Alan Upton

Watches for Sale

The standardization of time within sharply drawn time zones was the purview of the American and Canadian railroad companies. It took years and thousands of people to institute standard times and on November 18, 1883, the “switch” from local to standard times was thrown.

No one knows if it was instant but that day, standard times were set in North America’s eight time zones:

- Newfoundland/Labrador (time is set at one and a half-hour ahead of Atlantic Time.

- Atlantic Standard is minus 4 hours from Coordinated Universal Time (UTC)

- Eastern Standard is minus 5 hours, UTC

- Central Standard is minus 6 hours, UTC

- Mountain Standard is minus 7 hours, UTC

- Pacific Standard is minus 8 hours, UTC

- Alaska Standard is minus 9 hours, UTC

- Hawaii Standard is minus 10 hours, UTC.

Prior to standard timing most places, villages, hamlets, towns, and cities chose to rely on local-solar time. When the sun was highest in the sky, it was noon, and the best-known clock around, the one in the jewelry store window or in the church steeple was set accordingly.

[Suggested Reading: “The International Meridian Conference,” Postcard History, September 15, 2019]

One unintended consequence of standard time settings was that it created a need (or at least a desire) for most people to own watches. Imagine yourself as a person who wanted to own a watch to keep track of your hours and minutes in the 1890s. You never owned a watch before and you’re interested but don’t want to spend a great sum of money. Where do you go to buy your watch?

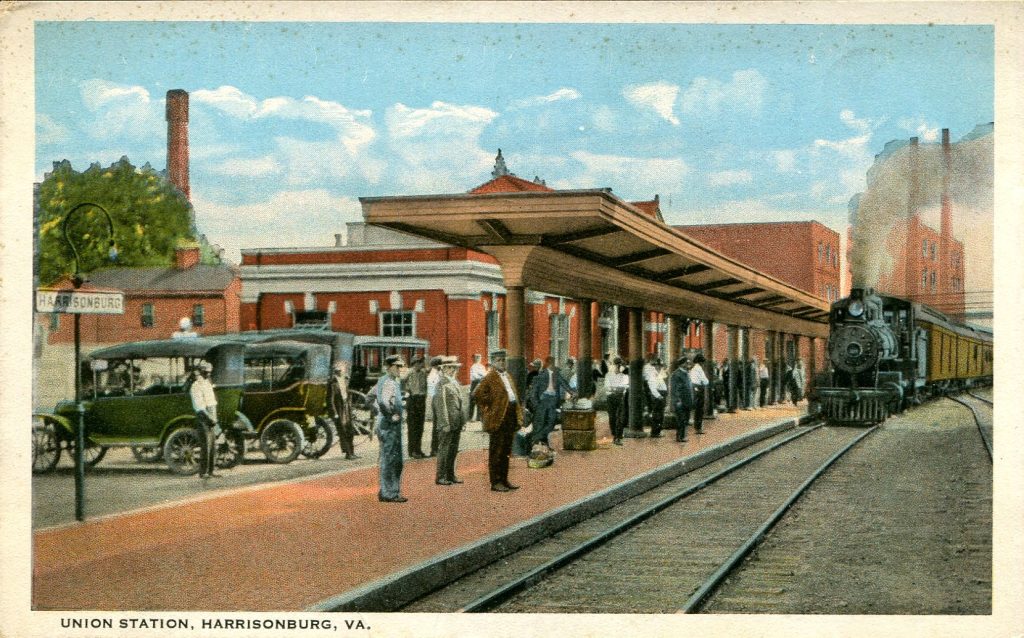

You could go to a store, a local jewelry store perhaps, or a watchmaker’s shop. Sure, you could do that, but remember your budget is tight. If you wanted one that was cheaper and a bit better than most of the store watches, you went to the train station!

Does this sound peculiar? Maybe! Does it make sense? Probably not. But, in over five-hundred train stations across the United States, that was where the best watches were found.

It had nothing to do with standard time or the railroads. The railroads weren’t selling the watches, it was the telegraphers. Most of the time the telegraph operator was located in the railroad station because the telegraph lines followed the railroad tracks from town to town. It was usually the shortest distance and the right-of-way had already been secured for the railroad.

