Bridget Whittle

Identifying Real Photo Postcards

Using Crowdsourcing

Train wreck near Rivers, Manitoba, 1921

In 2008, McMaster University’s Archives and Research Collections received 4,021 postcards from a private collector. The cards were scanned in anticipation of an online exhibit, but funding failed to materialize and the scans languished on a server. Meanwhile, the physical postcards were filed by Canadian province or country and shelved.

A general description of the collection was put online, but almost no one used it. Filing physical postcards by region often did not help researchers who wanted information from the message side of the card. This arrangement scheme served some collectors, but most were unaware of our collection or felt they were not allowed to access the archives to see it. The digital scans could have made access much easier, except they had no information on them – not a place, no date, nothing, even if this content was written on the card. In short, we had all of these great postcards and almost no one could use them.

Could Crowdsourcing Be the Answer? The idea behind crowdsourcing is if you ask lots of people to contribute information or perform a task instead of having a single person do the same job, it will be completed much faster. In September 2015, we put all the images of the postcards online and invited people to contribute as many or as few descriptions to the cards as they wanted.

If possible, they were asked to give the location, the date, a general description of the image, as well as the message and any other details that seemed appropriate. In many cases the basic information was clearly written on the card, but because it was not readable by the computer, it was as good as unidentified.

Cards like this could be quickly and accurately identified by anyone who was interested. Other cards required more digging and many different people, from postcard collectors to nautical historians, provided their expertise to identify the cards.

“Wager to Walk around the World” portrait of Harry Bensley and Mr. Allen, United Kingdom, 1908.

After a year, there were 12,000 descriptions, which meant that some postcards had been looked at by two or three people, and others by as many as ten people. In one year, we had accomplished what we had been unable to do in the previous seven. All that remained was to clean up the data, standardize information, and combine descriptions so that they all made sense. Almost three years in, crowdsourcing is proving to be a valuable tool, but not without its problems.

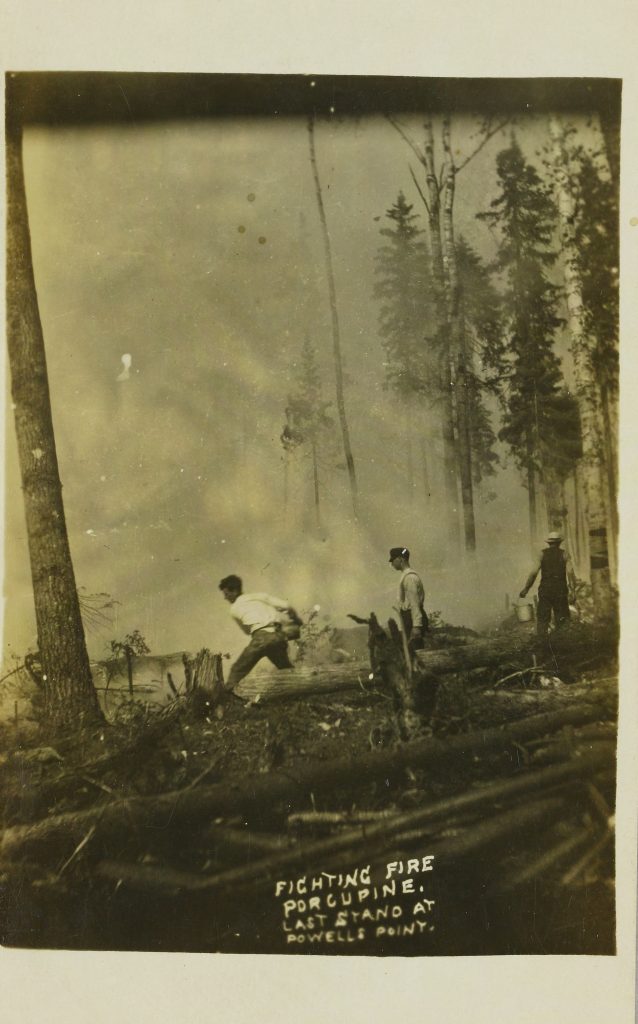

Fighting Fire, Porcupine, Last Stand at Powells Point, 1911.

