George Miller

The Bonus Army

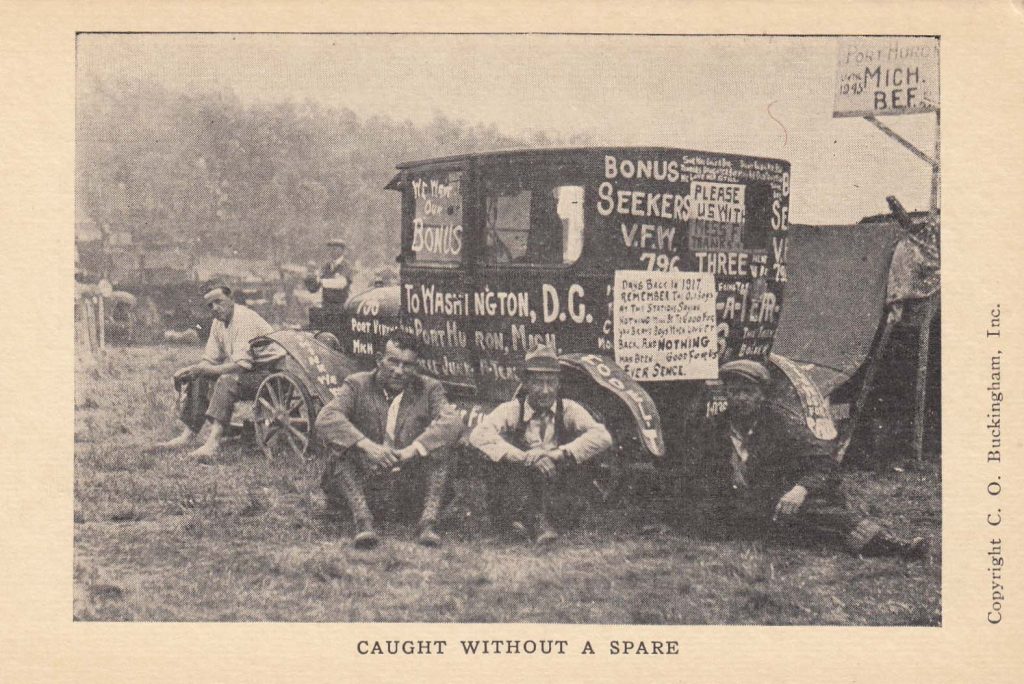

Bonus Seekers from VFW Post 796 in Port Huron, Michigan, at Camp Marks

At 4:30 PM on July 28, 1932, General Douglas MacArthur led a small army composed of some 200 cavalry, 300 infantry, and five tanks down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C. Its mission: to clear Washington of an estimated 8000 or so World War I veterans, the remnants of a much larger group (perhaps as many as 25,000) who had begun assembling in the capital in May. This Bonus Expeditionary Force, as it was called, had come from all over the country to demand that Congress immediately pay their service “bonus” not due until 1945. Congress refused and President Hoover ordered out the Army.

Within an hour the troops with drawn sabers and some 1500 tear gas bombs had cleared the downtown areas. After pausing for dinner, the Army moved across the bridge to Anacostia Flats, the site of the shantytown Camp Marks, which had served as home for the majority of the BEFers and their families. By midnight the camp had been burned and the destitute bonus marchers driven out of the city and left to fend for themselves. Nearly 6000 regrouped in the next few days at the Ideal Amusement Park in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, but with little food or water and no prospects for improved conditions, this last group dispersed by August 6

th.

The whole incident, from its spontaneous beginnings to its violent end, was a curious moment in American history. The country was in the grip of the Great Depression. One-fourth of the people belonged to families which had no regular income; over 13 million Americans were unemployed. Those fortunate enough to still have jobs generally earned substantially less than they had in the 1920s. In an age before federal relief programs, the little public welfare available on the state or local level was totally inadequate. The frustrations of the veterans were understandable, the reaction of the federal government to their sit-in much less so. In fact, as a recent historian observed: “Perhaps no other incident better symbolizes the utter inability of Herbert Hoover’s administration to understand and to cope with the unprecedented problems of the Great Depression.”

