Bob Toal

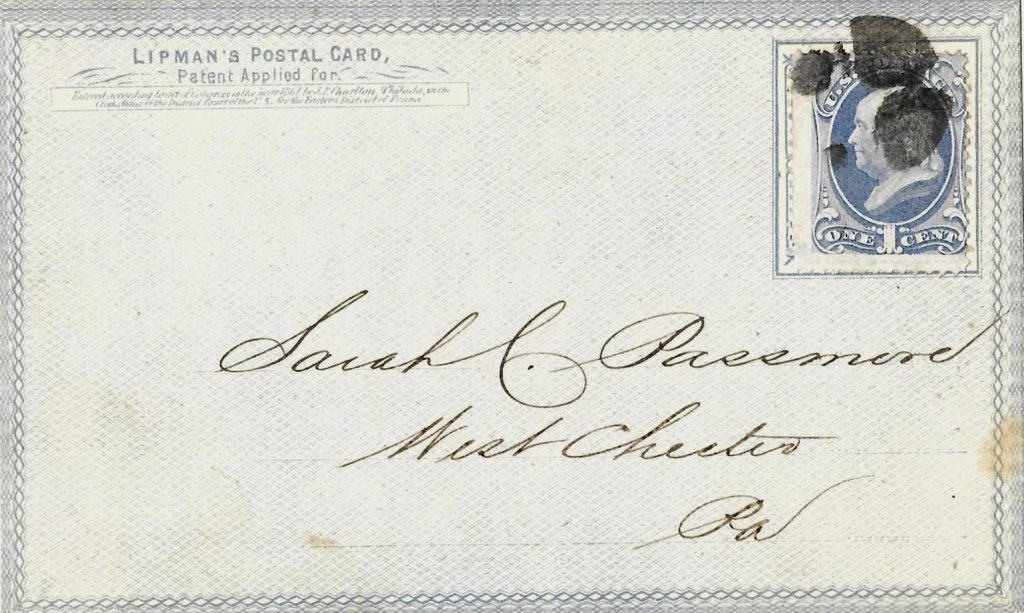

The granddaddy of the American Mailing Card is the Lipman Postal Card of 1872. It is the first private postcard successfully marketed to businesses for mailing advertisements. It also represents the first fully illustrated private postcard in America. As such, this card is historically significant. It is rare and commands a premium at auction.

As a point of clarification, postcards refer to privately printed cards that require a stamp for mailing. Postal cards (stamped cards since 1999) are issued by the Postal Service with an imprinted indicium prepaying postage. In the early days these terms were used interchangeably. Lipman’s card, though privately produced and requiring a stamp to mail was the first card to have the title Postal Card printed on it.

