Hy Mariampolski

Decoding Yiddish Postcards

Yiddish postcards usually occupy a small section of dealers’ Judaica offerings, but they are redolent with meaning and significance.

Millions of Yiddish postcards were exchanged primarily during Rosh Hashanah, or the Jewish High Holiday season in late summer and early fall, from the 1910s through the 1950s. This was the period of mass migration from countryside to cities and across national boundaries. Yiddish postcards were an important means of keeping families and friends connected regardless of whether they were still living in Russia, Poland, Hungary, and Austria or had immigrated to England, North America or Argentina.

Some explanation about the history of Yiddish would be helpful. Most Americans speak at least a little Yiddish – the common language of daily life spoken by Northern and Eastern European Jews. They learned it from Jewish-American comedians like Mel Brooks, Woody Allen, Larry David, or Adam Sandler and use words like schmuck or schlemiel and schlepp to describe someone who is obnoxious or hapless and a tedious activity.

The Yiddish language is lexically related to German and incorporates bits and pieces of Hebrew, Greek, Slavic and Romance languages. The word schvigger meaning mother-in-law, for example, is derived from the Spanish word suegra. Yiddish is normally written with Hebrew characters, that most traditional Jews learned in their religious education.

Yiddish postcards are interesting not only from a linguistic perspective but also because of the historic and ethnographic details they represent. They show a culture in transition, grappling with the move from traditional village life to 20th century urbane modernism.

Examining a few samples of Yiddish postcards demonstrate the charm and eloquence of this art form.

