Tanglewood

Evening at Pops and Evening at Symphony were two Public Broadcasting System programs that aired between 1970 and 2004. These programs were very popular but extremely expensive. The average cost of each program often exceeded one million dollars. To account for the high numbers consider that salary and performance fees for nearly 250 people would run well into the high six-figures. The Pops Orchestra had more the 90 members, the Symphony Orchestra had 108 members, there were executive producers, producers, camera operators, audio controllers, and an auxiliary staff of another 40 to 50 people.

These programs were usually performed at Symphony Hall in Boston and taped for later broadcast. However, through the years at least three episodes were taped performances at Tanglewood, the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s summer home in Lenox, Massachusetts.

Lenox is an especially beautiful town in the Berkshire Mountains of western Massachusetts, with a population of just 5,100. [Some of the vistas and stately Lenox homes are presented in an unusual twelve-card set (#2356) by Tuck.]

Tanglewood

In the summer of 1934 a “festival committee” in the Berkshires hired musicians from New York to perform three concerts. The concerts were extremely popular, and it was decided to repeat the festival in 1935. The 1935 invitation went to Serge Koussevitzky and the Boston Symphony.

In the evening of August 13, 1936, the BSO gave its first concert in the Berkshires. More than fifteen thousand listeners gathered in a large tent and on the lawns around it to hear the two-hour program.

The 1936 concerts attracted even larger crowds. In the winter of 1936, two women from the Tappan family of Boston, Ellen Shepherd Brooks and her aunt, Mary Aspinwall Tappan, offered Tanglewood on the north shore of Mahkeenac Lake to the Boston Symphony Orchestra for their summer headquarters. The estate was 210 acres of lawns and meadows given in its entirety to Koussevitzky and the orchestra.

The donation was announced on February 15, 1937, in plenty of time to prepare a series of summer events. On August 5, 1937, the festival opened under a tent for the first Tanglewood concert, an all-Beethoven program.

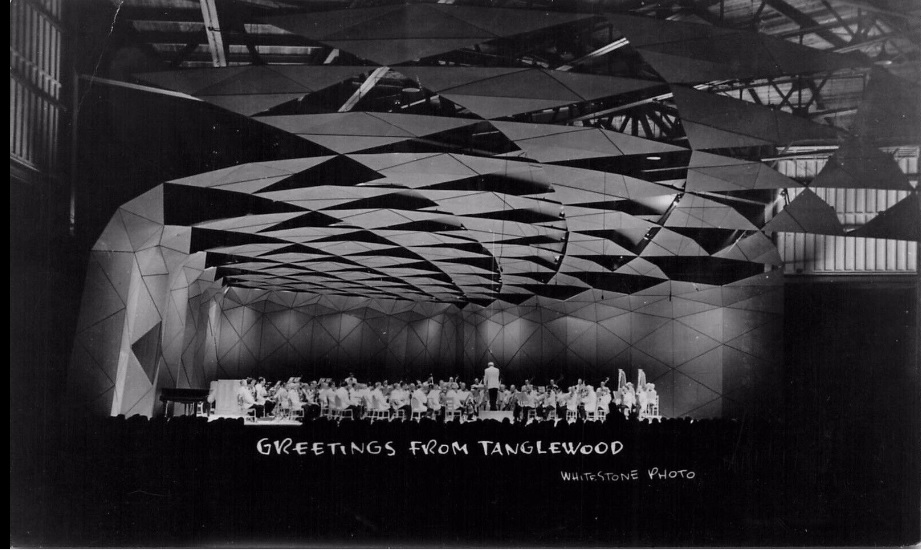

After the 1937 festival, the trustees of the BSO asked the Stockbridge (Massachusetts) engineer Joseph Franz to erect a music shed and with little fanfare he managed an affordable enclosure with excellent acoustics and “lots” of fresh air. It was opened on August 4, 1938, and is still in use with only minor modifications. For its fiftieth anniversary in 1988, the structure was rededicated as “The Serge Koussevitzky Music Shed.”

* * *

The conductors who made Tanglewood famous

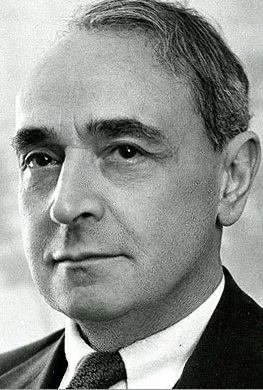

Koussevitzky (above) was a Russian-born conductor, composer, and double-bassist. He was music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 1924 to 1949. Known only as “Maestro” to his colleagues, he was “Serge” to his family and friends. His wife Natalie died in 1942. It could be said that he devoted the last decade of his life to Tanglewood and the Koussevitzky Music Foundation that he founded in her honor. The “maestro” died in Boston in 1951 and was buried alongside his wife in the cemetery of the Church on the Hill in Lenox.

