Nathaniel Dancer

Arches: A Series, Part IV

London

Back in 1605 a chap named Fawkes and a good many of his cronies started a to-do over some insignificant event that King James created with an edict that was much more of a deal then, than it ever would be today. It was all extremely unpleasant. And when the Catholic and Protestant things were whisked into the mix the results led to a period in English history known as the interregnum. It all lasted a bit more than a decade, but no one ever forgot it.

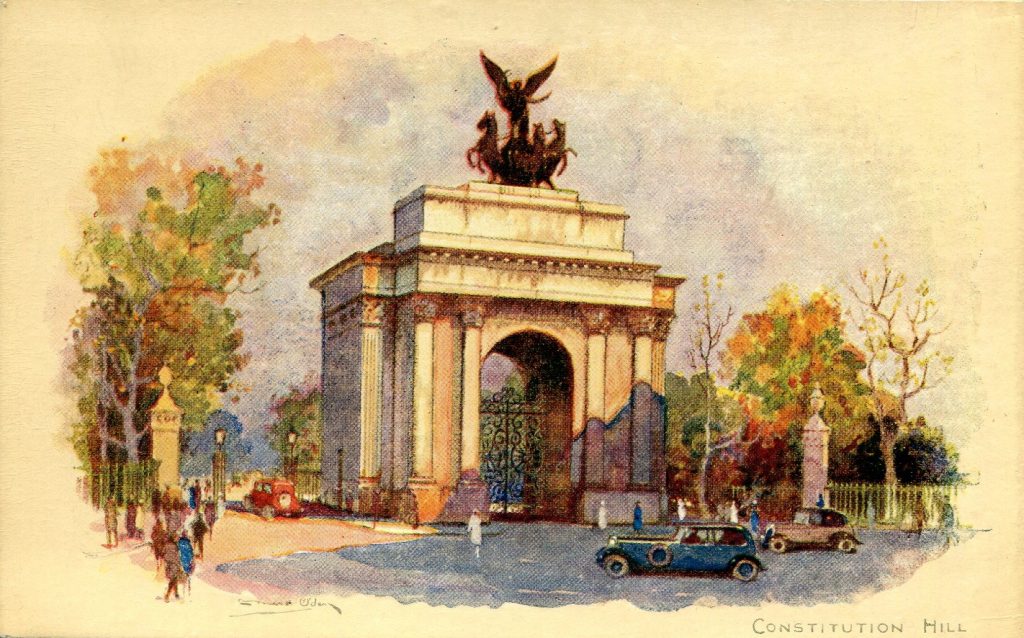

Just over 150 years later another chap, an Irishman, named Arthur Wellesley, did something else that the British have been agog over since. Wellesley and his cronies fought a battle over in Belgium against a fellow named Napoleon and his army. One would think such an event would be forgotten, but they built and arch and educated our children, now everyone is constantly reminded of the Battle of Waterloo.

I suppose it deserves mention that Arthur Wellesley, was usually called by his title; he was the Duke of Wellington.

The Wellington Arch was designed to be the main gateway to Buckingham Palace. It is based on similar designs, namely the Titus and Constantine arches in Rome. Such an entrance had never been seen before, but the English are by nature traditionalists who relish in honouring their heroes. Those who persisted (officially they were called the Commissioners of Woods and Forests) wanted to aggrandize the parks around the palace, and there was no better hero to honour than the Duke.

The committee found architects willing to attempt the project. Construction began in 1825 and it took two years to complete. When Victoria came, as a young girl, to the throne in 1837 it was not long before she grew into the epitome of tradition. She objected to having the arch in her front yard, but it stayed despite her objections.

There was another to-do in the 1840s when a statue of the Duke was created by a chap named Matthew Wyatt. The statue was intended for Green Park, but a suggestion came about, that it be mounted atop the arch. In the typical understatement used in the era, “it has a bit of charm, but it must be moved.”

In 1883 after fifty or more years of controversy the arch was moved. The Queen’s objections to it were finally heeded. Ostensibly to improve traffic flow, but it was often said that Victoria was now insisting that it be moved. Her reasoning included her fear that the portal was too narrow, her carriage could get stuck, and she would be trapped inside.

Being unable to argue with that kind of “royal reasoning,” a new location was selected and the arch was relocated to what many call the hub of royal London. For the rest of us, it is located at Hyde Park Corner.

The Wellington statue did not accompany the arch. A new sculpture was commissioned that is the largest bronze sculpture in Europe. It depicts the Angel of Peace descending on a four-headed-horse drawn chariot of war.

Today the Wellington Arch is one of the most visited landmarks in London. The arch is hollow inside, there are exhibits concerning the history of the arch and the Battle of Waterloo. It is not well known, but until 1992 the Wellington Arch was the home of the smallest police station in London.

