Bob Toal

Carving Stone Mountain

While in college at Athens, Georgia, during the 1970s, I toured Stone Mountain several times. It is an impressive bas relief sculpture depicting Confederates Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and Stonewall Jackson astride their horses; Blackjack, Traveller, and Little Sorrel.

Stone Mountain has a complex and controversial background. Started in 1916, after three starts by three different sculptors and a 36-year hiatus, it was finished in 1972. In various times postcards and folders show it in various stages of planning using proposed designs that never materialized, in stages of development and at completion. An historic overview follows.

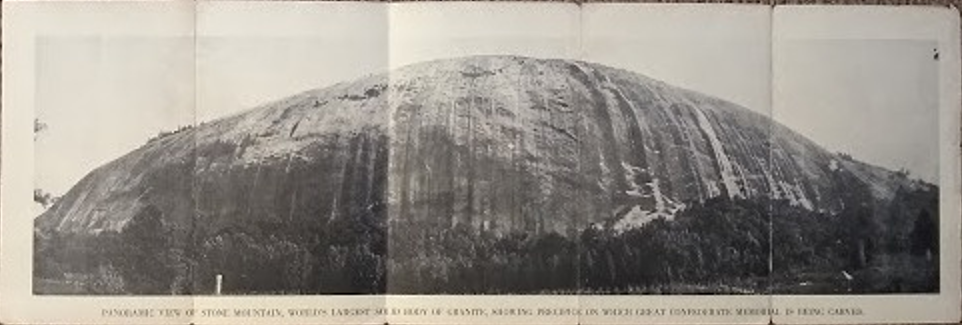

Early postcards show Stone Mountain as a natural wonder, 16 miles east of Atlanta, Georgia. The granite mountain rises 825 feet and is four miles in circumference. Its north face is a shear drop. The village at the base burned during the 1864 Battle of Atlanta, as naked chimneys in the foreground show. The mountain became a granite quarry in the 1830s and with arrival of a railroad spur, quarrying boomed. The mountain was bought in 1887 by the Venable brothers [William Hoyt Venable (1852–1905) and Samuel Hoyt Venable (1856–1939)]. They quarried it for 24 years then rented it out to Stone Mountain Granite Company. Stone Mountain granite was used in the construction of the Panama Canal, the Capitol’s east wing steps and the Lincoln Memorial foundation and other sites. The Venable family sold the site to the state in 1958.

In the 50th anniversary years of the Civil War (1911-1916) sectional animosities were dying out. Veterans and families from the north and the south, eager to commemorate their service, erected monuments and statues. Who first conceived the idea of a Stone Mountain confederate soldier memorial is unsure. An 1869 poem by Georgian physician-poet Francis Tichnor entitled Stone Mountain is first to allude to a carved monument on the mountain to Alexander Stephens, the former Vice President of the Confederacy.

Alternatively, it is said a monument on Stone Mountain to Robert E. Lee was first proposed by Helen Plane in 1909. Her husband who served with Lee was killed at the Battle of Sharpsburg (Antietam) in 1862. Mrs. Plane was the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) Atlanta Chapter president. She began vigorously promoting the idea after reading Atlanta newspaper editorials by William Terrell and John Temple Graves in May and June 1914 that suggested carving a memorial on Stone Mountain that would honor the men of the Confederacy. It was said that Union soldiers had Decoration Day, but Southern soldiers were forgotten. Discussions with Sam Venable followed. He was supportive of Plane’s idea and gave a go-ahead with one stipulation: the carving was to be completed within 12 years after a sculptor was chosen.

