In a shoebox atop my office bookcase, I rediscovered a 10-piece set of postcards that show reproduction images of old newspaper advertisements for bicycles. These bicycle ads are amusing from many points of view, especially financial ones. During a recent visit to a sporting goods store in my hometown, I walked by a display of bicycles. The one that caught my eye was a 26” starter version of what was once called a mountain bike – the price tag hanging from the handlebar read $199.99. I did not attempt a thorough examination, but the prices ranged from just over one hundred dollars to nearly one thousand dollars.

The highest price of all the bicycles advertised on these 1898 postcards was $75.00.

[In 1898, the average wage for a US working-class household was between $1.50 to $2.50 per day for skilled laborers. A teacher at that time made about $50 per month. But remember a loaf of bread at that time was 5 cents, and the first Ford model T was still nearly a decade away, but even then, the price was but $780.]

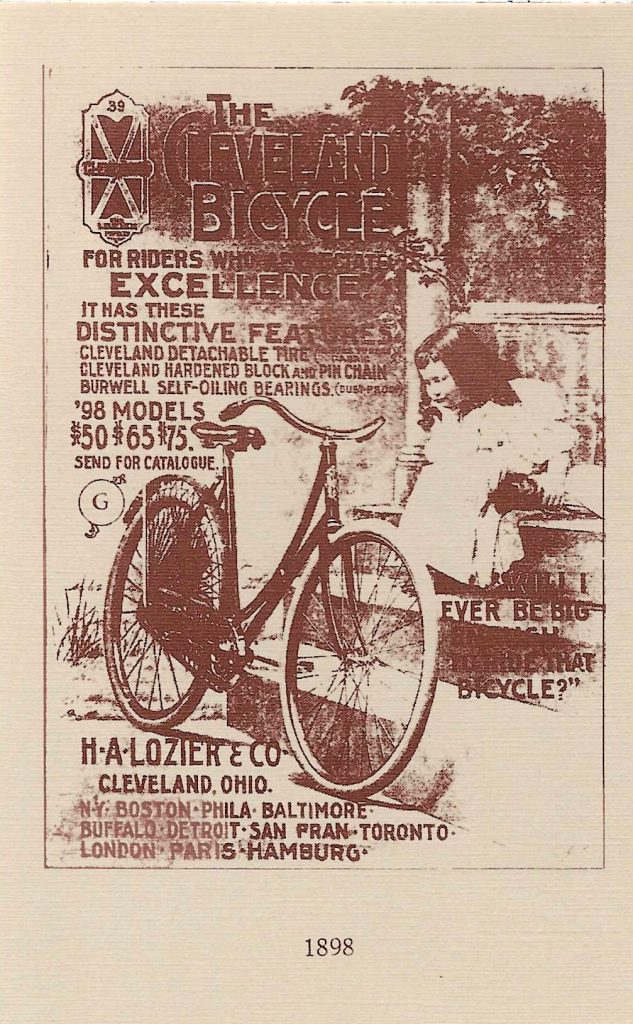

The Cleveland Bicycle was the most frequently advertised. It was for the rider who appreciates EXCELLENCE. The little girl in the ad asks herself, “Will I ever be big enough to ride that bicycle?”

The “Cleveland” was available in both men’s and ladies’ models and had self-oiling bearings. It was manufactured by H. A. Lozier Company of Cleveland. Their other outlet sites were in New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Toronto, London, Paris, Hamburg and other cities worldwide.