Veterans’ benefits have probably been around since the beginnings of organized warfare. In our century, the rationale is two-fold: first, to reward those who have risked life and limb in defending our country, and second, to narrow the gap between the earnings of civilians and those of soldiers during the war years (assuming always that civilian workers made more than servicemen). American soldiers in the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, and the Mexican War all benefited from a system of bonuses—generally grants of land. Such benefits posed no real financial burden on the government. The number of men eligible was small and land was plentiful. After the Civil War, however, the cost of veterans’ benefits skyrocketed. Increased pensions were a great plank in a party’s platform and successive Congresses enacted more and more generous legislation. By 1893, veterans’ benefits amounted to 43¢ of every $1.00 spent by the federal government.

With the outbreak of World War I, the government was concerned about holding down benefit costs. As a result, Treasury Secretary McAdoo drafted a scheme whereby wives of servicemen received $15 a month, $10 for a first child, $7.50 for a second, and $5 for each additional child up to a monthly maximum of $50. This was financed by withholding half of each enlisted man’s pay (later changed to a maximum of $15 a month). The government made up any difference between the two amounts. Similarly a schedule of payments for death or disablement was established and life insurance was subsidized so that servicemen could purchase insurance at roughly the same rate that civilians could. Setting aside the cost of the insurance programs, by the time the allotments and allowances ended in July 1921, the government had actually collected more from servicemen than it had paid out.

Despite such prudent planning, the war was no sooner over than Congress began to consider other bonus schemes. Bonus legislation was not enacted until 1924, almost six years after the armistice, and then only after both houses overrode President Coolidge’s veto. The exact provisions of that bill aren’t important except to note that it provided a government paid-for insurance certificate, based on one’s service pay plus interest, which a veteran could either borrow against or take as a lump-sum payment in twenty years. Not much happened for the next six years, but then as the Depression began to spread, veterans lobbied for an immediate payment of their bonus certificates. They wanted now what they were scheduled to get in 1945.

Congress responded in February 1931, again after a veto by President Hoover, by offering the veterans the opportunity to borrow more of their certificates (50% instead of the original 22½%) at a lower interest rate (cut from 6% to 4½%). Even this was not enough and the bonus issue found a powerful champion in Wright Patman, a Democratic congressman. Patman pushed for an immediate payment of the bonus, arguing that it would help restore the nation’s troubled economy. President Hoover stood firmly against any accelerated payment schedule.

The BEF was born of the veterans’ frustrations—why not carry their cause to Washington? Apparently the first plan was hatched in Portland, Oregon, in the Spring of 1931. One of the earliest to sign was Walter W. Waters, who was eventually chosen as “commander” of the BEF. The initial group of veterans, numbering less than 300, left Portland by hitching rides on boxcars in May. An “advance” man was sent ahead to drum up support for the army from local civic and veteran groups. Everything went smoothly until the contingent reached the east bank of the Missouri River at Council Bluffs, Iowa. Here railroad executives, local police, tried to end the free ride across the country. Such confrontations only attracted more national attention and in the end the 300-man Portland group was trucked across Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Maryland by each state’s National Guard.

Somewhere along the lines the veterans’ plans shifted — this would not be another march which ended once it reached its geographical objective. Instead the veterans would stay in Washington until the bonus had been paid. The idea of a national sit-in caught on and unemployed veterans from across the country began the trek to Washington. The actual number of those who arrived has been estimated at 25,000.

From what little statistical information we have, we can guess at the composition of the Bonus Army. Most were “average” workingmen who had been thrown out of work by the Great Depression. Most came from industrial states and urban areas. Most had served in the Army as privates. Although there were some Communists among the veterans, their influence was minimal. In sum, the overwhelming majority were exactly what they claimed to be—unemployed ex-servicemen, “100 percent Americans.”

