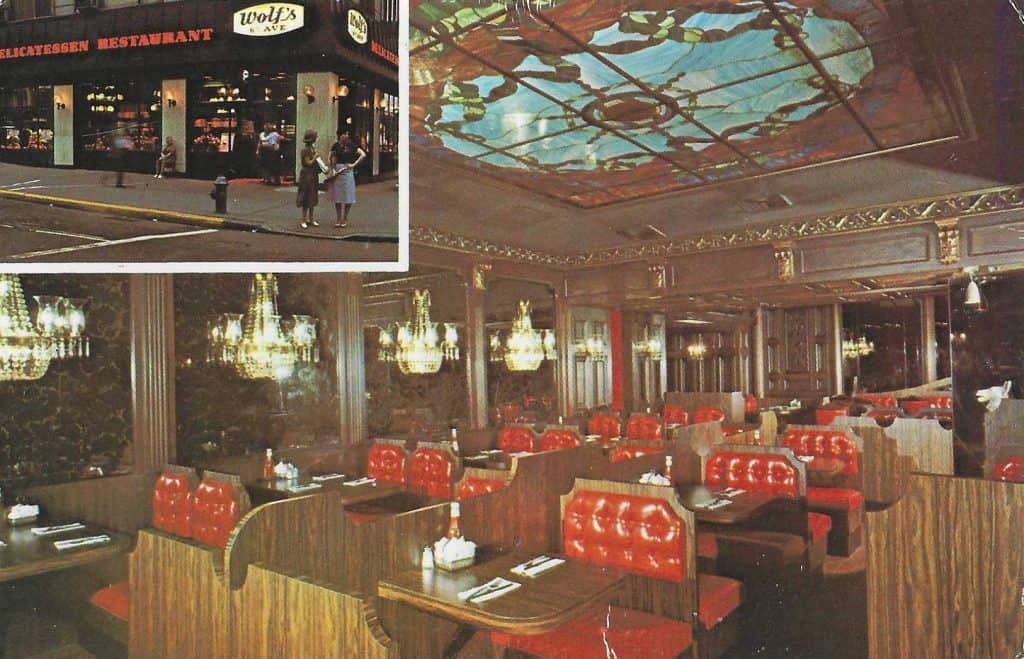

Each of New York’s delis attracted a following and rivalries developed. None of the business competitions were more fervent than the one that existed among the delicatessens located in the Times Square theater district – Wolf’s, the Stage Delicatessen, and The Carnegie Deli. Each was known for its celebrity following and appearance in iconic New York movies, such as Woody Allen’s 1984 hit Broadway Danny Rose.

Each of these Broadway landmarks is gone now but everyone still has favorites that are holdouts. One of my own go-to places is Sarge’s over on 3rd Avenue in Midtown Manhattan. Back in the Day, this deli had a 24×7 policy that attracted club hounds looking for some respite from disco delirium with some matzoh ball soup as the dawn’s early lights were hitting the New York pavement.

Those all-nighters are deep in my past, but I can’t help stopping by for a nosh nowadays when I’m on my way to the Hampton’s Jitney after a visit to my cardiologist at NYU Langone.

**

The author is grateful for assistance provided by Jonathan Freeman and Rabbi Berel Lerman, who reminded me that nearly all restaurants that claim to be kosher today are likely to be so because of legal enforcement.

Another great article by Dr. Mariampolski.

My first taste of kosher cooking was in1962 for my fraternity induction at Phil Gluckstern’s. I had never had such bland food, and this experience has been repeated time and again. Sarge’s doesn’t come close to Katz’s. Sorry if I’ve treaded on anyone’s toes.

This is such an interesting topic especially for someone who only knows NY from the movies or detective series on TV.

You a true sense of the Jewish heart of NY. This would make for a wonderful zoom presentation. I am convinced it would get a good audience and people going down memory lane. Has there been any literature written about the subject?

TY Dr Mariampolski for this great article I shall be in touch.

I meant to say you ‘get a true sense’

An excellent article. Do you know the book, Save the Deli by David Sax (Houghton Mifflin 2009)?

There seems to be a whole genre of Deli Studies to which my friend Mark Federman recently added his own history of Russ and Daughters. A good place to start is an excellent study in the cultural history of Jewish food – Hungering for America: Italian, Irish, and Jewish Foodways in the Age of Migration by Hasia R. Diner which provides the context of immigration and comparisons with Irish and Italian cuisines.

Thank you for the great article; though it does make me hungry.

It’s not just kosher laws that does not consider fish to be meat. Catholics share that quirk and I understand that some Brahmins in eastern and southwest India consider fish to be vegetables from the sea.

A very illuminating article with details about kosher food I wasn’t aware of. Wish I could live in NYC and visit the restaurants you describe. I did enjoy Leo’s Delicatessen in Charlotte NC when I was an adolescent, but that wonderful restaurant is unfortunately long gone.

Hy, a fantastic article. YOU MUST DO A BOOK ON KOSHER DELIS AND RESTAURANTS. GOD BLESS YOU. BOB D.

I remember first learning about “kosher” when I noticed the word on a package of Choo Choo Wheels, a pasta product available in and around Cleveland, Ohio.