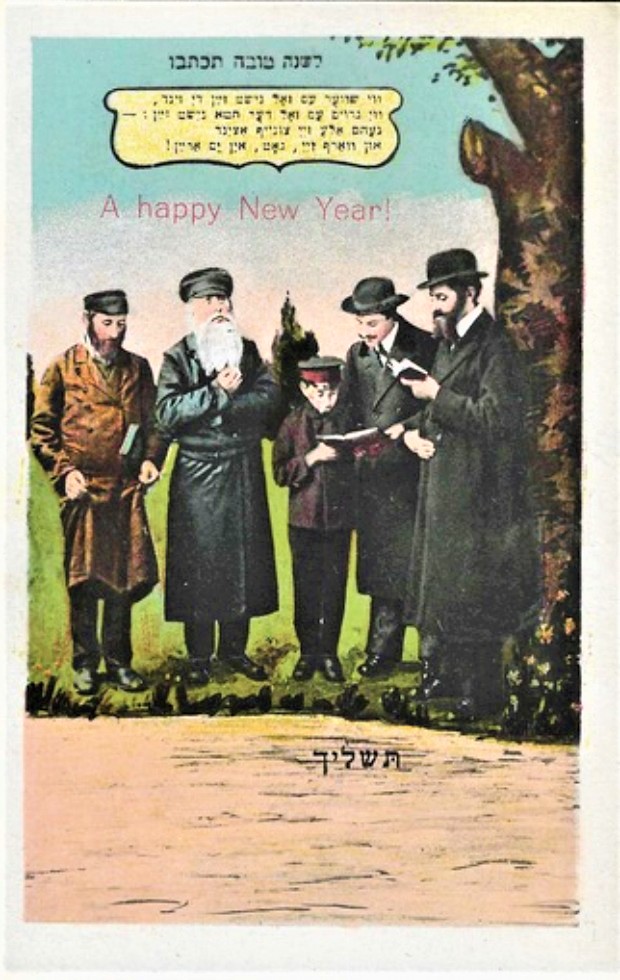

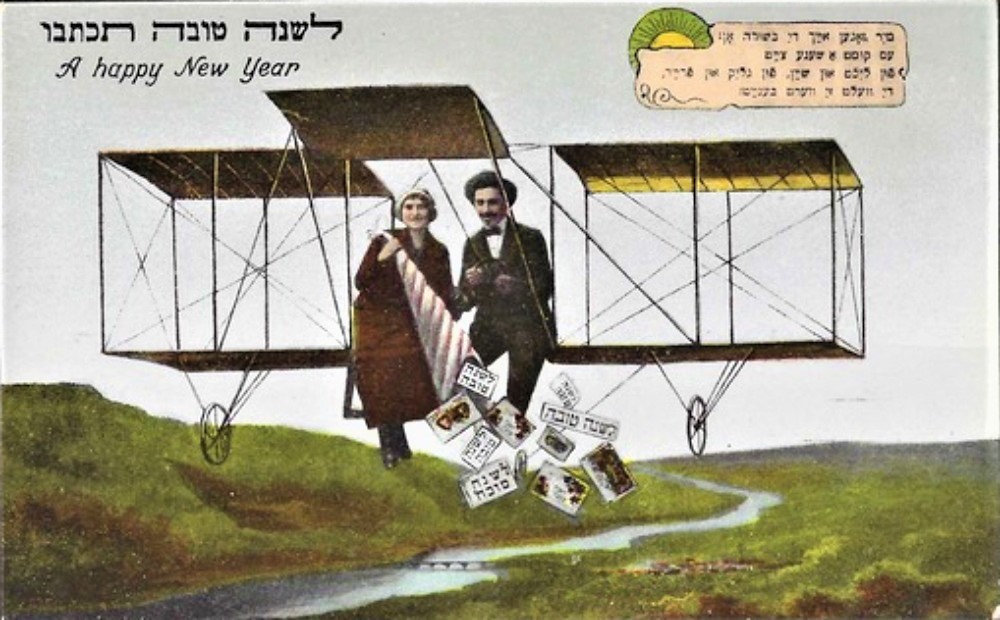

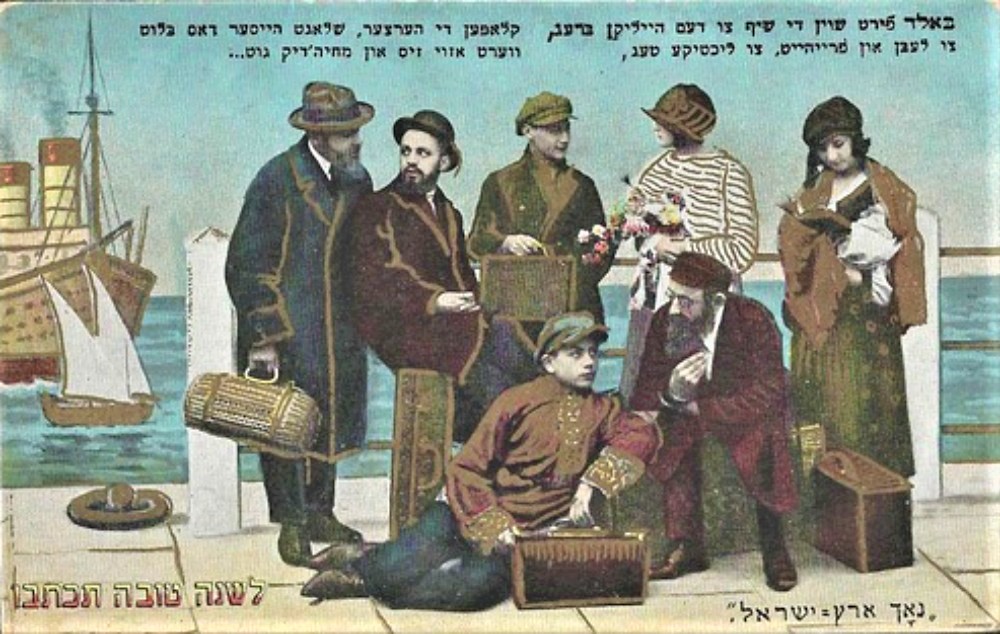

Each card features an illustration and a brief verse bracketed by the traditional Hebrew New Year greeting: “Le’Shana Tova T’katevu” – “May You Be Inscribed for a Good Year.”

The first card shows a group of Jewish men performing the “Tashlikh” or “Cast Away of Sins” service on Rosh Hashanah next to a body of water. The outfits, headgear and facial hair of each participant illustrates a different relationship to modernity, from the full beard and traditional garb on the left to the bowler hats and shaved or trimmed beards on the right.