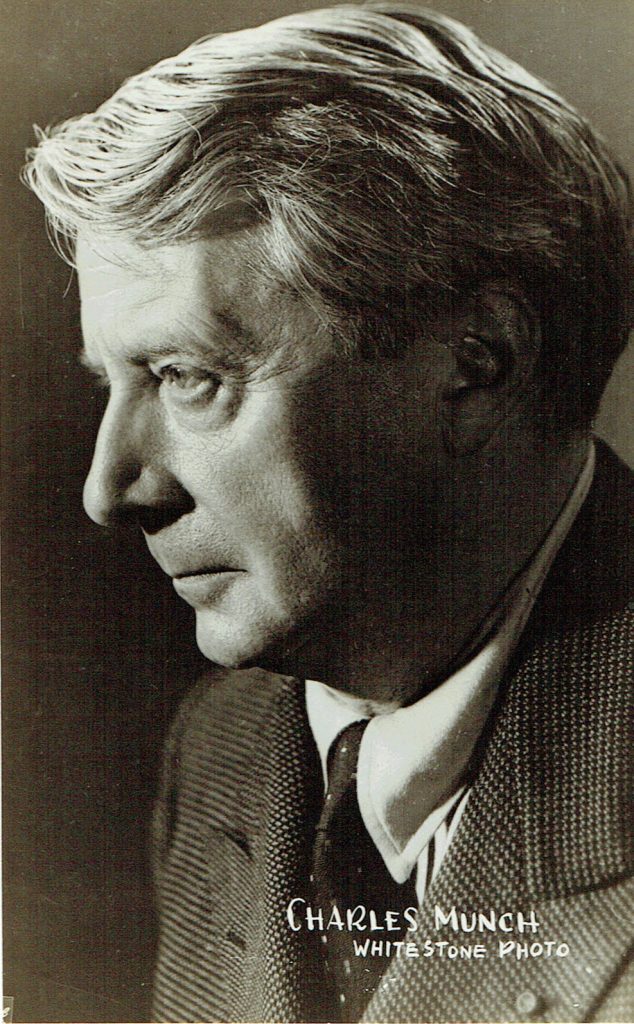

Charles Munch was a French violinist and conductor. His musical specialty was the French symphonic repertoire including the works of Saint-Sean, Ravel, Debussy, and Poulenc. His years in America were his most memorable. He served as music directors for three orchestras but is best known for his years (1949 to 1962) in Boston.

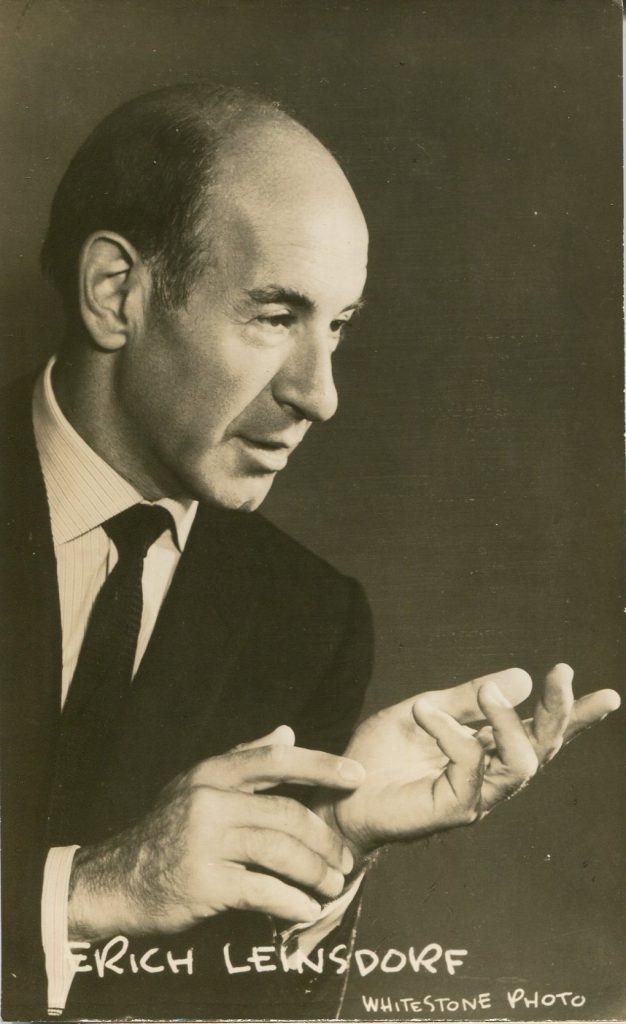

Erich Leinsdorf followed Munch as music director in Boston in 1963. He stayed only seven seasons, but each one was marked by controversy and dispute, often serious. His occasional clashes with musicians and administrators were notorious but his recordings for RCA were hailed as some of the best of the era.

