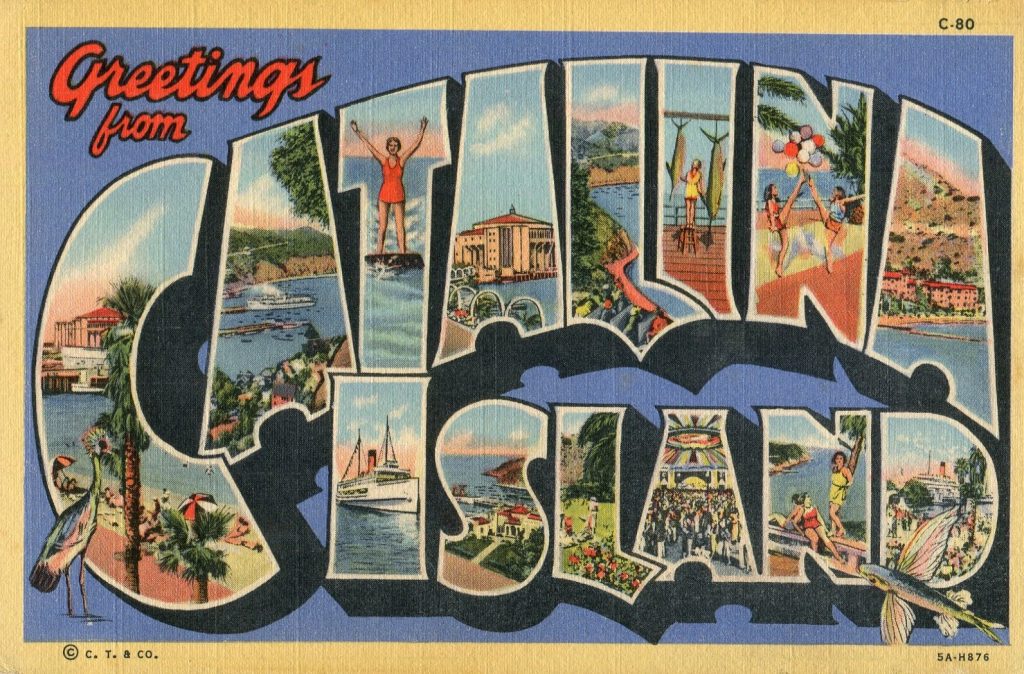

This 1935 Curt-Teich large-letter linen tells most of the story.