The verse is religious in tone and meaning. It reads:

Vee shver ess zoll nisht zein de zind Vee groys zoll der kheit nisht zein Nehm alleh zei tzuneif atzind Un varf zei, Gott, in yam arein!

No matter how heavy the sin Or how great the transgression may be Gather them all in an instant And cast them, Lord, into the sea!

The second card portrays a dramatic contrast to the first. The two young women rowing the boat are distinctly modern. Their bobbed hair, fashionably colored clothing and the mere fact that they are involved in rowing without a man present suggests that they are somewhat rebellious against traditional norms.

The verse reads:

Es shvimt der shiffele shtillerheit Zvei khavertes derein A trug uns, shiffele, aheen Zum breg fun glick und freid.

The little ship swims silently Two girlfriends within thee Bring us, little ship, to there To the shore of luck and glee

The era of Yiddish postcards was also a dark and difficult one for the Jewish people. They were facing the rise of Nazi anti-semitism and genocide. In many cases their migrations were forced and not entirely voluntary. Nevertheless, reflecting the optimism of the holiday season, many New Year’s postcards indulge in lighthearted familial sentimentalism or romance.

In the next card, a pagan deity takes an incongruous turn and his target is pretty enough to be a Hollywood starlet.

Neu Yor Groisen…Liebe…Geld

Amor Tzielt…Dos Hertz’l kvelt

New Year Great…Love…Gold

Cupid aims…The little heart beams

The focus of optimism in many postcards is the attraction of new technologies – the automobile, radios, telephones, and airplanes, such as the next selection in our series:

Mir zogen eikh di b’shora on Es komt a sheyna tzeit Fun likht un shein fun glick un freid Di velt zi vert beneyet

We’re telling you the news A beautiful time is coming Of light and beauty of luck and joy The world is getting renewed.

Other cards dream wistfully of escape to a Jewish Nation State in the Land of Israel. In this New Year’s greeting a variegated group waits at an unidentified European port for a boat taking them to the Promised Land. The outfits of group members reflect the range of Jewish “types” of the period: Professional, religious, modern, and revolutionary.

“Nokh Eretz Israel”

“To the Land of Israel”

Bald fiert shoyn di shif tzu dem heyleken breg Tzu leben un freiheyt, tzu likhtige teig Klappen di hertzer, shlogt heyser dos blut Vert azoy ziess un mekha’yedik gut

Soon the ship will lead us to the holy shore To life and freedom, to enlightened days Our hearts are beating, our blood flows heating It’s becoming so sweet and pleasurably great

The despair in our final sample is so despairingly deep, it’s hard to believe that anyone would consider using this card as a greeting. Its theme of abandonment represents a common experience during the age of mass migration and Nazi-induced family disruption. However, it also is a metaphor for how Jewish people must have felt when rejected by their nations and neighbors.

Di Farlozeneh

Abandoned

Zitz ikh in shiffel doh eineh aleyn, Reist zikh in shtikker mein hartz fun geveyn… Himmel iz trauyrig, un shtum liegt der breg… Vasserel zog mir: Vu iz ehr avek?

Sitting here in my little ship all alone, My heart is ripped to pieces through tears… The sky weeps and silent lies the shore… Tell me little waters: Where has he gone?

The Yiddish language has held on precariously since many speakers of the language were murdered in the Holocaust. There has been a small revival of the language in recent years due to the popularity of Yiddish musicals from the turn of the 20th Century and Yiddish performances of “Fiddler on the Roof,” the nostalgic 1960s American musical based on the work of Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem.

The Polish-American writer in Yiddish, Isaac Bashevis Singer won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1978 for his lifetime of work. The verses of Yiddish postcards are much more prosaic and less refined than the masterworks of Yiddish literature but are still valuable for their charm and the insights they can deliver.

Fascinating article. Especially the people in modern dress who nevertheless spoke “the mother tongue”

When I was a kid, I learned a lot of Yiddish words by reading MAD magazine.

The greatest article on Yiddish that I have ever read.

Great history lesson…

I agree with Arthur Bennett below…this is the best article I have ever read about these postcards. Very appreciative!!