On Friday, November 22, 1963, Leinsdorf was forced to announce the assassination of John F. Kennedy at a matinee concert. Without missing a beat, he followed his announcement with a performance of the Funeral March from Beethoven’s Third Symphony.

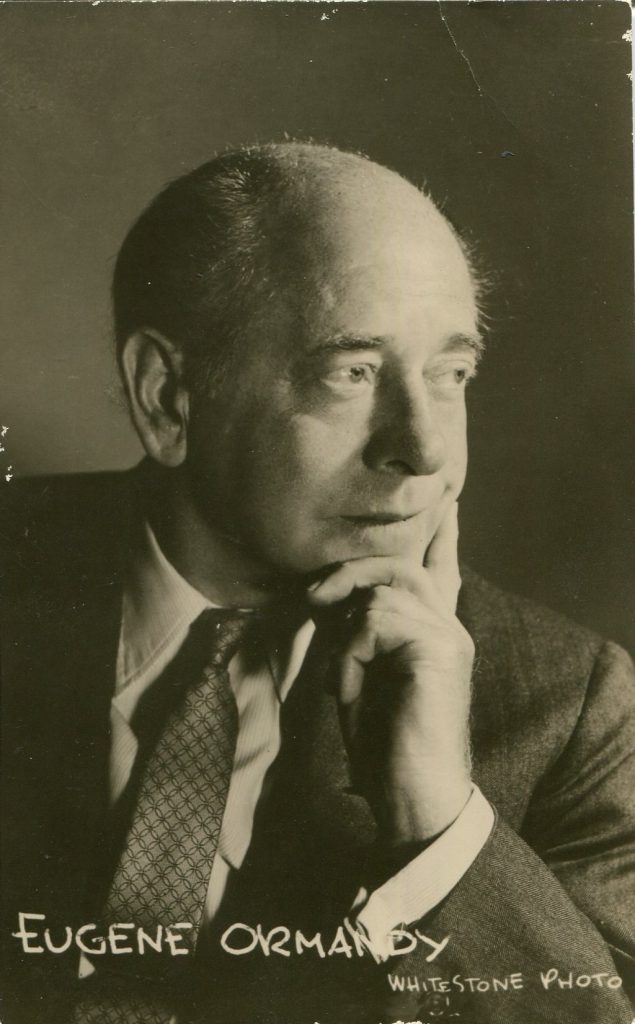

Eugene Ormandy, known as the Meticulous Maestro, was legendary for his no-nonsense conducting. He was born in Hungary, studied as a violinist and came to America in 1921. He first worked as a violinist in the Capital Theatre orchestra in New York City. When the breaks came, he took full advantage and by 1931 had earned a reputation as a competent conductor. After he substituted for the renown Arturo Toscanini, he gained favor quickly an assumed the leadership of the Minneapolis Symphony in 1931. He joined the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1936. Ormandy’s 44-year association with the Philadelphia Orchestra was the longest enjoyed by any conductor with any American orchestra.

The best Ormandy story comes from his pre-Philadelphia days in Minneapolis. The American composer, Roy Harris, chose the Minneapolis to record his new overture called “When Johnny Comes Marching Home,” but the music did not arrive until the morning of the recording session. The normally even-tempered Ormandy was in a rage. He looked over the score at breakfast and then for a while after. Still angry, he threw the score on the floor, got in his car and drove off to the recording session. He conducted the overture from memory.

The day after his death in 1985, Ormandy’s obituary concluded with, “… if the great conductors of this century are like generals, then perhaps Toscanini was like Clausewitz, Beecham like Montgomery and Stokowski like Patton. But Ormandy, who died yesterday at age 85 from pneumonia, was like Ike.”

