George Miller

America’s Fraternal Brotherhood

My father was a joiner: he was a Moose, an Elk, a Mason, a Shriner, and an American Legionnaire. It’s true that we lived in a small town and there wasn’t much else to do, but his interest in such organizations was much more complicated than small-town boredom. Like all of us he enjoyed the feeling of being a part of something; he enjoyed the rituals of the Masons; he saw a security in his fraternal memberships.

My father was a joiner: he was a Moose, an Elk, a Mason, a Shriner, and an American Legionnaire. It’s true that we lived in a small town and there wasn’t much else to do, but his interest in such organizations was much more complicated than small-town boredom. Like all of us he enjoyed the feeling of being a part of something; he enjoyed the rituals of the Masons; he saw a security in his fraternal memberships.

Patriotic Order of Sons of America, in Tower City, Pennsylvania, about 1907.

Mutual assistance The primary purpose of a benevolent society is to protect its members and their dependents and to engage in charitable work among those in need or distress. Two of the most important of these societies are the Knights of Pythias, founded in 1864, and the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, founded in 1866. The Knights were first organized in Washington, D.C., around the story of the friendship between two young men, Damon and Pythias. Damon, under a death sentence, asked to be allowed to say good-bye to his family. Pythias confident of is friend’s return, agreed to act as hostage. Damon, of course, returned and the bond of trust and friendship served as an example to others. The Elks, on the other hand, were originally a group of actors and writers known as the Jolly Corks. One day some members visited Barnum’s Museum in search of a suitable name. Bears and beavers were ruled out before the group decided upon the elk. A number of other benevolent societies also chose animal names including the Loyal Order of Moose (1888), the Fraternal Order of Eagles (1898), the Order of Owls (1904), and the Fraternal Order of Orioles (1910).

Catholic Ladies Union Fraternal Insurance Society

Insurance societies carried the idea of protection a bit farther. Generally they worked through a system of mutual assessment. Whenever a member died, the remaining member was assessed a certain amount of money which then became a cash payment to the survivors. The first such organization in the United States was the Ancient Order of United Workmen (1868). Others included the Independent Order of Foresters (1874), the Royal Arcanum (1877), the Maccabees (1883), and the Modern Woodmen of America (1883). Many of the patriotic societies were formed as conservative reactions to the huge influx of Roman Catholic immigrants during the late 1800s and early 1900s. One group which does appear on postcards is the Patriotic Order of Sons of America (1847) which supported an “America for Americans” and opposed unrestricted immigration. Most fraternal organizations in this country have some type of religious element in either their organization or their ceremonies. Some are directly affiliated with religious faiths. The most obvious example is the Knights of Columbus whose members must belong to the Roman Catholic Church.

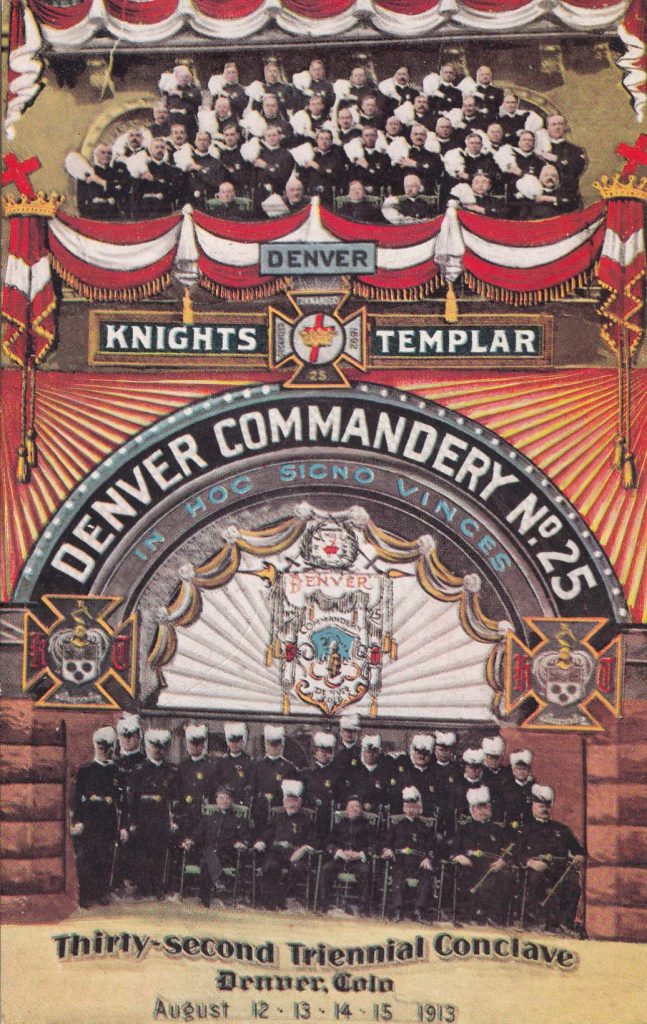

Souvenir of the 32nd Triennial Conclave, Knights Templar, a “uniform rank” of the Masons