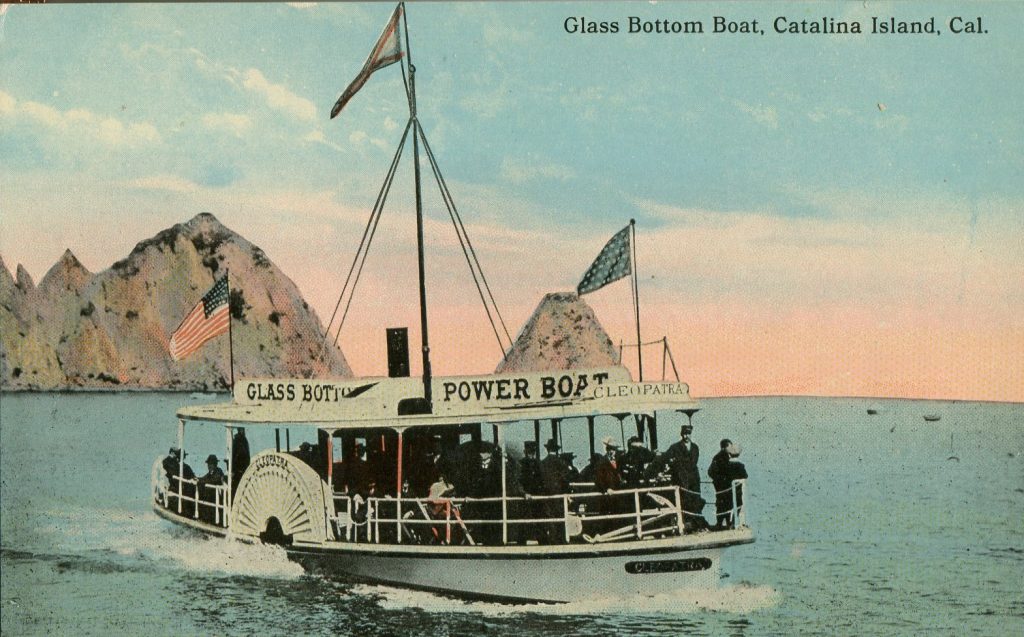

On Catalina Island there is plenty to amuse almost any taste in entertainment. There are sunny days on the beach, fishing, surfboarding, golf, concerts, hiking, dancing, or you can sit and watch the world go by.

Officially, Santa Catalina Island, is one of California’s eight Channel Islands. For administrative reasons, the archipelago is divided into the North Channel Islands group (Anacapa Island, population three; San Miguel Island, no permanent residents; Santa Cruz Island and Santa Rosa Island both with two residents each), and the South Channel Islands group (San Clemente Island, population 300; San Nicolas Island, 200; Santa Barbara Island, none; and Santa Catalina Island 4,096). The island populations, except for Santa Catalina, are based on U. S. Navy duty assignments.

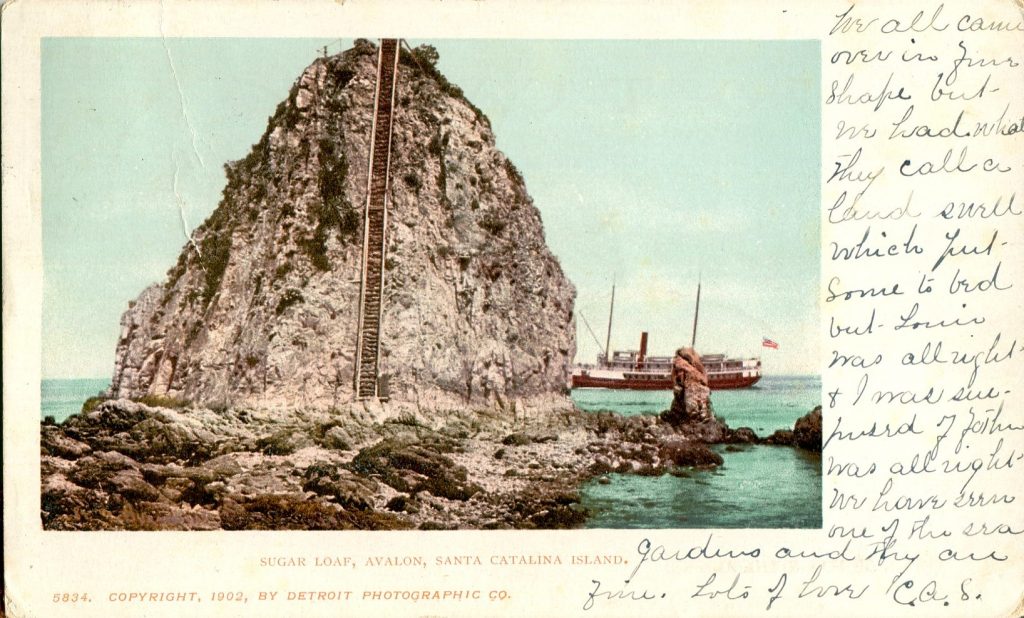

The large-letter card above does not tell the part of Catalina Island’s story that most fascinates historians. This part of the story begins on August 6, 1896. On that day it was announced that a new set of steps had been built which made it possible for visitors to Catalina Island to reach the top of the Sugar Loaf Rock.