Ormandy was one of the few American conductors who worked just as hard in the summer as they did during their annual season of performances. He spent several weeks each summer at the Philadelphia Orchestra’s two summer venues: Robin Hood Dell in Fairmount Park and the Saratoga Festival in upstate New York. He also spent one weekend each year at Tanglewood. His concerts sold-out every performance for eleven years.

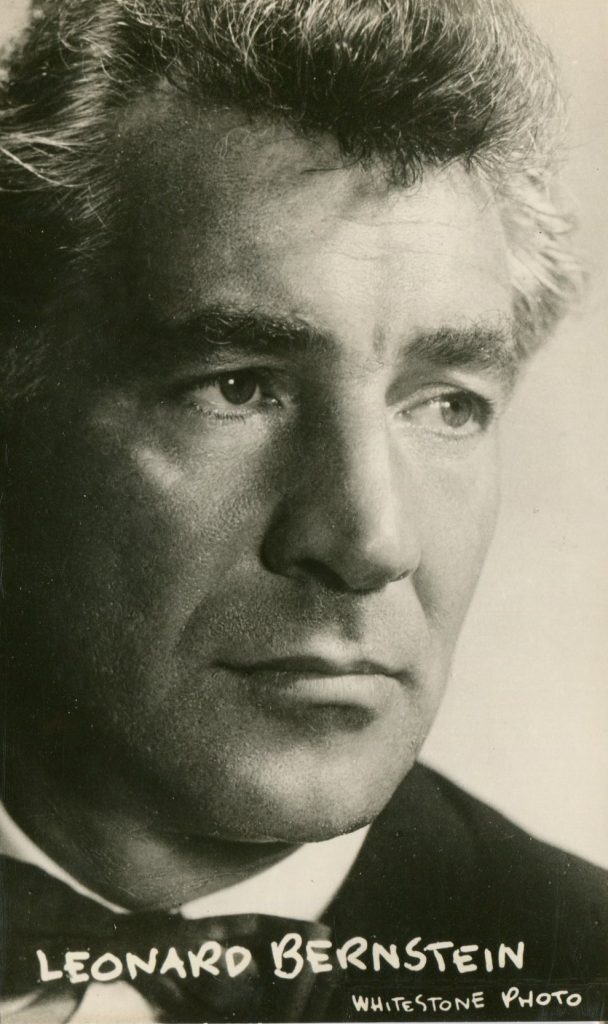

Leonard Bernstein, like Ormandy came to fame when he substituted for an ailing colleague. Early in the 1943-1944 concert season Bernstein was appointed assistant conductor to Artur Rodzinski of the New York Philharmonic. On November 14, 1943, Bernstein made his conducting debut on short notice and without a rehearsal. The guest conductor was to be Bruno Walter, but on that Sunday morning he awoke seriously ill and was forced to cancel. Bernstein got an early morning call to conduct a very challenging program. (It is probably a myth, but it has been told that the call came while he was still in bed that Sunday morning.)

The Monday morning edition of The New York Times carried the story on its front page and remarked in an editorial, “It’s a good American success story. The warm, friendly triumph of it filled Carnegie Hall and spread far over the air waves.”

From personal experience, I can testify to Leonard Bernstein’s expertise in his work at Tanglewood and particularly with regard to his interpretations of Gustav Mahler’s symphonies. I witnessed Bernstein conduct three Mahler symphonies (the 1st, The Titan in D-major (1888); the 2nd, The Resurrection in C-minor (1895), and the 5th, (1904) which opens with a trumpet quote from the Trauermarsch (Funeral March) used by the Austro-Hungarian Army – all impeccable, all memorable and brilliant.

I attended a concert at Tanglewood in July of 1980. Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony was one of the orchestral works played that day. During the symphony, I heard a rumble and turned to my friends and said they’ve come in too early with the thunder storm. Then there was a second, louder rumble, and we realized it was a real thunder storm, not the one Beethoven set to music. A few minutes later, the sky opened with a torrential downpour, Fortunately we were under the shed and not seated out on the lawn. I’d been to major league baseball games with… Read more »

Tanglewood is one of my favorite places to hear glorious music (and I own many postcard views of the shed and lawns). I think Maestro Seiji Ozawa’s long tenure as music director of the BSO (1973-2002) might be noted here. Ozawa Hall, a smaller venue for chamber ensembles and recitals, opened on the Tanglewood grounds in 1994 and was named in his honor. Oh, and by the way, a thunderstorm will still cause the music to stop temporarily while everyone on the lawn takes shelter under the roof of the shed.

I remember Arthur Fiedler was the conductor of the Boston Pops during my early years.

I have most of those postcards, and autographs of the artists