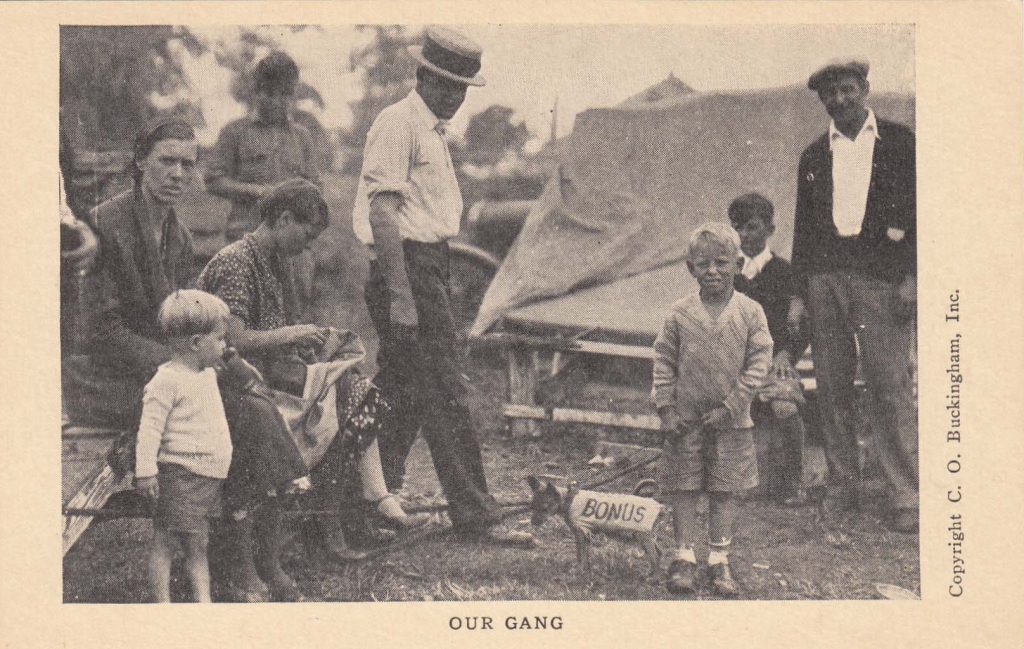

Some brought their families.

Washington would have been totally unprepared if it had not been for Brigadier General Pelham D. Glassford, the chief of the District of Columbia police force. Glassford argued that a prepared city which could feed and house the veterans would prevent riots. It was Glassford in fact who spoke to the first group of demonstrators and who suggested the formation of the Bonus Expeditionary Force. His plan was to impose a military structure on the organization and thus have clearly defined lines of authority and discipline. It worked.

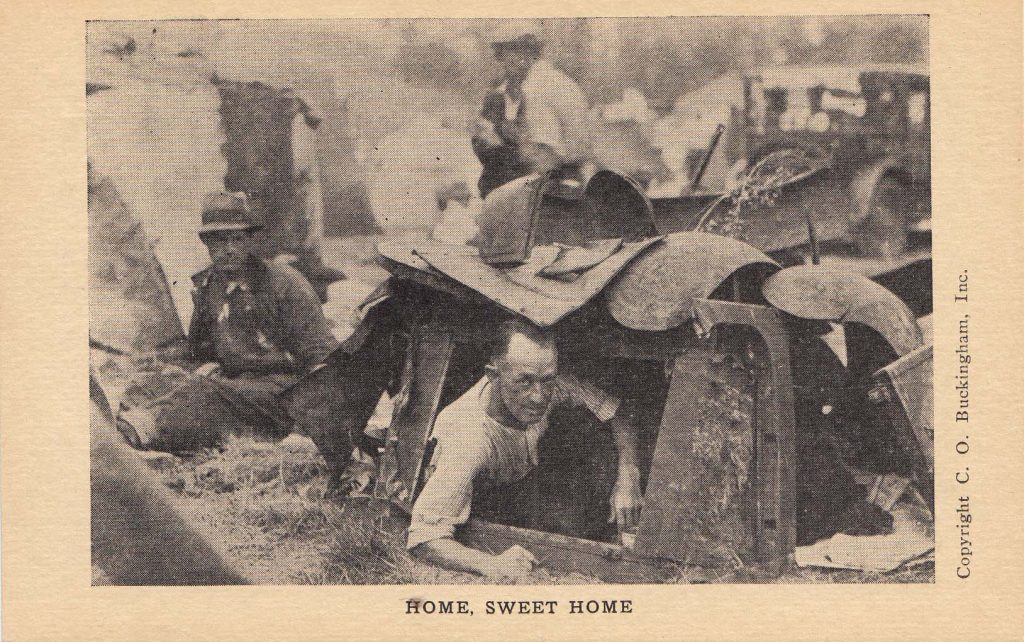

The veterans were housed in vacant buildings around the city and a main camp was established on the Anacostia Flats just across the river from downtown Washington. This site was named Camp Marks after a sympathetic police commander of a neighboring district. Food came mostly from donations. As you can see from the photographs here, shelters were constructed out of whatever material was available—tar paper, parts of old automobiles, wooden crates.

