The Grand View Ship Hotel

In early 20th century America a drive through the mountain areas of Pennsylvania was an adventure that ensured wondrous scenery, beautiful, panoramic views and worries about your car—would the radiator overheat? Would there be a flat tire? Or, would the auto just give-up in exhaustion. Back then most roads were not paved and in the rural areas there were few amenities. The various peaks in the Allegheny Mountains were all under 3000 feet, but it was still a struggle to drive to the top without the radiator overheating and another struggle going down if the brakes burning out. In the area between Bedford and Pittsburgh a road evolved, which later became known as the Lincoln Highway. Gradually road stands were built at various places near the mountain tops to provide gas, water and tire patches for the car and food and very basic toilet facilities for the humans. These stops were usually near scenic overlooks as these locations themselves encouraged the motorists to stop and make a few purchases.

The footpath to modern roadway process got a boost in 1912 when Pennsylvania brought in earth-moving equipment to rebuild the road with plans to provide a scenic over-look at Bald Knob Summit (or Davy Lewis Outlook, or as it became known—Grandview Point). The road was christened the Lincoln Highway in 1913. The Lincoln Highway started in New York, went across New Jersey and entered Pennsylvania at Morrisville on the Delaware River then on westward. Years later, after some minor reconfigurations that included Atlantic City, New Jersey, it became U.S. Rt. 30.

Herbert Paulson entered Grand View area circa 1926. He and his family were responsible for the creation and development of the Grand View Ship Hotel, a place of which so many postcards were made over the years.

This 1933 Curt Teich postcard places the S. S. Grand View Point Hotel on U.S. 30, 17 miles west of Bedford, Pa.

Paulson was born in Rotterdam, Netherlands on June 8, 1874. In 1906 he brought his wife Maria, known as Mitzi, and their new-born son Walter, plus Mary, an adopted daughter, to America in 1904. Fluent in German and French, he taught himself English during the voyage. The family was complete when Erna was born in 1909. Paulson supported his family with various jobs, mainly in the Pittsburgh area. In 1926 he “constructed a food stand at Grand View Summit, with facilities across the Lincoln Highway for picnics and camping. He knew the famous curve was the place to be, so he put up a sign that said, ‘Grand View Point, 300 yards away.’ He would have built at the curve himself, but there was already a snack stand there run by Charles H. Richeliew. Before long, however, Paulson had bought the stand at the curve.”

In 1927, Herbert’s first year there, he rebuilt the wall with two small castle towers at the ends and four at an opening in the middle. His new stand nevertheless was still tiny; Paulson did not waste time. The following year he replaced the stand with a large castle-themed building with turrets on the roof and four floors, three on them below road level. The restaurant was now open twenty-four hours and featured chicken and waffles, a German specialty of chicken and mashed potatoes on a waffle covered with gravy.