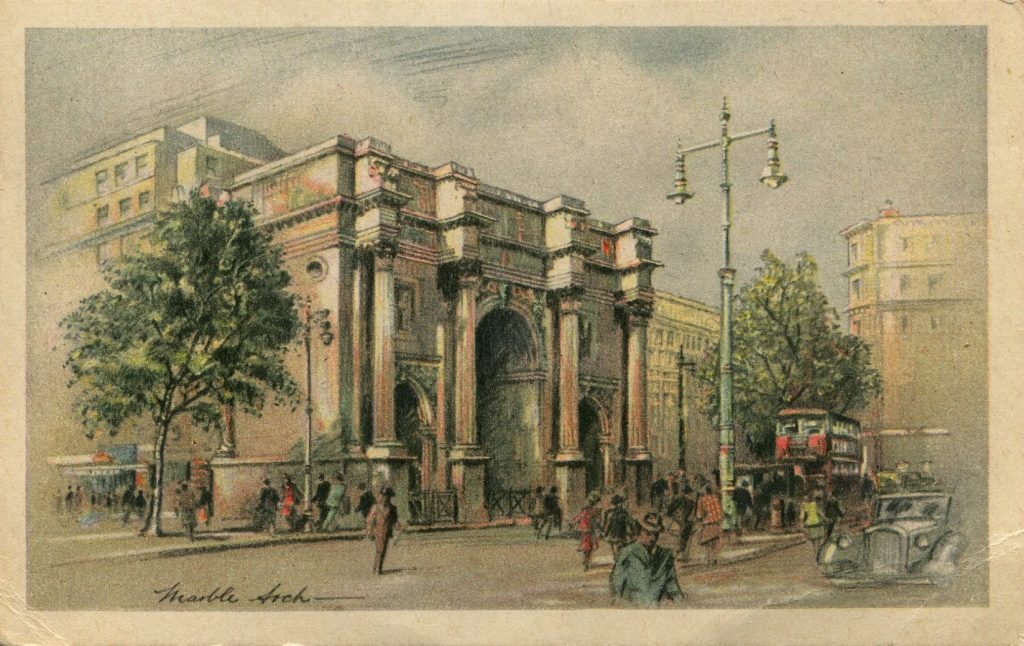

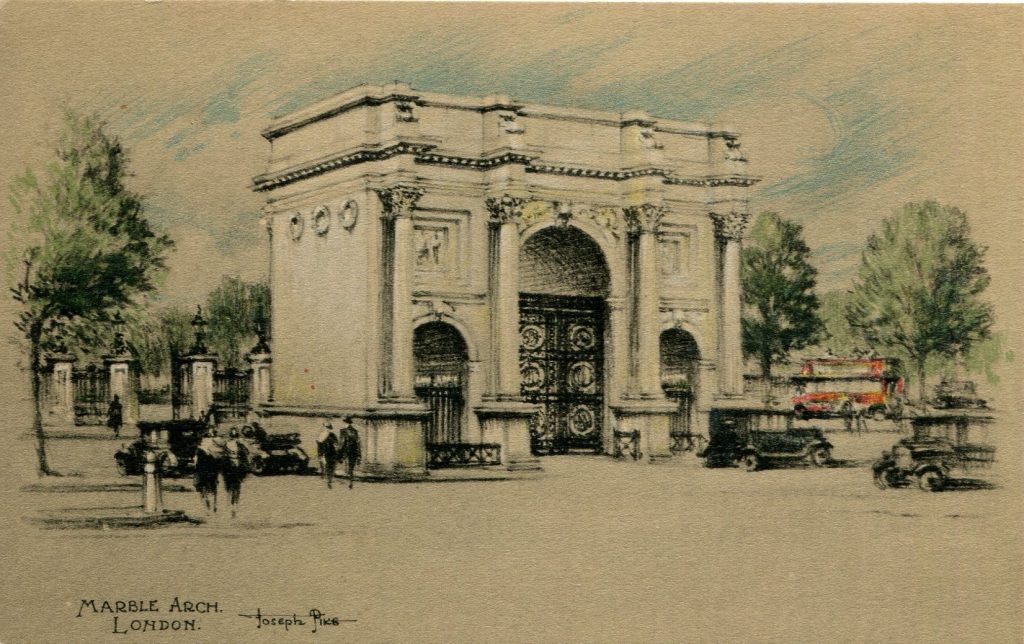

Marble Arch, like the Wellington Arch was modeled after similar structures in Rome. Wellington after Titus, Marble Arch after the arch dedicated to Constantine. And, like the Wellington, Marble was intended to be an entrance gate to Buckingham Palace.

Construction of Marble Arch began shortly after the completion of the Wellington. The dimensions are similar at 60 feet wide, 45 feet high, and 30 feet deep.

And, like the Wellington Arch, Queen Victoria had no affinity for the massive structure because it seemingly overwhelmed the palace.

The two arches have nearly identical histories; both were suffered by the royal family, both were moved from the front of Buckingham Palace to locations adjacent to Hyde Park, both were criticized for being too narrow to allow the queen’s coach to pass through, and both, in the later 20th century, had rooms used by the London Constabulary.

I have wandered the streets of metro-London for decades. I have studied the architecture of nearly every state, public, religious, health, and entertainment structure and have earned what you folks in America call an advanced degree in architecture. It is my considered judgement that London has most of the innovative and well adorned architecture in Europe. Of the three ages that I consider my specialty (Georgian, Victorian and Edwardian) men like John Nash, Sir John Soane, Sir John Taylor, and from the Edwardian era there is a fellow who worked his entire career to make the very best in architecture accessible to the common man. His name is well known to all first year architecture students. Just ask one of them who built the British Red Telephone Box, they will happily recite the name of Giles Gilbert Scott.

But before them all, Sir Christopher Wren stands among the tallest. Scholars from around the world know his name – even some of you Yanks know he was responsible for the Cathedral of Saint Paul and the Library at Cambridge.

Be sure to join me again, next time. I have a bonus surprise for you when we begin in Gibraltar and then travel along the western edge of the Mediterranean to Barcelona in sunny Spain. We will wander through the Plaça de Joan Fiveller to take a look at the first public fountain in Spain and then up the street to the Arco de Triunfo de Barcelona – one of the world’s largest brick structures.

Great article on the history of British architecture. I look forward to his “tour” of the coast of Spain.

Sir Christopher Wren

Said, “I am going to dine with some men.

If anyone calls

Say I am designing St. Paul’s.”

This poem, known as a clerihew, was written by Edmund Clerihew Bentley, who lent his middle name to the art form.