While the veterans gathered to rally support, members of Congress tried to get an immediate payment bill passed. The Senate, however, voted against the bill on June 17

th. Despite official fears, no violence took place, but the BEF did not disband and return home. Glassford was successful in getting many of the men to leave but the government was impatient and afraid and so moved to speed things up. Police were ordered to clear the veterans housed in the vacant buildings around the Capitol. On July 28 the work began but by noon hundreds of BEFers had gathered to protest the forced evacuation. Violence broke out and two veterans were killed. Hoover ordered the U. S. Army in and the story ends where we began.

Commander Walters

The political aftermath of the BEF incident was interesting. Hoover was defeated by FDR—not because of the bonus issue—but no doubt it did seriously undercut his support among veterans. During the first year of FDR’s administration the bonus was not an issue. In fact, some $300 million was cut from WWI veterans’ benefits in an economy move. Bills kept reappearing in Congress, though, and finally in January 1936 a bonus bill passed over yet another presidential veto and the veterans finally got their immediate cash payment.

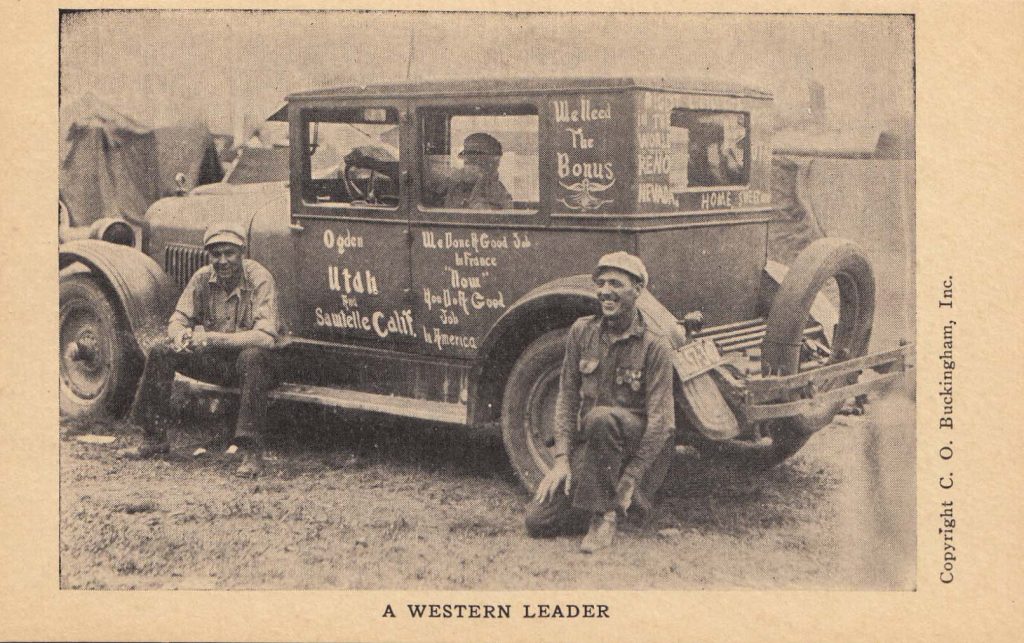

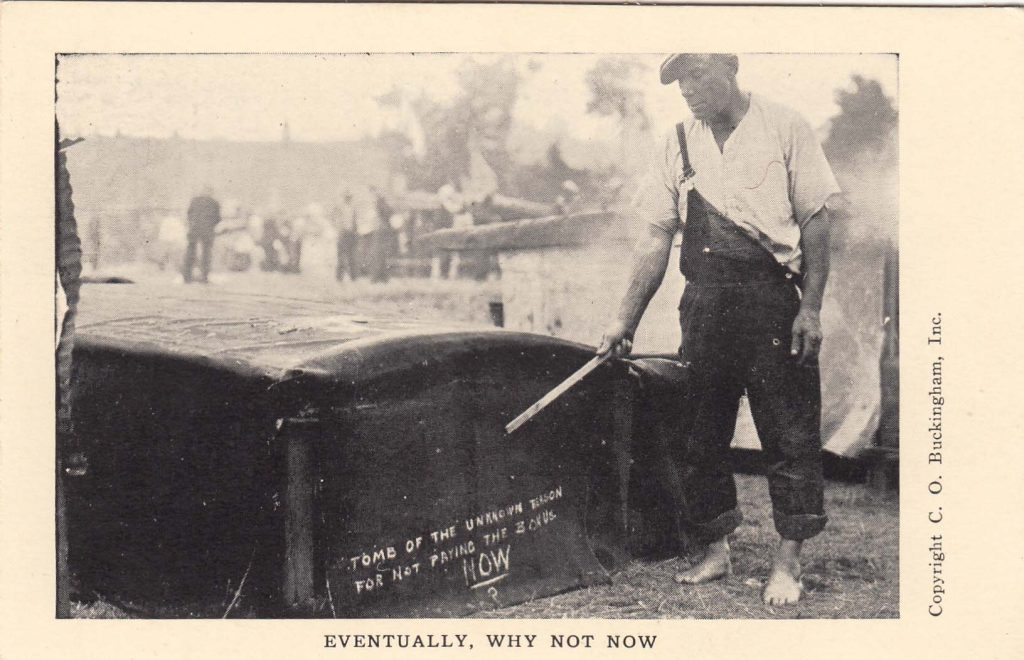

Events of the 1930s are not well documented on postcards. The postcard craze had long since passed and no doubt few people had money enough to buy cards. The nation was too preoccupied with its economic survival. The Bonus Army’s shantytown was hardly an attractive subject for view cards. So far though I’ve found two groups of cards connected with the BEF. The first is a set of commercially printed cards done by C. O. Buckingham, Inc. These black and white half-tones on a cream-colored stock were published by Clinton O. Buckingham, 19 T Street NE, Washington, D.C. Twenty-two titles are known, all of which are views of life at Camp Marks. The Camp and its residents were favorite subjects of photographers.