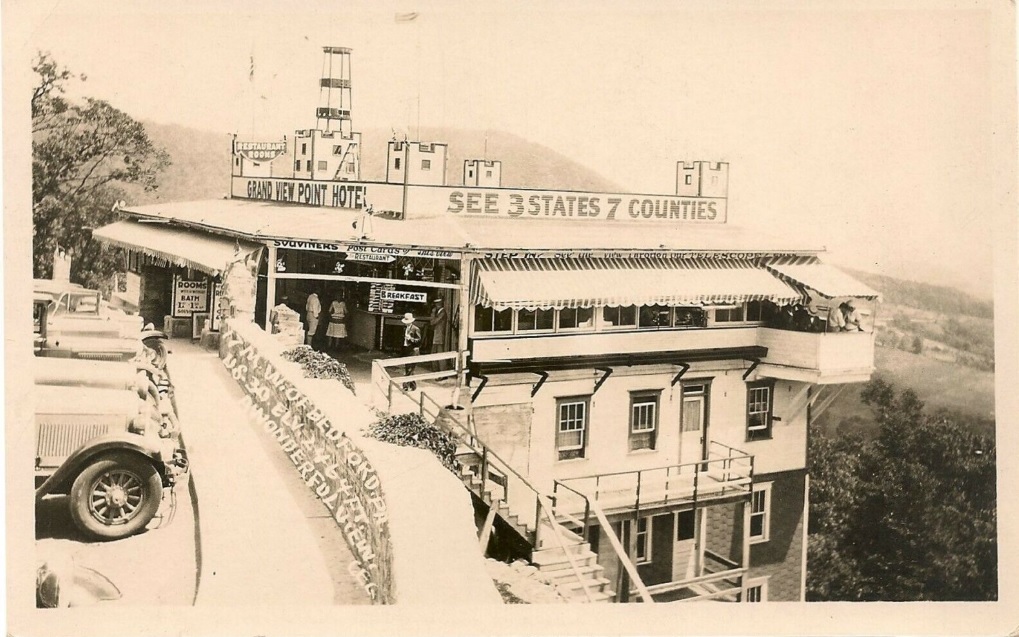

This early real photo card shows Mr. Paulson’s hotel while it was still a castle, and tells the visitors that they can see three states & seven counties

The new structure had a dining room, kitchen and gift shop at road level, with the rooms all having large windows for enjoying the view. The next two floors down had rooms for overnight guests with rates starting at $1 per night. The first basement level had five rooms without bathrooms and one suite of two rooms with a bathroom between. The next level down had four rooms without baths and another suite of two rooms with connecting bathroom. There were also toilet facilities on this level, accessible to all the overnight guests as well as the tourists who could use an outside stairway to walk down. The bottom level contained the furnace and other storage facilities.

Across the road was a gas station with a matching turret on top. Besides gas, many motorists needed water for their overheated radiators. Initially free, a bucketful of water soon became a five-cent purchase. In 1929, Paulson received a permit from the state to install a one-inch pipe to the creek which was 2,800 feet away. This was installed at an opportune time as 1930 was an extremely dry summer.

In his book, The Ship Hotel: A Grand View along the Lincoln Highway, Brian Butko writes, “Paulson realized an even bigger building was needed. It’s been said that he considered shaping the hotel into a fish, as programmatic buildings, such as coffeepot restaurants and wigwam cabins, were all the rage. He obviously liked castles and thought of expanding that idea, but anything too large would have blocked a great deal of the view that attracted drivers to stop in the first place. Paulson was prospering enough to make visits to Europe every two years. Obviously his love of the sea influenced what would become the Ship, but he said the inspiration came while he was camping at Grand View Summit: ‘I watched the fog roll in and how it resembled the motion of the tides.’ And a boat could have tapered ends, blocking less of the view.”

Work on the Ship began in October 1931 on the design by architect Albert Sinnhuber. The architect also supervised the construction which was scheduled to be completed by Memorial Day 1932—a scant eight months later. “Three steel I-beams had been buried in concrete under the roadway curve when it was widened and connected to the building. ‘The state was afraid it would slide,’ Walter recalled, ‘but my father told them, “It’s my property. Either you let me build it or you buy the property.”’ Eighteen steel piers were sunk thirty feet into the rock to keep things from sliding, and twenty-two car frames were added to the concrete foundation for strength. The exterior was covered in three-quarter inch wood, then, overlaid with one-sixteenth inch metal siding processed from the body panels of junked autos. A bow and stern extended the Ship to 120 feet in length, and with the addition of an upper floor, the Grand View Point Hotel was now 42,000 square feet and five stories.”

This 1933 Curt Teich postcard features a Lincoln Highway information sign denoting an elevation of 2,464 feet

At the end of eight months, a grand Memorial Day of activities opened the new Grand View Point Hotel. From noon until far into the night—the music played, the ship was christened and ‘Captain’ Paulson reigned supreme. With the expanded building it began to operate like a ship as well as look like one. On the bow was a captain’s wheel, floating compass and bridge telegraph. Life preservers hung on the walls inside and were mounted on the metal railings on the exterior areas. The crew drilled three times a day and also held inspection tours. Staterooms on the upper level were available at $2 a room or $4 for a room with private bath. The Paulson family lived in a three-room suite in the front toward the bow. The rooms further down, below the main floor, were called the second-class rooms. Employees lived another floor down in dorm-type rooms jokingly referred to as steerage. On the very bottom floor was the coal furnace.

