In a recent (September 2019) Smithsonian Magazine article authored by Amy Crawford, a freelance journalist from Michigan who writes on a wide variety of topics, we find the perfect text to accompany a set of wondrous postcards published in Germany close to nine decades ago.

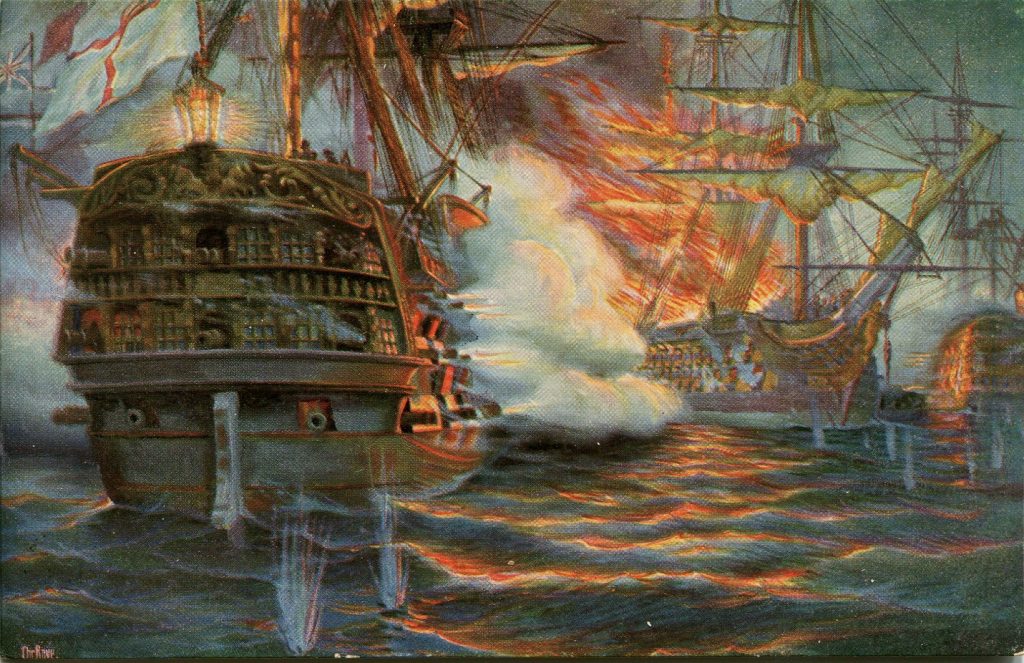

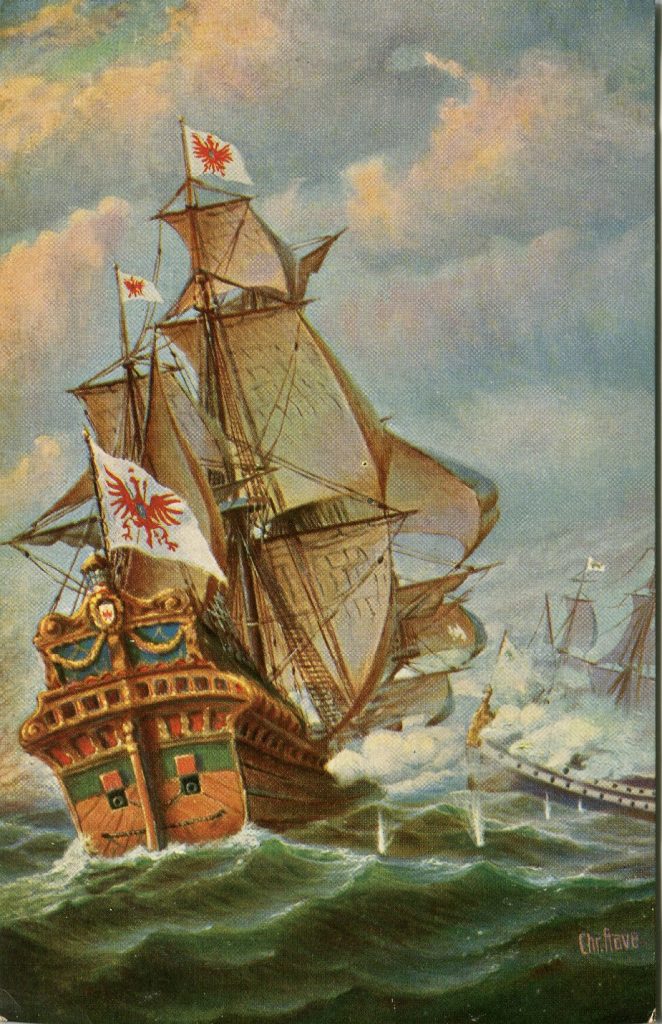

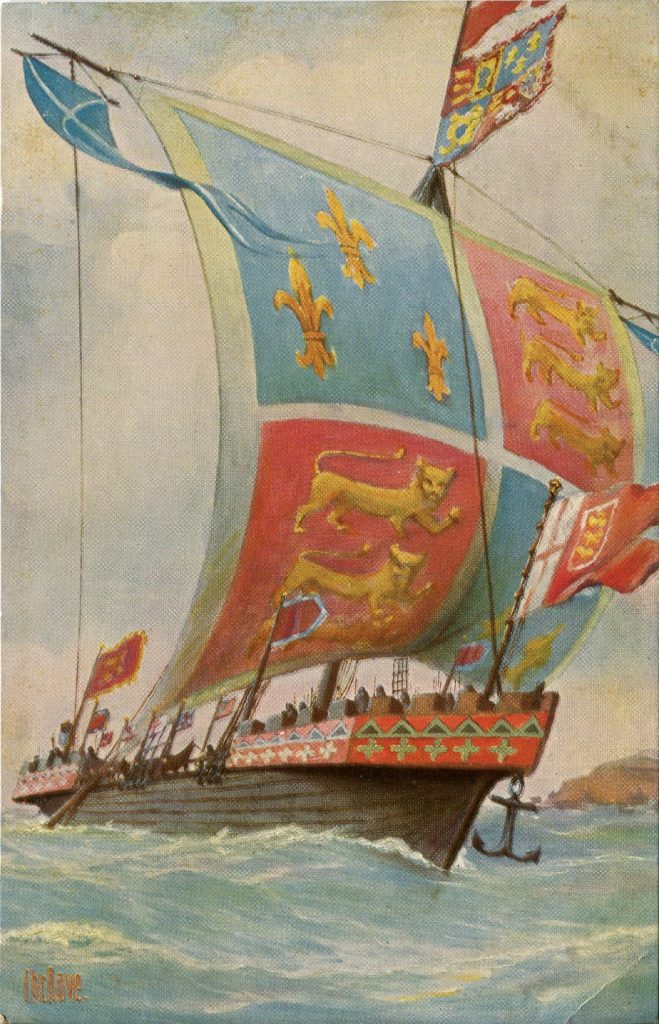

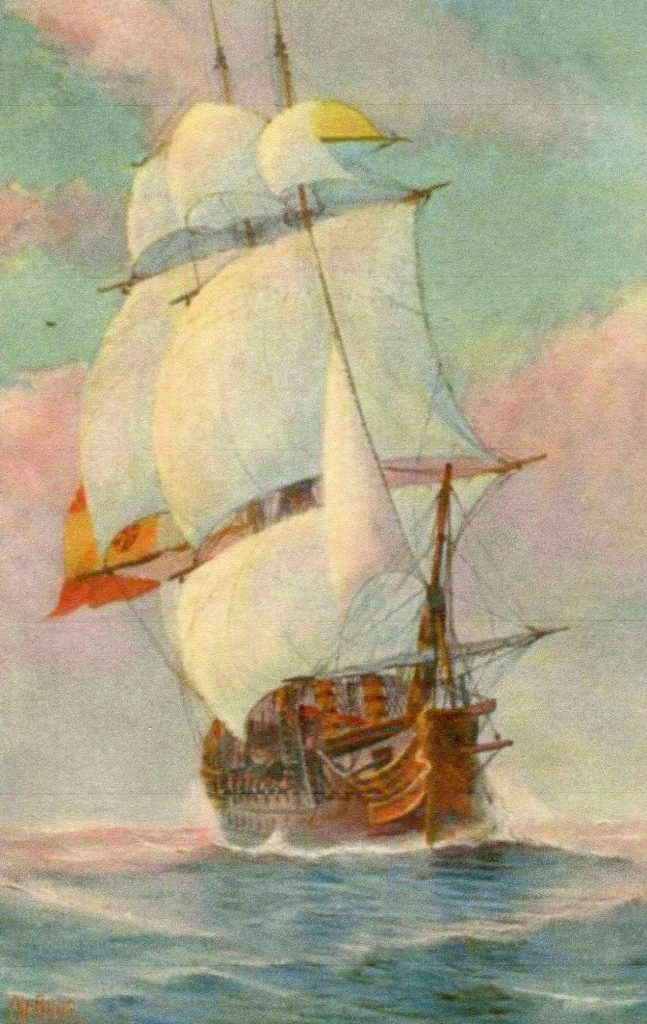

This set of cards is the largest I know about. There are 300 cards in the set, all of which are based on original art held or images acquired by the “Marine-Galerie” in Germany. The variety ranges from Viking long-ships to typical, yet unique Kriegsschiff sailed in the nineteenth century by the English, French, Germans and Spaniards.

Postcard history readers owe it to themselves to find and read the entire article (it is online at Smithsonian.edu), yet I follow this advice with two quotes. Here is where Crawford’s piece picks-up the story:

For four centuries, Spain’s prodigious naval power built an empire that stretched around the globe. But not every military or merchant voyage ended well. In the first analysis of its kind by a former colonial power, Spain’s Ministry of Culture has identified 681 shipwrecks in the Caribbean and along the southern Atlantic coast of the United States. They date from 1492, when Christopher Columbus’ Santa María hit a sandbar near modern-day Haiti, to 1898, when the U.S. Navy sank the Plutón off the coast of Cuba during the Spanish-American War.

Crawford goes on to explain how Carlos Amores, a professional archaeologist has spent five years in a search of Spanish archives to identify vessels lost at sea due to weather and pirates. The reader is also reminded of the tragic loss of life involved in these events.

She continues with:

The ships carried diverse cargoes, from food and weapons to religious objects, but it’s the glittering products of Spain’s New World colonies that have long attracted interest from historians and fortune seekers. Already the government’s unpublished list is being called “the world’s largest treasure map.”

At this point, it is likely that an assumption can be made that this set of postcards may help is some peculiar way to identify at least some of the lost ships. The artistic record may be the only clue available to the courageous men and women who are working to learn more about these mysterious incidents. And, use what they learn to foster an international understanding of how cultures should blend in a congenial balance.

Amy Crawford ends her essay with a simple reminder that, “Each ship that sank between the Old World and the New is evidence of the beginning of globalization.”