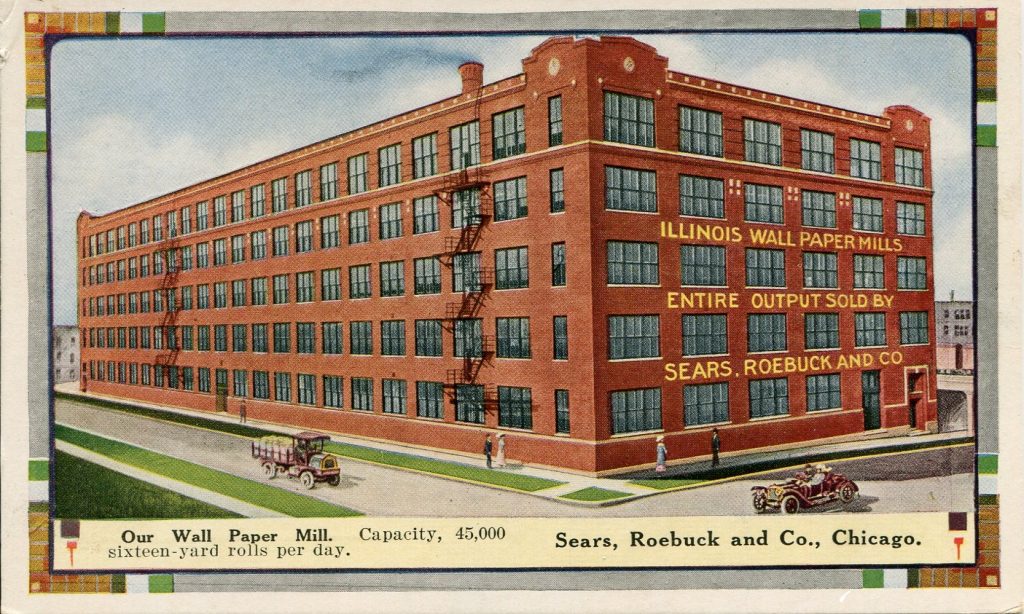

Sears, Roebuck and Co., Chicago

An aunt of mine changed the wallpaper in her kitchen twice a year. It usually happened just before Christmas and around the Fourth of July. My uncle supervised; I assisted. My job was to put the paste on the paper and accordion fold it for easier handling. The fold – wet-side to wet-side – made it possible that when the top edge was situated into the meeting of the wall and the ceiling the “package” would drop-open down the wall and need only a soft brushing from the center to the edges to be in place.

The paper used in those days (the 1940s & ‘50s) cost 40¢ to 65¢ per roll. (Paper hangers call a piece of wallpaper (at its manufactured width) long enough to cover a wall from top to bottom, a page.) Each roll of paper was long enough to get three pages. The first page installed would be against a plumbline and each subsequent page would abut against the previous.

The Sears, Roebuck store where the new wallpaper was purchased was about six miles away. I was only asked to go-alone on one trip to buy wallpaper, and I never know why until many years later. My aunt told me it was because I spoke-up about which papers I liked and those were always much more expensive than my uncle wanted to spend.

It most likely never occurred to me, as a young boy, that someone had to make the wallpaper we put on the kitchen walls. Epiphany may not be the right word, but one day during a family vacation in Williamsburg, Virginia, I heard a tour guide talk about the hand painted wallpaper in one of the historical houses. That instant, I wanted to see wallpaper production in person.

The idea of wall beautification developed in Europe in the first and second decades of the 16th century. For those who could afford such a luxury, tapestry, tile, stucco, and plaster topped the list of options, but by the mid-18th century wallpaper was the most favored.

When the use of wallpaper came to colonial American, several small manufacturers in New England and Pennsylvania developed distinctly American designs and the public quickly broadened their interests and embraced their unique patterns.

By the 19th century the American wallpaper industry centered in Chicago, Illinois. One reason being that Sears, Roebuck had recently reconfigured their business model and began manufacturing their own brands. We all remember Kenmore and Craftsman. As the popularity of wallpaper grew so did the Sears, brand-named papers: York, Brewster, Wallquest and Chesapeake among them.

Through the decades paper popularity has ebbed and waned for a variety of reasons; cost, ease of cleaning and seasonal décor changes have influenced decoration choices.

My aunt certainly cared little about who made her wallpaper, but she was a loyal customer of Sears, Roebuck when a roll cost so little. The sticker-shock buyers experience today when some papers cost more than $100 per roll might account for the current lack of interest. It could be that my aunt once saw the postcard above and learned that Chicago was where her wallpaper was made.

For you readers who have a deeper interest there are museums on three continents that have extensive historical wallpaper collections.

- The French Decorative Arts Museum in Paris

- The German Tapetenmuseum in Kassel

- The Historic New England Museum at the Otis House in Boston

- Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires

- The Smithsonian, Cooper-Hewitt Museum in New York City

- The Victoria and Albert Museum in London

- Winterthur Museum in Winterthur, Delaware