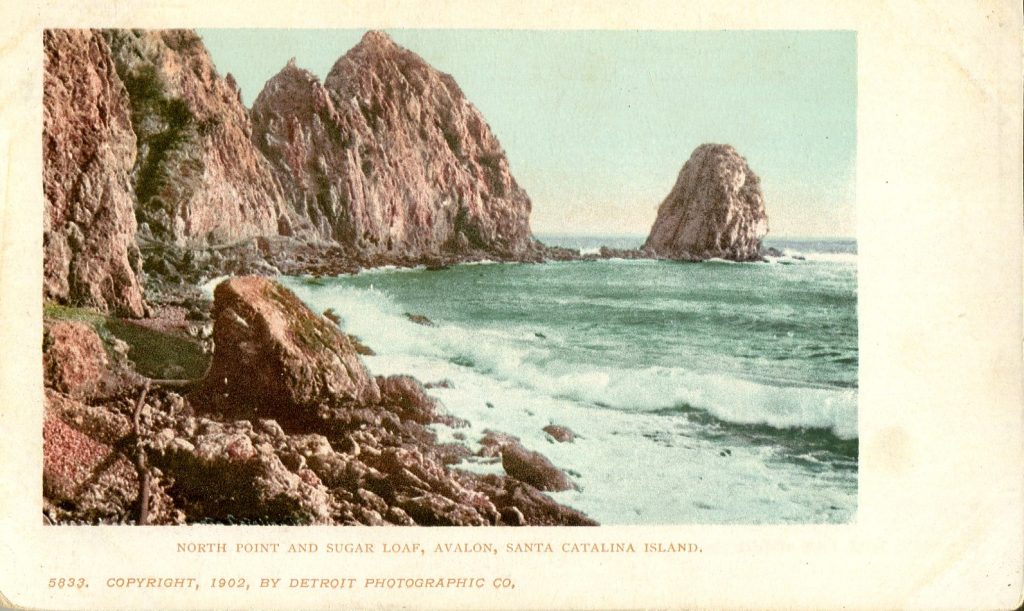

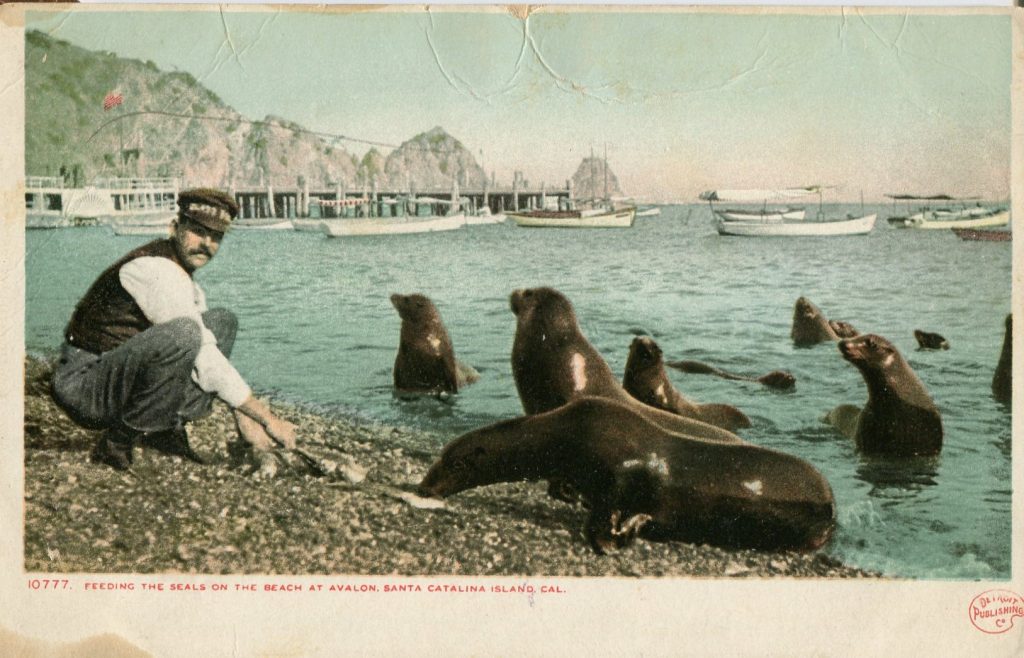

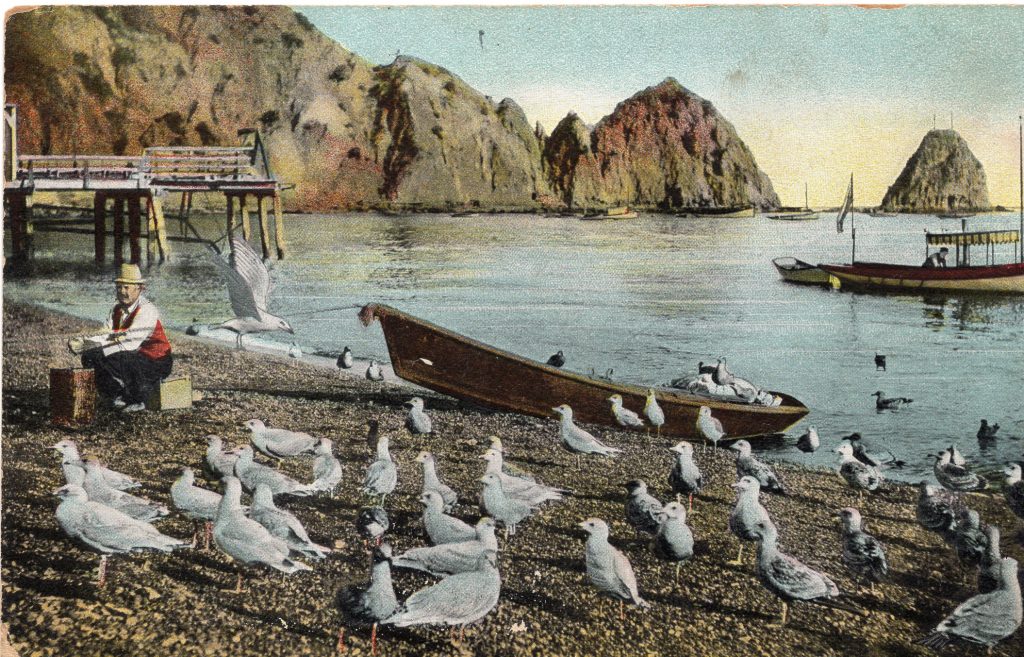

Whenever the first west coast explorer saw Sugar Loaf Rock is lost in time, but as it was, the volcanic monolith came to be Catalina Island’s most recognized landmark. At over fifty feet in height, it evolved to practical use in 1856 when William Enoch Greenwell built a survey station at the summit. He arrived early that year, just five years after California’s statehood, as a Chief Assistant in the U. S. Coast & Geodetic Survey for the Channel Islands. The station accommodated the work he continued in California until his death on August 27, 1886, at age 62.