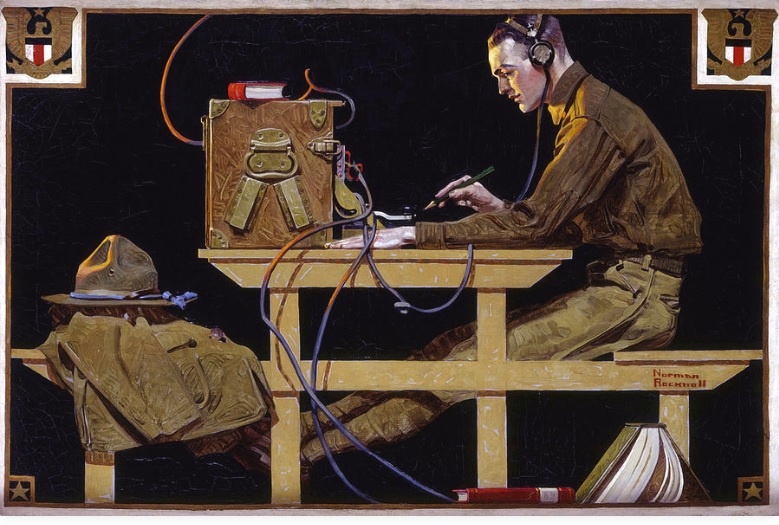

The Telegrapher by Norman Rockwell

Most station agents were also skilled telegraph operators and telegraph was their primary means of communication with the railroad offices and each other. From the telegraph they could learn when trains left the previous station and when they were due to arrive, often bringing necessities of life: newspapers, foodstuffs, building supplies, home products, and passengers. And it was the telegraph operator who had the watches for sale. It is fact that more watches were sold by telegraphers than in stores for a period between the mid-1880s to the late-1890s.

Detail from a 1961 chrome advertising

Biltmore “Dollar” Watches.

The responsible individual was a telegrapher name “Richard.”

Richard was on duty at the train station in North Redwood, Minnesota, the day a load of watches arrived from back-east. It was a huge crate, and it was moved into the dispatcher’s office to await a claimant. No one came.

Perhaps weeks later, Richard sent a telegram to the manufacturer and asked them what to do with the watches. The manufacturer didn’t want to pay the freight back, so they replied with an offer to Richard to see if he could sell them. This offer would change his life – forever.

Sell them he did! He sent wires to every agent in the system asking them if they wanted a cheap, but good pocket watch that they could sell for their own profit. The entire case was committed to sales far and near in less than two days and at a handsome profit.

He ordered more watches from the company and encouraged the telegraph operators to set up display cases in their stations offering high-quality watches for a cheap price to travelers.

It worked and it didn’t take long for the word to spread. Orders arrived from station agents outside of the system Richard was employed by and those orders were given as much attention as any other. Before long, people other than travelers came to the train station to buy watches.

Richard was so busy that he had to hire a sales staff and a professional watchmaker to assist with the orders. The watchmaker, whose name was Alvah, became Richard’s partner in 1891.

The partnership of Richard Sears and Alvah Roebuck was legendary. After moving their business to Chicago, their enterprise expanded and became an international business with few rivals.

Wonderful story. My dad worked for Sears for many years.

What an interesting insight. I have always wondered where the name “Sears & Roebuck” came from. Another example of learning about history through postcards. Thank you.

A timely story extolling entrepreneurs at their most creative and impactful. They changed retail in America the way Amazon has today. Ultimate lemonade story.

I can always count on this magazine to lift my spirits! What a cool story!

So we’ll written! Fascinating. Thank you.

Great story. Brought to mind one of our favorite photos- a sign posted before the market stalls after the exit of the ruins at Ephesus Turkey that read “Genuine Fake Watches”

Great story, well told. I had not known that that was how Sears and Roebuck had their start. A small correction: Newfoundland time is only 1/2 hour ahead of Atlantic time, rather than 1 1/2 hours ahead. I expect you meant to write “one half hour” as opposed to “one and a half hour”.

I figured out who Richard was as soon as his name was given, and the mention of “Alvah” let me know I was on the right track. Fascinating bit of history!