Checklist of the C. O. Buckingham Cards

- BA1 Camp Marks, Washington

- BA2 Caught Without a Spare

- BA3 Chow

- BA4 A Company Street

- BA5 Daydreams (Bonus)

- BA6 Eventually, Why Not Now

- BA7 Every Day Is Wash Day

- BA8 Home, Sweet Home

- BA9 Looking Them Over

- BA10 Maryland Company St.

- BAH Model “T” Apartments

- BA12 Next

- BA13 No Dancing Here

- BA14 Our Gang

- BA15 Quartermaster

- BA16 Roof Gardens

- BA17 Same Old Stuff

- BA18 Six Merry Hatters

- BA19 Southern Style

- BA20 Until 1945

- BA21 A Western Leader

- BA22 What Have You

In his autobiographical account

BEF: The Whole Story of the Bonus Army, Commander Waters observes: “Any camera that was set up within a hundred feet of the camp attracted a rush of men. One way to have gotten the BEF out of town would have been to send all the camera men, like a league of Hamelin pipers, ten miles out of town and to have ordered them to set up their cameras.”

I thought for a while that the BEF might have used post cards as a way of propagandizing their cause, but I’ve found no evidence to support the idea. Waters does not mention postcards, although he does write about how businessmen tried to get the BEFers to sell “foot powder, badges, booklets.” I read through the few surviving issues of

The B.E.F. News, a short-lived camp newspaper, but again no mention of postcards appears. I’ve seen no other views of the Washington demonstration—no protestors gathered on the streets, no cartoons, no view of the Army’s action.

The second group of cards are real photocards showing the encampment at Johnstown, Pennsylvania—generally misspelled Johnston. Considering the fact that the BEFers were there only nine days—from July 29th at the earliest to August 6th at the latest—these are probably even more remarkable. Three of this group carry the name Doubleday, perhaps the photographer, but if so, he was apparently not a local one.