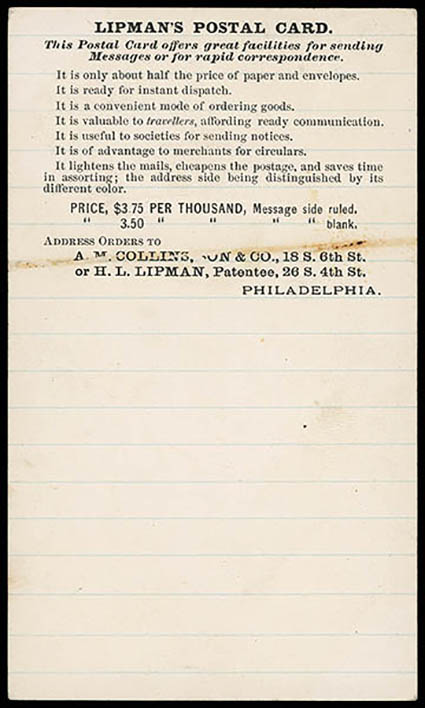

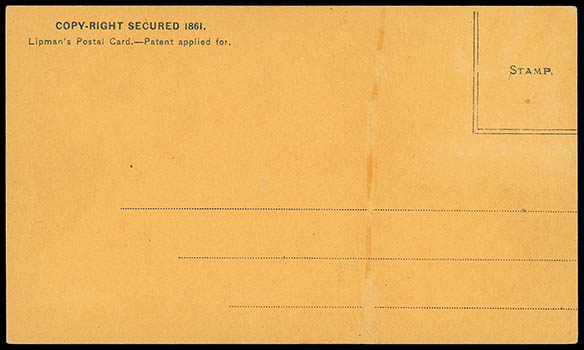

New researchpublished late 2019 totally updates our current understanding of this card and its origins. The Lipman card made its debut when the Post Office Department was soliciting essay design ideas and card samples for their first postal card. Lipman submitted his card as essay specimens but also advertised and sold his cards for commercial use. He advertised his first version in the Philadelphia Inquirer newspaper on March 19, 1872. It was a rather plain card and probably did not sell well. One of these cards with his own advertisement is below. In the upper left hand corner it has in fine print: “COPY-RIGHT SECURED 1861” and “Lipman’s Postal Card – Patent Applied For.”