The Downside of Crowdsourcing. There is a lot of information on a postcard, from multiple dates to publishers or photographers, as well as the price from the modern dealer. At the beginning of the project it was hard to know all of the things that volunteers might include and make rules about how to standardize this information.

A good example of this is how place names change over time. What do you do with a postcard of Berlin, Ontario, given that it was renamed Kitchener during the First World War, or Port Arthur and Fort William, which are now the single city of Thunder Bay? The postcard says one thing, but modern day searchers might be looking for it a different way. Volunteers identified some of these dilemmas, while others had no idea.

As the clean-up work progresses, we are recording these changes and will apply them to all the postcards that are like this, whether they were identified or not.

In other cases, we received information that was incredibly valuable, but there are better ways to present it. For instance, many people took the time to supply a link to google street view of the current scene depicted on the postcard. This information is often very helpful, but there is little guarantee that the link will persist over a long time (how many times have you gone back to a link only to discover that the page is no longer there?). Instead, we are providing standard GPS coordinates of the location. This will allow people to look at it in street view, as well as do many other things with that precise geographical data.

In the end, there is no savings in time. However, there have been other advantages.

Already in Use! Access to the scanned postcards is already so much better. Now, when someone asks for a postcard of a specific place or by a particular photographer, the mass of data can be searched with a few keywords.

And instead of spending hours flipping through the physical cards hoping to find one, the digital image can be located in seconds.

Porcupine Fire, Carrying Out the Dead, 1911.

For example, a researcher recently asked for any cards related to the fire in the mining town of Porcupine, Ontario. Searching on ‘Porcupine’ provided not just images of the town, the fire, and the mines, but also all the messages about the fire, shedding light on the human side of the disaster as well as its visual record.

Worle Harvest Festival, 1912.

Specialists from all over the World. Many of the cards were very straightforward to describe, but there were some that did not have a lot of information. One person describing all of the cards would not necessarily have had the time to hunt for details about every single card. For instance, this card featuring a man on a bicycle had little to identify it. Information on the back suggested it was related to Worle, but who is the man? And what else is going on? Is this a race or a triumphant return home from a long journey?

One amazing volunteer reached out to the Worle Historical Society in Somerset, England, and they were able to identify Eli George as the man on the bicycle, that this was the yearly Harvest Festival, and who the photographer was. The society itself was delighted with the image. They have some 5,000 photographs, but this was a new one. Not only are the descriptions better, but the postcards were linked back to others who can use them too.

Forward from Here. Crowdsourcing has brought attention to an underused collection. The descriptions have helped the collection over the first hurdle and staff time has been allocated to finish the clean-up work. By the end of 2020, the postcards will be available in person and online in a searchable database for everyone to use.

Very interesting history!

Hello, all! I am currently blogging on a site entitled The Collation, managed by the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C. The blog title is Postcards in the Folger Archives. In a previous life, I produced three books on vintage picture postcards in three countries on three continents: (French) Guinea in West Africa, Indonesia in Southeast Asia, and El Salvador in Central America. I look forward to following the discussion.

Very interesting! It is amazing how people can solve a mystery! Are all the cards you have believed to be Canadian?

Hi Lynn, we believe about 2/3rds of them are Canadian and the remaining 1/3 are International. Once the information is cleaned up, it’ll be a lot easier to get these sorts of stats too! I’m glad you enjoyed the article, and my apologies for the delay in getting back to you, the article came out while I was away.

Bridget

Hello Bridget. I just stumbled on this article while looking for something else. Can’t tell you how happy I was to read that work had started again on getting everything on line. I had worried that things would not proceed. Researching those cards was such a wonderful experience. Take care.

Are your postcards available to view on-line?

Could a private collector like myself use Crowdfunding (once I learn how to use it) to identify RPPC’s in my collection?

Did you mean to say “crowdfunding”, instead of “Crowdsourcing”? Also, there are Facebook groups that help identify RPPCs: https://www.facebook.com/groups/rppcmystery/

I’m reading this in 2022, so I can provide a link to the collection: http://digitalarchive.mcmaster.ca/islandora/object/macrepo%3A94048