The BEF was born of the veterans’ frustrations—why not carry their cause to Washington? Apparently the first plan was hatched in Portland, Oregon, in the Spring of 1931. One of the earliest to sign was Walter W. Waters, who was eventually chosen as “commander” of the BEF. The initial group of veterans, numbering less than 300, left Portland by hitching rides on boxcars in May. An “advance” man was sent ahead to drum up support for the army from local civic and veteran groups. Everything went smoothly until the contingent reached the east bank of the Missouri River at Council Bluffs, Iowa. Here railroad executives, local police, tried to end the free ride across the country. Such confrontations only attracted more national attention and in the end the 300-man Portland group was trucked across Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Maryland by each state’s National Guard.

Somewhere along the lines the veterans’ plans shifted — this would not be another march which ended once it reached its geographical objective. Instead the veterans would stay in Washington until the bonus had been paid. The idea of a national sit-in caught on and unemployed veterans from across the country began the trek to Washington. The actual number of those who arrived has been estimated at 25,000.

The BEF was born of the veterans’ frustrations—why not carry their cause to Washington? Apparently the first plan was hatched in Portland, Oregon, in the Spring of 1931. One of the earliest to sign was Walter W. Waters, who was eventually chosen as “commander” of the BEF. The initial group of veterans, numbering less than 300, left Portland by hitching rides on boxcars in May. An “advance” man was sent ahead to drum up support for the army from local civic and veteran groups. Everything went smoothly until the contingent reached the east bank of the Missouri River at Council Bluffs, Iowa. Here railroad executives, local police, tried to end the free ride across the country. Such confrontations only attracted more national attention and in the end the 300-man Portland group was trucked across Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Maryland by each state’s National Guard.

Somewhere along the lines the veterans’ plans shifted — this would not be another march which ended once it reached its geographical objective. Instead the veterans would stay in Washington until the bonus had been paid. The idea of a national sit-in caught on and unemployed veterans from across the country began the trek to Washington. The actual number of those who arrived has been estimated at 25,000.

From what little statistical information we have, we can guess at the composition of the Bonus Army. Most were “average” workingmen who had been thrown out of work by the Great Depression. Most came from industrial states and urban areas. Most had served in the Army as privates. Although there were some Communists among the veterans, their influence was minimal. In sum, the overwhelming majority were exactly what they claimed to be—unemployed ex-servicemen, “100 percent Americans.”

From what little statistical information we have, we can guess at the composition of the Bonus Army. Most were “average” workingmen who had been thrown out of work by the Great Depression. Most came from industrial states and urban areas. Most had served in the Army as privates. Although there were some Communists among the veterans, their influence was minimal. In sum, the overwhelming majority were exactly what they claimed to be—unemployed ex-servicemen, “100 percent Americans.”

While the veterans gathered to rally support, members of Congress tried to get an immediate payment bill passed. The Senate, however, voted against the bill on June 17th. Despite official fears, no violence took place, but the BEF did not disband and return home. Glassford was successful in getting many of the men to leave but the government was impatient and afraid and so moved to speed things up. Police were ordered to clear the veterans housed in the vacant buildings around the Capitol. On July 28 the work began but by noon hundreds of BEFers had gathered to protest the forced evacuation. Violence broke out and two veterans were killed. Hoover ordered the U. S. Army in and the story ends where we began.

While the veterans gathered to rally support, members of Congress tried to get an immediate payment bill passed. The Senate, however, voted against the bill on June 17th. Despite official fears, no violence took place, but the BEF did not disband and return home. Glassford was successful in getting many of the men to leave but the government was impatient and afraid and so moved to speed things up. Police were ordered to clear the veterans housed in the vacant buildings around the Capitol. On July 28 the work began but by noon hundreds of BEFers had gathered to protest the forced evacuation. Violence broke out and two veterans were killed. Hoover ordered the U. S. Army in and the story ends where we began.

Always a welcome sight when the postcard articles appear in my mailbox. I wonder if the authors of these articles get paid? This particular one required research and lots of energy to produce. Grateful for those that keep it running! What a delight it is in my world.

Both of these are interesting series to collect, and this background history here is remarkable, and good to read again. Thanks very much for all of this social history!!

The idea of turning cars into rolling advertisements for the cause obviously caught on!

At the time this article was presented I had not been leaving comments on the site, but after reading this again more thoroughly I had to leave a comment. This was a great piece of story telling of a significant American event, I am sure there are many people today who are completely unaware of this bit of U.S history. Thankyou for your time and effort towards this article.