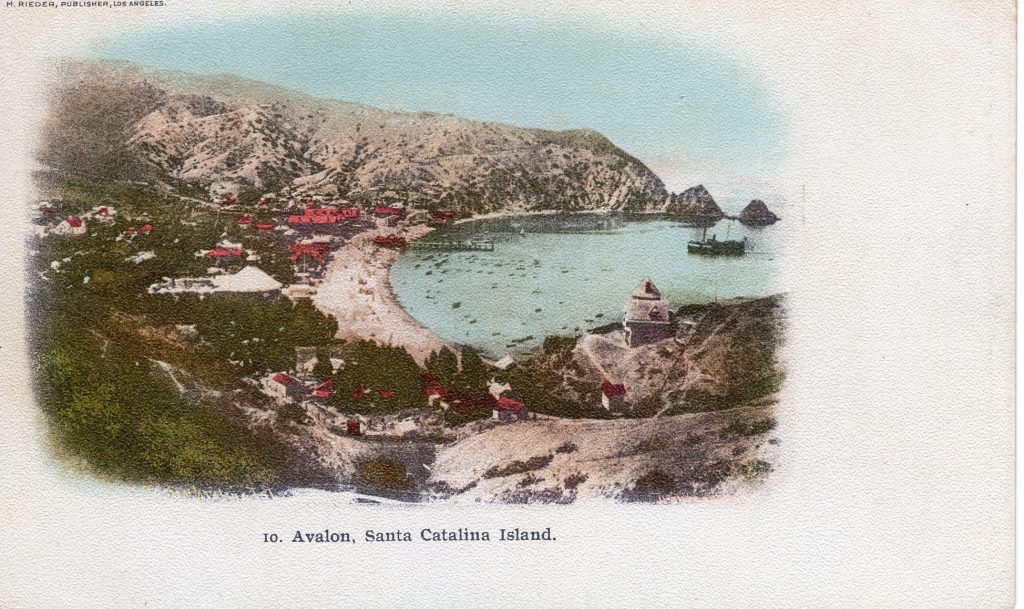

In true Paul Harvey style, here is the rest of the story, but first, a brief look-back. From 1864 to the early 1890s, Catalina Island was wholly owned by the richest man in California, James Lick. Lick’s attempts to develop tourist and vacation opportunities on the island failed. Thinking it a lost cause, Lick sold the island to brothers named Bannon who built hunting lodges and conducted stage-coach tours. The Bannons had better luck than Lick but then in 1915 came a fire that burned more than half the city of Avalon. The brothers lost again when they attempted to reclaim their investment. The lack of proper insurance and the lack of guests in their new hotels forced them to sell in 1919. All Bannon interests went to William Wrigley, Jr., the Chicago chewing gum king.

Wrigley bought every share of the Santa Catalina Island Company available until he gained control. In the following years, Wrigley exhibited no shame in the amount of money he spent on his “vision to create a playground for the world” on Catalina Island.

Wrigley’s vision included new residential housing with the necessary infrastructure that included a freshwater reservoir, new hotels, parks, and business opportunities. He also envisioned the island as the spring training site for his Chicago Cubs baseball team. The team continued to use the island for training for the next thirty years.

Almost immediately Sugar Loaf Rock became a target of Wrigley’s loathing. He wanted to build a casino at that location in Avalon Harbor. Under Wrigley’s direction his company manager, David M. Renton instructed crews of demolition specialists to dynamite the rock and clear the ground for what would become the Sugar Loaf Casino.

That was what Wrigley wanted but it was not what he got. The casino was built but the rock remained – at least for another decade. The casino was not a gambling hall, but a dance pavilion and motion picture theater – the first ever to be designed specifically for “talkies.”

Money and the accumulation of wealth never seem to be enough for some men. In 1928, Wrigley by way of his own self-determination decided that his casino was not large enough. He had the first casino razed and a larger one built – the one that still stands on Sugar Loaf Point serving the same purpose as the first – a dance pavilion (on the second floor with space for 2,000 couples) and motion picture theater (on the first floor with seating capacity of 2,500).

This time he got what he wanted. The walls of the new “Grand” Casino overshadowed the rock and in March 1929 Sugar Loaf Rock was dynamited into oblivion because it ostensibly blocked the view of the new building from boats entering the harbor.

An artistic version of the demolition, but a totally inaccurate image.

Remember the park mentioned above? When the original casino was demolished the interior frame of the structure was removed to an inland area where Wrigley instructed that it be re-assembled into the world’s largest flight-cage (the cage was 90 feet tall and 115 feet in diameter). Wrigley and his wife Ada were both avid birdwatchers. The Catalina Bird Park closed in 1966.

Wrigley died in 1932 but Catalina Island remained unchanged. Philip K. Wrigley, known to most everyone as P.K., who was far less boisterous than his father, took charge of all Wrigley interests until the early 1940s when the island was used exclusively for military training. All tourism was forbidden.

Philip K. Wrigley died in 1977, but to this day, descendants of William Wrigley, Jr. still own the Catalina Island Company and carry on his vision.

Too bad that beautiful and legendary Sugar Loaf Rock can be seen only on postcards.*

* Special thanks to Shav LaVigne for the use of his postcards used to illustrate this article.

The Lick observatory, which at one time featured the world’s largest and most powerful telescope, is among James Lick’s legacies.

Wow! Even more enjoyable than the Great White Fleet. What a delight this site is!

“Its Always Something” that Gilda Radner used to say. Interesting article.