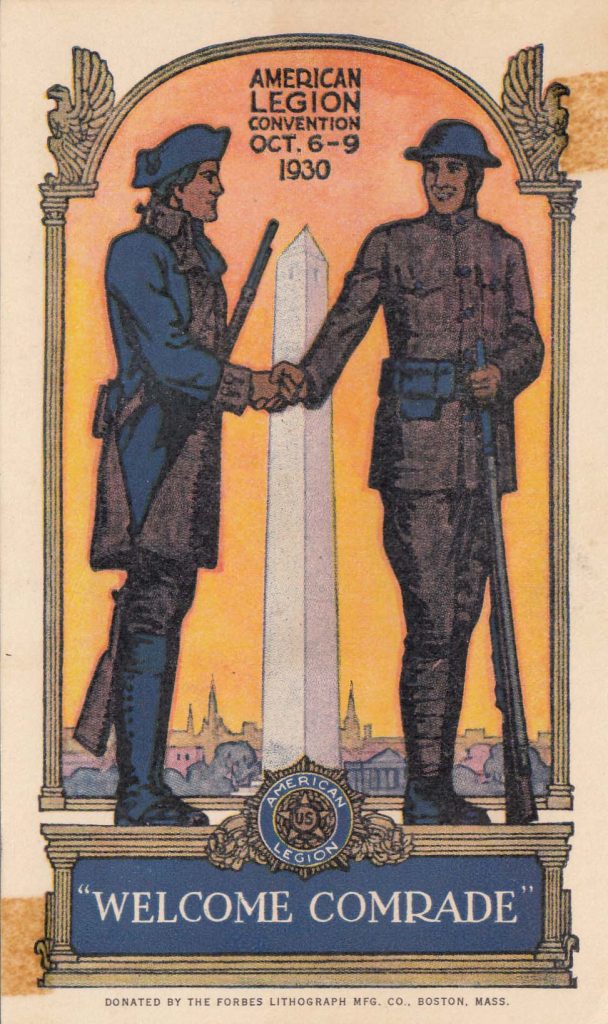

Souvenir of the 12th National Convention of the American Legion, Boston, 1930.