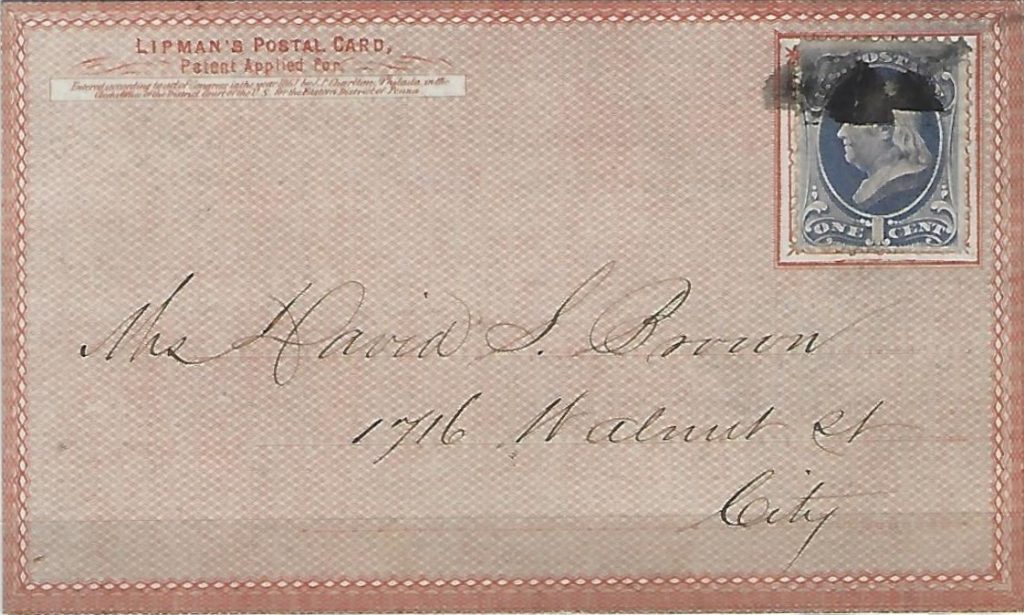

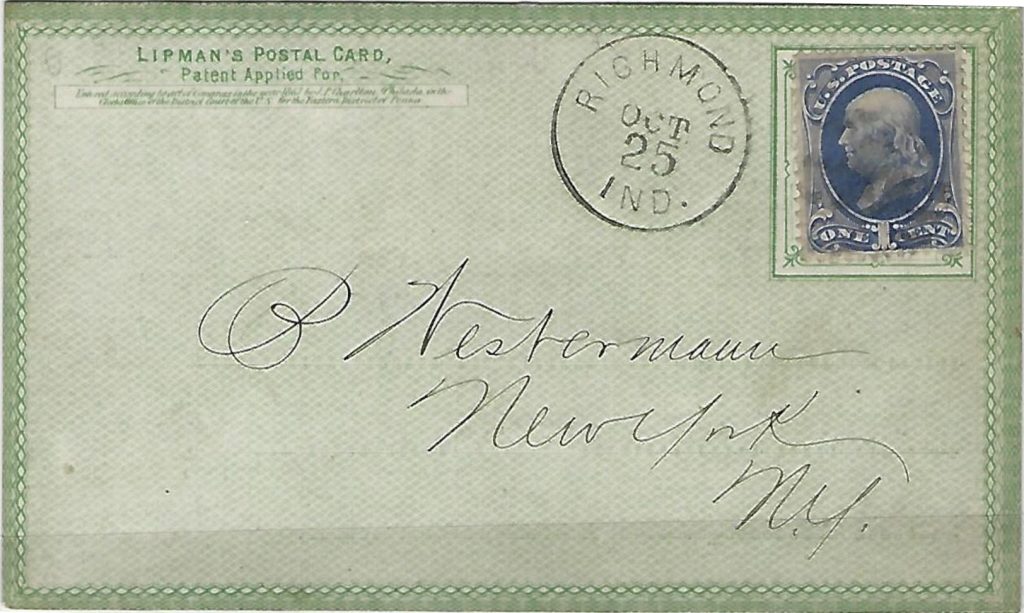

Lipman followed up with new designs in three colors: blue, red, and green. These were released May 28, 1872. He advertised them in the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Lipman cards in red, green and blue.

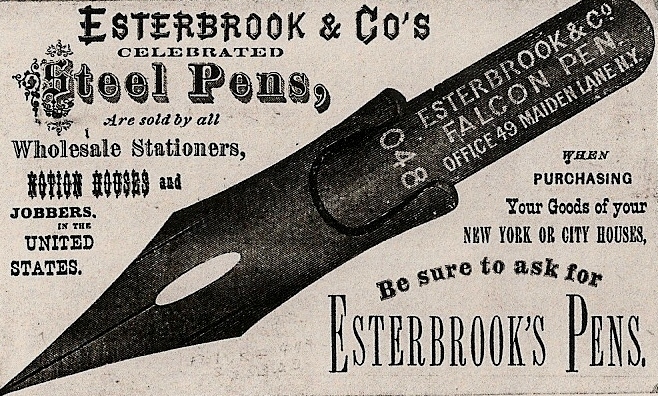

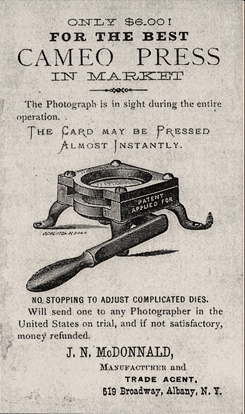

Each design was for printed matter use; printed ads mailed for one cent. These sold to a variety of businesses who printed ads or illustrations on the backs and mailed them. Several different examples have survived and a census of them has been published. The Type II card has printed in the upper left corner, “LIPMAN’S POSTAL CARD, Patent Applied For” and in a small boxed table, “Entered according to act of Congress in the year 1861 by J. P. Charlton, Philada. in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the U.S. for the Eastern District of Penna.”

Charlton’s 1861 copyright and “Lipman’s Postal Card – Patent Applied For” statement has always puzzled collectors. New research using original Library of Congress copyright records and Post Office documents conclusively show that Lipman or Charlton never got patents for postcards.

Charlton did get a copyright for a “Safeguard Envelope” in 1861 that had printed address lines, printed stamp box and return address box on the envelope. Two of these design elements were used by Lipman on his 1872 card – likely with Charlton’s permission.

Charlton once worked for Lipman, who was 16 years his senior, at the Lipman Stationer’s Warehouse. Lipman, Charlton, and another named Alfred Collins worked on Lipman’s postal card project.

The 1861 copyright notation and the “patent applied for” phrases were printed on Lipman’s cards to stifle competitors. In February 1873, Charlton sent a copyright violation warning letter to the Postmaster General when it became apparent the Post Office Department’s new postal card had printed address lines. The Postmaster General dismissed Charlton’s claim.

When the Post Office Department finally released their first postal card on May 12, 1873 Lipman’s cards faded away. His idea caught on later with others who began to print their own advertising cards on better stock. They often copied Lipman’s precedent by using the phrase, (Fill-in a name)’s Postal Card.

By the 1880s some of these private postcards were printed in sets by Goodsell and Crump and many doubled as trade cards. By the early 1890s private advertising cards later morphed into tourist cards sold at vacation sites. With the coming of the Columbian Exposition in 1893 the public could purchase high quality souvenir cards as keepsakes or to mail.

The postcard craze was about to begin.

The addresses on the differently colored cards provide several insights into the era — elaborate cursive writing, the simple use of “City” for a locally-delivered communication, and the lack of a house number for the second and third specimens.

Wonderful to be able to read about and see these incredible Lipman’s Postal Cards. Thanks for the documentation, and illustrations, and showing the color of the cards too. I love this stuff.