Entering the main doorway, the gift shop was to the right. Additionally a first-class dining room for banquets and parties, as well as a small private dining room were all available.

Water was always a major problem and with the new ship building an 800 foot well was drilled and water was also pumped from a creek a half mile away. As a result there were coin boxes on the toilets which generated a few complaints from patrons.

“The ship was remodeled five times. The biggest change came in the late 1930s, when the bar, soda fountain, and small kitchen prep-room were removed and the outside front pillars were closed in to made room for the Coral Room cocktail lounge. New Wurlitzer “bubbler” jukeboxes were installed in the lounge and dining room in 1939. A room with running water was $3 to $4, a double for $4 to $6 and a double with private bath for $6 to $7. Breakfast cost 30 cents and up, lunch was one-dollar and up, and dinners started at $1.85.”

This early chrome card shows the cocktail lounge. Notice the Wurlitzer jukebox in the corner.

The 1940s were a difficult time for the ship and the family. Paulson was rumored to be communicating with the Nazis via shortwave radio, although his son Walter was serving in the US Marines at the time. But rumors, especially during wartime, were greatly magnified and believed, no matter how preposterous. The Pennsylvania Turnpike was built and opened in 1939, but not widely used by the average motorist until after the war ended in 1945 when gas became available and no longer rationed. The turnpike went from Carlisle, near Harrisburg, to Irwin, near Pittsburgh. It cut three hours off the 160-mile trip by being a limited access highway with gentle grades and curves. By by-passing towns and building tunnels through mountains, this four-lane highway became the model for many other toll roads built during the next decades. Business declined at the Ship.

Mrs. Paulson, Mitzi, suffered from severe arthritis, but continued to sit at the front desk every day. Herbert Paulson suffered a heart attack and went to live with his daughter Mary in Virginia for a while. Management was turned over to the children Erna and Walter. Mitzi passed away January 1, 1966. Herbert returned each summer and in 1973 fell and died in a bathtub in his beloved Ship. He was 99.

Finally in October 1978 the Ship and two acres were sold to Jack and Mary Loya for $37,000, along with seventy-five adjoining acres for $40,000. The Ship had an extremely run-down appearance with rust appearing on the metal covering. The new owners covered the exterior with hemlock boards coated in creosote, repainted and cleaned-up the interior, removed the smokestacks and renamed the vessel Noah’s Ark. Across the road a petting zoo was established with animals from the defunct Leonard Kiser’s Wildlife Ranch in nearby Central City. Rooms for the night ran $15 to $25. The dinner menu included southern fried chicken for $4.95 and ice cream sundaes for $1.25. But no matter how hard they tried, the Loyas could not sustain a profit. A few animals died and they sold the rest. They tried adding a ski lodge but that didn’t help. Finally in 1987 they sold it to truck driver Ron Overly and his fiancée, Christine Ford. It was listed on the National Register of Historical Places in 1997 but the new owners were having great difficulties in meeting mortgage payments, vandals were breaking in and removing things and business declined. Eventually the property reverted back to Jack and Mary Loya.

In 1995 the Lincoln Highway Heritage Corridor identified the cost of rehab at $2.9 million and looked for sources of money to restore the building. Jack Loya and his son Landon put on a new roof in July 2001, but disaster struck in the early hours of Friday, October 26, 2001. Nine fire companies responded to the fire. Wind spread flames to the surrounding trees and the firemen were unable to contain the fire to the building. About an acre and a half was destroyed. Loya did not have fire insurance and still owed on the mortgage. The cause of the fire was very suspicious and eight days later two other abandoned roadhouses on the Lincoln Highway were also torched. In all, a sad end to a memorable building.

Excellent article! I first passed this circa 1998 when touring that part of the USA (I live in the UK) and stopped to look closer the following year. It was a shame to see it looking the worse for wear and I was very sorry indeed when I heard it had burned down.