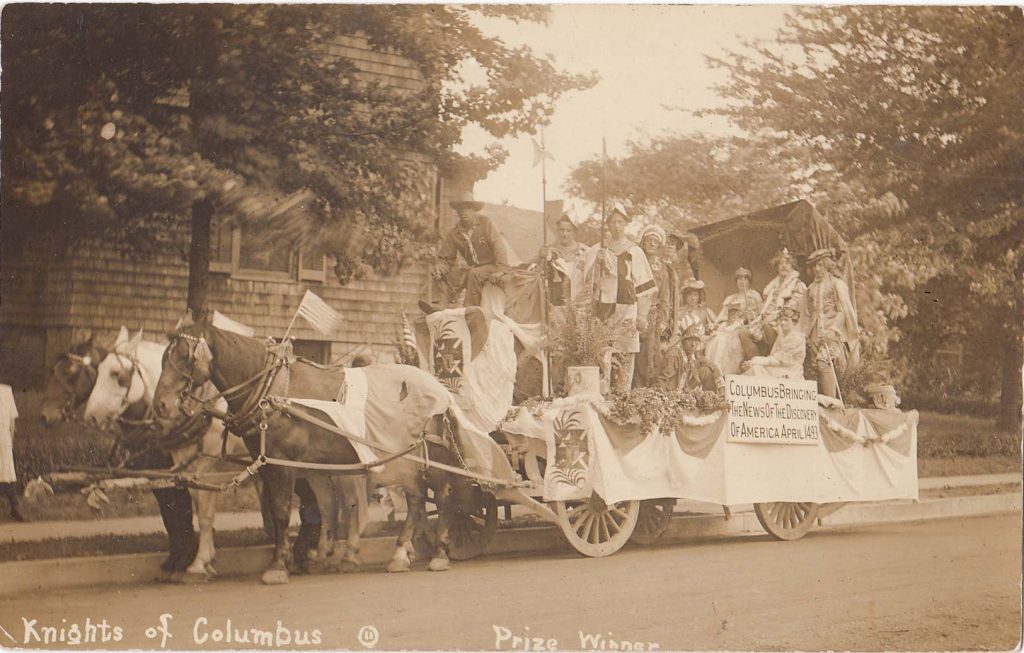

Two of the larger fraternal organizations in this country began in England and were then introduced later here. The first grand Masonic lodge was formed in London in 1717 and by 1730 Freemasonry had come to the colonies. The Independent Order of Odd Fellows began in 1745, but it wasn’t established here until 1819. Other groups were native-born, such as the Improved Order of Red Men. Auxiliary groups for wives and children The fraternal organization is still essentially an adult male fortress, sort of a democratic equivalent to a gentleman’s club. Women are generally organized in satellites or auxiliaries around the fraternity. There are the Order of Eastern Star (Masons), the Degree of Pocahontas (Red Men), the Daughters of the Rebekah (Odd Fellows), and the Pythian Sisters (Knights of Pythias) just to name a few. Most fraternities also have junior auxiliaries for children: the Red Men have the Degree of Hiawatha (boys) and the Degree of Anona (girls); the Knights of Pythias, the Pythians Princes of Syracuse (boys) and the Sunshine Girls; the Masons, the Order of De Molay, the Order of Builders, and the Order of Chivalry (boys) and the Order of the Rainbow and Job’s Daughters (girls). For those with a fondness for ritual, pageantry, elaborate uniforms, and discipline, many fraternal organizations have subordinate or subsidiary orders modeled on medieval knighthood or some other military organizational pattern. These “uniform ranks” include such groups as the Knights Templar of the Masons and the Patriarchs Militant of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows. Fraternal membership declines in 1930s Fraternal memberships in the United States peaked in the 1920s. The Depression and the economic disaster it occasioned contributed to the decline, but other factors figured just as significantly. New leisure-time activities such as movies, radio, daily newspapers, and the automobile, took time away from “lodge” activities. The elaborate rituals, once so popular a part of the fraternal experience, seemed increasingly silly. Noted sociologists Robert and Helen Lynd in Middletown (1929), a classic study of life in a small midwestern city, wrote: “The great days of lodges as important leisure-time institutions in Middletown have vanished. Businessmen are ‘too busy’ to find the time for lodge meetings that they did formerly; the man who goes weekly to Rotary will confess that he gets around to the Masons ‘only two or three times a year.’ Working men admit, ‘The lodge is a thing of the past to what it was eight or ten years ago. The movies and autos have killed it.’ ‘He belongs to a lodge but never goes,’ said more than one of the working-class wives interviewed. The shift in leisure-time activities was just one part of the change. Similarly, for example, the need for “protective” functions has also decreased. Social Security, pension and disability plans, IRA’s, and a host of government programs have greatly reduced our need for fraternal protection. Homes for dependent members—orphans, widows, the elderly—once an important benefit of membership have nearly disappeared, although many groups still help support members and their dependents in both public and private institutions. Fraternal groups on Postcards Fraternal organizations are a distinctive and important part of our national cultural life. Because the popularity of such societies coincided with the popularity of the postcard, the collector has a wealth of inexpensive cards from which to choose. Fraternal cards, regardless of the organization represented, generally fall into three large groupings. First are views of homes, hospitals, and lodge buildings. Even as late as 1940 there were an estimated 190 to 200 fraternal homes and hospitals in the United States. Probably many hundreds of local lodge buildings also appear on postcards. Since most of these structures have either been destroyed or are now used for some other purpose, such a collection documents a lost era. The second grouping are cards of fraternal parades or of national or state conventions. Any organization might be found parading on a real photo postcard, but commercial issues connected with conventions were generally limited to the very large organizations like the Benevolent and Protective Order of the Elks whose annual conventions, such as those in Philadelphia (1907), Dallas (1908), Los Angeles (1909), Detroit (1910), Atlantic City (1911), and Portland (1912), are extensively represented on cards.