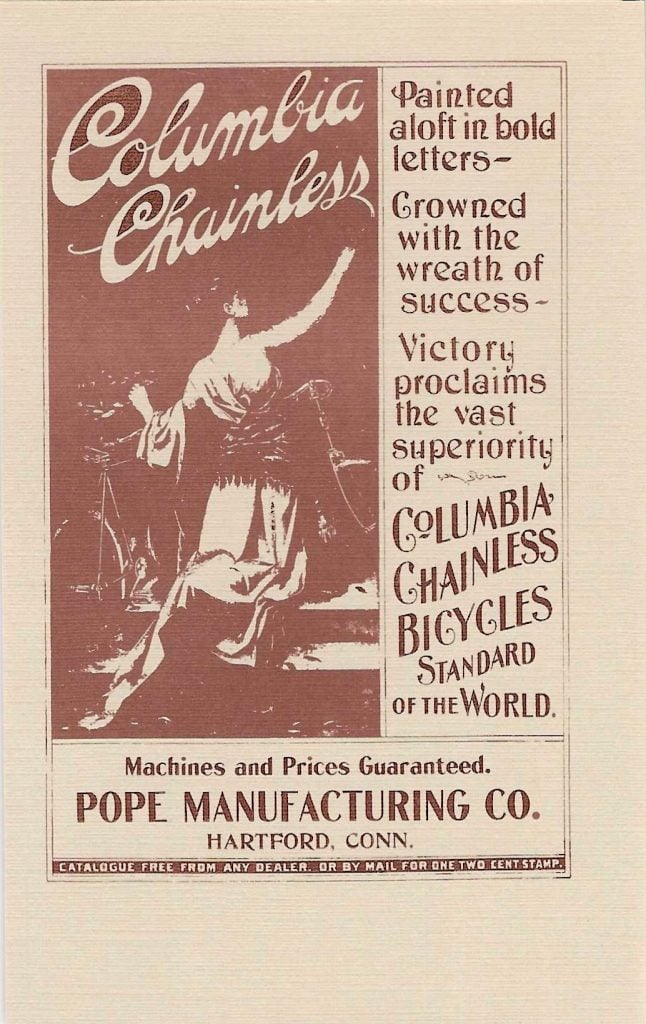

Equally as popular was the Columbia Chainless bicycle that the manufacturers claimed was “Crowned with the wreath of Success.” The machines and prices were guaranteed by the Pope Manufacturing Company in Hartford, Connecticut. Most shoppers thought that the chainless bicycle was a “lady’s” wheel, because the top tube was always set on a diagonal.

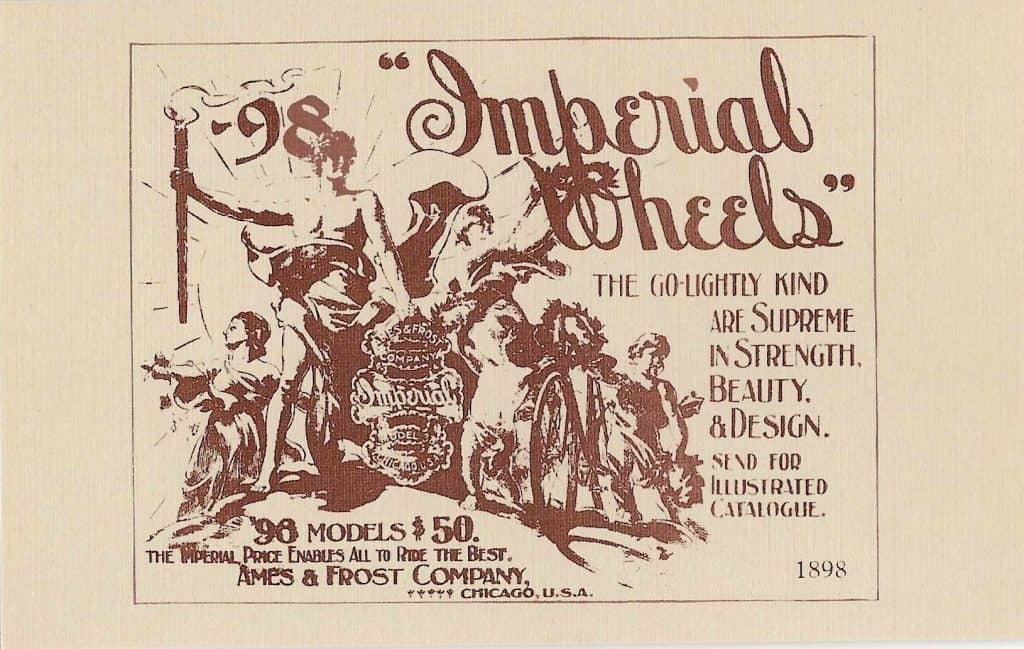

Ames & Frost Company manufactured some of the most durable bicycles ever. William F. Moody of Chicago was granted a patent for a dovetailing machine in 1873. His design was picked up by Charles Ames and Abel Frost and by 1876 their newest product – the Imperial Wheel – was in full production.

According to Ames & Frost’s 1891 catalogue, their new bicycle line was not an experiment since they had manufactured it for fifteen years. They used imported spokes, the best English seamless steel tubing, hubs of superior gun metal, and castings made of aluminum.

A new campaign was launched in 1898 for their 1898 “Imperial Wheels” after a well-advertised trial done by the U. S. Army. In June 1897, the US Army used Ames & Frost’s bicycles for a military exercise that consisted of a 1,900-mile ride across country from Montana to St Louis. It was the only maneuver of its kind and the public response was staggering.

The campaign apparently concluded with newspaper adverts for the [18] ’98 Imperial Wheel” that sold for $50 which enabled “All to Ride the Best.”