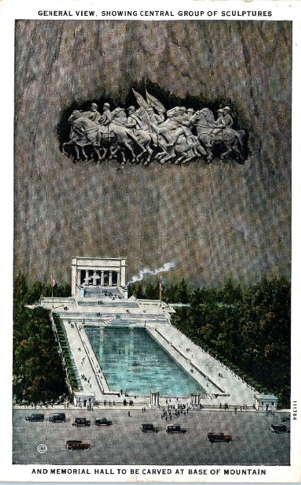

Gutzon Borglum, of Mount Rushmore fame, was contacted by the UDC (Plane) in June 1915. During a visit to Stone Mountain that August, Borglum dissuaded Plane from a simple large bust carving of Lee. Instead he ultimately proposed carving a panorama covering 1.5 acres involving a central group of figures including Lee on horseback, supported by marching soldiers, horses and artillery. He also proposed plans for a memorial hall at the foot of the mountain with an amphitheater. He estimated a time frame of six to seven years and total cost of $3,500,000. The UDC supported the concept but refused to contribute money.

Borglum then said he could complete the central figures for $250,000. This seemed more realistic as a place to start. Borglum was appointed carving sculptor in May 1916 by the newly formed Stone Mountain Confederate Monument Association with Helen Plane as founder and first president. The Venable family deeded the north face of the mountain to the UDC/SMCMA with the agreed 12 year time limit.

From 1916 to 1917 worksite infrastructure that included 500 feet of plank steps, platforms, rigging, and later electricity, was built on the mountain. Also, fund raising began and design models appeared. Late in this period, World War I and poor funding caused a halt for several years and Borglum got involved with other projects. Plane at age 91, resigned from the SMCMA in 1920 while the project was still on hold. Her low-key replacement lasted three years and then in March 1923 strong willed Hollins Randolph became the new president of SMCMA.

Borglum returned to Stone Mountain in 1921, repaired the infrastructure, and used a giant stereopticon to project an image of his model on the mountain face at night which was painted in outline by workers suspended from cables. Actual carving started June 18, 1923. Pneumatic drills cut 24-inch deep holes into the granite following the painted pattern. Then granite chunks were removed using the plug and feather process. Dynamite was also used but tended to leave cracked granite. A quadrafold postcard published by the SMCMA shows Borglum, his workers, and the proposed design on one side, and the north side of the mountain on the other.

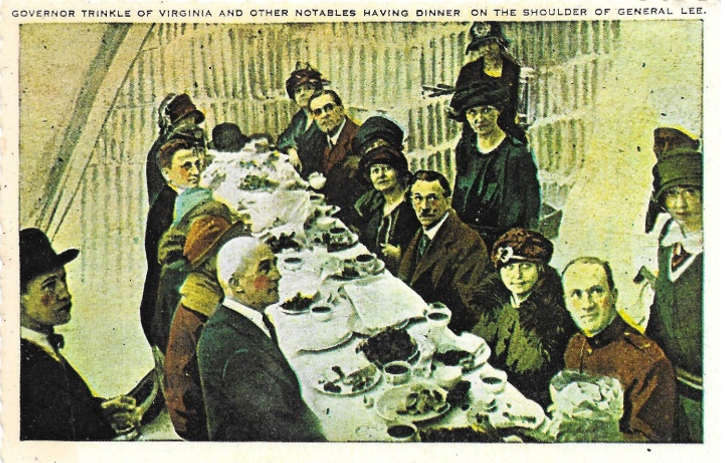

Borglum finished the head and shoulder of Lee in time for an unveiling scheduled for January 19, 1924 – Lee’s birthday. A group of dignitaries including Helen Plane dined on Lee’s shoulder before a ceremony witnessed by 5,000 people. A classic postcard of this event is shown below.

In March 1924, because fund raising was still sluggish, President Coolidge authorized minting up to five million half dollar coins commemorating the soldiers of the South. The coins were to be sold at $1.00 each. The coins generated almost $700,000 over a three-year period but due to questionable management of the SMCMA by Mr. Randolph only about 20% of it went toward the carving.

By early 1925, 60% of the central area for the figures was roughed out but work abruptly ended on February 25th when Borglum was fired by Randolph. Both men had a falling out over the last year. Lack of money for carving was the issue for Borglum and lack of dedication the issue for Randolph. (Borglum had recently visited South Dakota on a consulting mission.) An uproar ensued in the press with Venable and UDC wanting Borglum back, but that was not to be, for he signed a contract on March 9, 1925, to do Mount Rushmore.