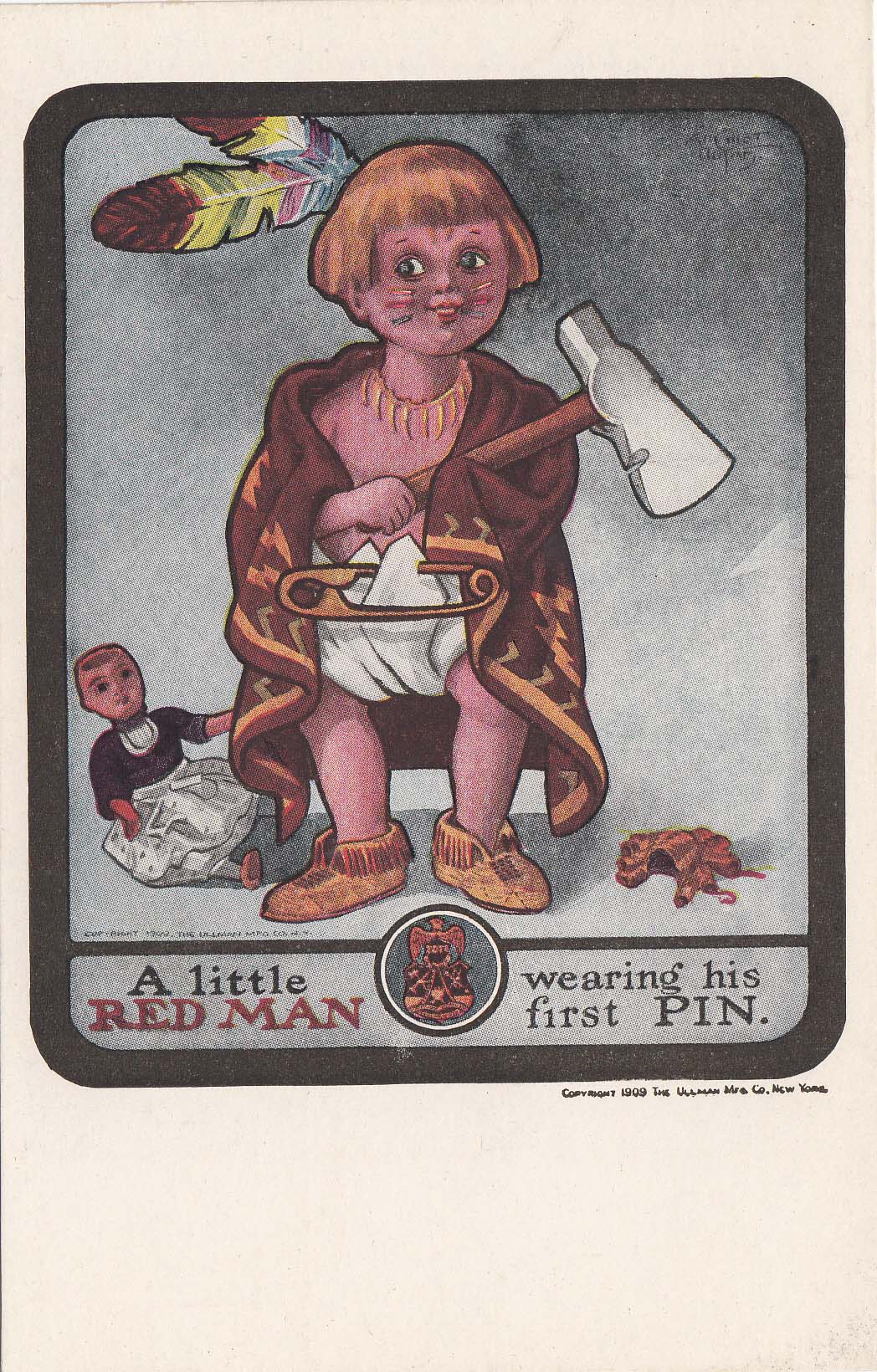

Knights of Columbus float in a New Jersey parade

The third grouping is comic postcards. Generally they make fun of the rituals involved (for example, “riding the goat”) or they see a comic context for a particular phrase (a member’s “first pin” — his diaper pin — or “midnight at the Elk’s home”— with two women waiting at home with rolling pins). Ullman Manufacturing Company was one of the major producers of fraternal comics including an especially attractive set signed by artist August William Hutaf (series 134). Artists Lou Mayer and Bernhardt Wall also did sets of fraternal comics. Many fraternal collectors specialize in the organizations to which they belong. Masonic cards are probably the most popular. But many of the earlier fraternal organizations, some of which are now either small or defunct, seem particularly attractive. Why not focus on one of those societies such as Fraternal Order of Eagles, the Knights of the Golden Eagle, the Knights of Pythias, or the Royal Arcanum? For Further Reading:- Fraternal Organizations, by Alvin Schmidt. Westport, CT, Greenwood Press, 1980. A good source for specific organizations.

- Encyclopedia of Associations. Consult this for membership information and addresses.

Growing up in New York City in the 1950s, I did not see these. What was around were the ethnic parades, Irish, Italian, and Puerto Rican. Later, living in a much smaller town I became aware of Elks, Moose, Columbus Lodge, and Columbian (F&AM). This article explains so much about why they existed and what their past had been.

Great article!

I had often heard of my grandparents involvement in Faternal societies. It was something I never really understood. This article really gave me a much better grasp on their lives. That is something I will treasure forever. Hope to come across some of these type cards sometime. I also saw the Pythius info. Is that What Pythian castles were for? We had one in Weiser and its a pretty iconic structure. I even thought about purchasing it once, ghosts and all. hahaha.

Thank you for sharing.

I live in Lafayette, Indiana, where a Pythian Home for orphans once stood. The city also hosts the J. H. Rathbone Museum of Fraternal History, which focuses on the Knights of Pythias.

And then of course there was that widespread organization, the KKK. Although some membership restrictions applied.

Laurel and Hardy did a funny spoof of fraternal societies in the thirties. By then they were on the decline.