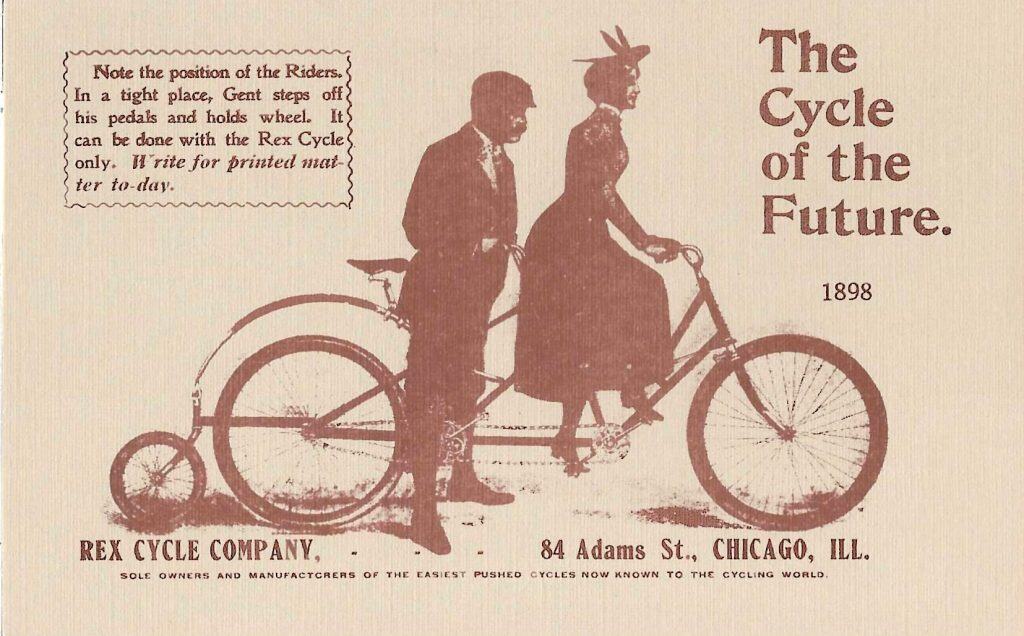

The Rex Cycle Company on Adams Street in Chicago had the most surprising advertisement. It was called, “The Cycle of the Future.” It was a cleverly designed tandem for a man and a woman that had a diagonal top-tube in the front for ease-of-mounting for a lady and a more horizontal top-tube in the back for the gentleman.

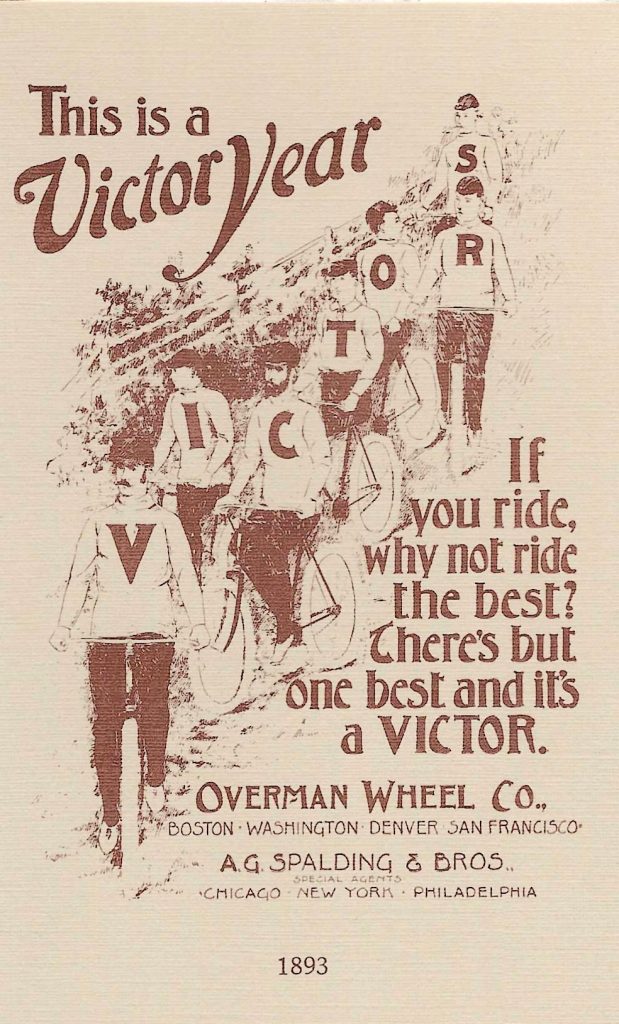

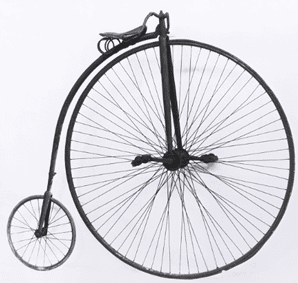

The card that represented the short-lived Overman Wheel Company’s advertisement did not feature a specific bicycle. Overman was originally a Connecticut concern but moved to Massachusetts to avoid state manufacturing taxes. For a period of about twenty years, they built Victor bicycles. First there was one of the most popular bicycles of the nineteenth century – the penny farthing or high-wheeler. Later they redesigned cycles with equal sized wheels that were moved by pedals on a crank-arm. It was called a “safety bike.”

The high wheel bicycle had a front wheel with a 62” diameter, a seat above the wheel, and a rear wheel with an 18” diameter. The pedals were attached to the axel of the front wheel.

The only satisfactory image of a Victor high wheel was found in the Smithsonian Institution’s Objects database. Can you imagine my surprise when I read in the object description that the bicycle that now belongs to the Smithsonian’s American History Museum was once “ridden to many racing victories in the late 1880s by Stacy Cassady, of Millville, New Jersey.” Mr. Cassady was described in his 1930 obituary as being a proprietor of a local store and in his early years a professional bicycle rider who won many sizable purses. And that it was donated in 1921 to the museum by E. Hosea Sithens. Mr. Sithens was a well-known resident of my hometown.