Helen Plane the original force for the project died on April 2, 1925, at age 96. Then on April 16, 1925, a second sculptor, Augustus Lukeman, of New York, was hired.

Lukeman’s design ideas were different. His new plan consisted of a group of nine men on horseback. Davis, Lee, and Jackson were closely followed by two color bearers and four other mounted horsemen. The scale of the figures was smaller than that of Borglum. The new carving was started in 1927 below the head of Lee which was in place. Images from this era show Lukeman’s design. It is easily recognizable as it appears as a group of men on horseback with two flags at the center. The idea of a memorial hall at the base was still on the books.

Lukeman hired Stone Mountain Granite Company to oversee the work which he visited from New York monthly. A stone cutter named Theodore Bottimelli, one of Lukeman’s favorites, did the fine carving work. In March 1928 Lukeman dynamited Borglum’s carving of General Lee off the mountain. The SMCMA did not announce their intent beforehand. When information leaked out Sam Venable sued to keep it from happening. Removing Borglum’s work turned out to be a psychological blow to UDC and Sam Venable who were friends of Borglum.

The carving was unveiled to the public April 9, 1928. Lee was finished to the waist, and the head of Jefferson Davis and Traveller blocked out. Hollins Randolph resigned, and an audit showed the poor financial health of the SMCMA. The new president of the organization did his best to smooth things over but could not work out a deal with Venable and the project came to a permanent halt.

Postcards of the post 1928 era show the ghostly remnants of an incomplete image of Lee and Traveller as well as Jefferson Davis and Jackson’s faint outline. Above is scaffolding and a rough imprint of Borglum’s Lee.

Attempts over the years to renew the project failed. It remained silent for 36 years. In 1958 Georgia acquired Stone Mountain and surrounding lands from the Venable family for use as a public park. With state sponsorship and a renewed Stone Mountain Memorial Association, a new lease on life emerged for the sculpture.

Massachusetts artist, Walker Hancock was hired in 1963 as the third sculptor of the project. He proposed his own plan, but officials insisted he complete the work begun by Lukeman. They decided to limit Hancock’s work to the three main images of Davis, Lee and Jackson. Work resumed in July 1964 with a team of seven men using new techniques and tools called jet torches. The new tools proved efficient and controllable in sculpting the figures to the smallest detail.

Among the crew was Roy Faulkner, a welder who was hired to help make the elevator installed for the workers. Faulkner continued as a carver after an accident took part of the crew off the job. He graduated to chief carver without any artistic training and was so efficient that he soon took over the brunt of the carving.

One of the last adjustments made in the design was Jefferson Davis’s hat. The original Lukeman model had Davis with a military style hat, but since he was a civilian, he would not have worn such a hat.

Postcards of this era show the progress in defining the three central figures along with scaffolding in place. Look for postcards of a completed Jefferson Davis with the military style hat (like Lee’s) and one with his new – civilian hat. See below.

Card images from the Hancock era showing Davis and Lee.

This is a detail that is fun to look for in the various cards.

Another dedication was held in 1970, but the work was completed when the granite was smooth and the scaffolding was removed in 1972.

The next time you go to a postcard show spend some time looking at Stone Mountain cards. Knowing its history sheds new light on the topic.

As a Brit I found this to be a very interesting and Informative read 🙂 So many thanks for the article.

Thoroughly enjoyed this article. For anyone thinking about visiting Stone Mountain, I highly recommend the Laser Light Show that is projected onto the side of mountain on nights from Spring – Fall. A very unique experience!

I enjoyed reading your article, very much. Had the opportunity to visit Stone Mountain when it was still being shown as a laser type show making the horses look like they were moving. Beautiful place with history that needs to be protected! I learned a lot more about it by reading your article. Thank you!

Lots of interesting history here. I find the information on the change in Davis’s hat especially memorable.