George Miller

The Kodak Model 3A Postcard Camera

and the Velox Postal

The popularization of an art form or a technology is seldom a serious subject of scholarly interest. For example, historians of photography study the unusual — the gifted photographer, the photograph that is a work of art — not the ordinary or the popular. The ultimate criticism in a photography course is to refer to someone’s photographs as “snapshots.” Because of this understandable bias, it is often difficult to locate information about anything that appealed to or was intended for a large popular audience. Such things might offer interesting stories in the history of marketing or business, but they do not seem worthy of serious study. A good case in point is the popularization of photography. Little has been written about the history of George Eastman’s attempts to put photography within the reach, both financially and technically, of every person in America. Even less has been written about the role of the real photograph postcard in achieving that goal. In fact, the subject is never mentioned in any history of photography. My thesis is simple: the postcard craze during the period from 1905 to 1915 was a major force in the growth of amateur photography in America. Kodak and other manufacturers knew that and marketed and developed products to foster the inter-relationship.

1. Point the camera 2. Press the button 3. Turn the key 4. Pull the cord

The small, simple, lightweight Kodak had a fixed focus lens (everything beyond 8 feet was in focus), one speed, and one lens opening. In other words, the amateur photographer literally pointed the camera and pushed a button, it was not necessary to figure out how to focus the camera or adjust for the amount of available light. Not only did Eastman simplify the operation of the camera, he also eliminated for the amateur the complex process by which the film was then developed and printed. After making the 100 exposures possible on the roll of film, the amateur photographer just mailed the entire camera back to the factory where the film was removed, developed, and printed (or enlarged). A new roll was loaded at the factory and the camera and mounted prints were returned to the customer. Eastman’s invention created the “snapshot.” Essentially, the snapshot was an art-less photographic record of the important moments in anyone’s life. In the draft of the original “user’s” manual, Eastman continued: “Photography is thus brought within the reach of every human being who desires to preserve a record of what he sees. Such a photographic notebook is an enduring record of many things seen only once in a lifetime and enables the fortunate possessor to go back by the light of his own fireside to scenes which would otherwise fade from the memory and be lost.” The Kodak Model 3A The link between Eastman’s simplified technology and the postcard came with the introduction of the Model 3A Folding Pocket Kodak. Marketed first in May 1903, the Model 3A was Kodak’s first postcard camera, that is, a camera designed to take postcard-size negatives (3¼-inches by 5½- inches). The Model 3A was an extremely popular camera in large part because it provided the average person with a relatively inexpensive camera with which to make real photo postcards. The original Model 3A underwent numerous changes until 1915. A variety of related models with special features were also introduced, including a Special Kodak No. 3A (with a compound shutter) in 1910; an Autographic Kodak No. 3A (a write-on-the-film camera) in 1914; and a Pocket Kodak No. 3A in 1927. Taking pictures with a 3A The Model 3A used a “122 film,” a rolled film backed with paper. The negative that it yielded measured 3¼-inches by 5½-inches. By today’s standards that is a monster negative. For a contrast, think of how small the negatives are from a disc camera. These dimensions coincided with the standard measurement of a postcard. Any negative from a Model 3A could be printed on a piece of postcard-sized developing paper by a simple contact process — that is, the negative was placed on top of a piece of unexposed developing paper and then both were exposed to light. If was not necessary, for example, for the image to be enlarged since the contact print was the exact size of the negative. The larger negative also meant that more detail could be captured. That is one of the reasons why the images of real photocards are often so sharp and detailed. Unlike the original Kodak, the Model 3A offered a set of adjustments. The time or length of exposure could be set for “instantaneous” (measured in 1/25, 1/50, or 1/100 of a second), “time” (shutter would remain open as long as desired), or “bulb” (shutter would remain open as long as a bulb was squeezed). The lens opening could be adjusted to allow more or less light to enter the camera, and the distance between the camera and the subject could be changed (from 6 to 100 feet). Indoor photography and flashed light pictures It was possible to take photographs indoors without additional flash illumination only with a very long exposure time. For example, in a room with “dark colored walls and hangings and only one window” on a “cloudy dull” day (admittedly an extreme example), the manual recommended an exposure time of 5 minutes and 20 seconds. For best results in 1910, the amateur photographer relied on “Eastman Flash Sheets.” The chemically treated sheets were fastened in a holder and then ignited by touching them with a match. The camera’s shutter was left open until after the sheet had flashed and the exposure was made. The photographer then closed the shutter and advanced the film for the next picture. Obviously flash photography required a patient sitter who could hold a pose until the entire procedure had been completed. Developing and printing By the time that the 3A had gained popularity, Eastman was marketing a wide range of supplies for the amateur photographer who wished to develop and print their own photographs. In 1913, for example, a complete home developing outfit — a red candle lamp, trays and tools, chemicals, and a contact printing frame — could be purchased for $1.50.

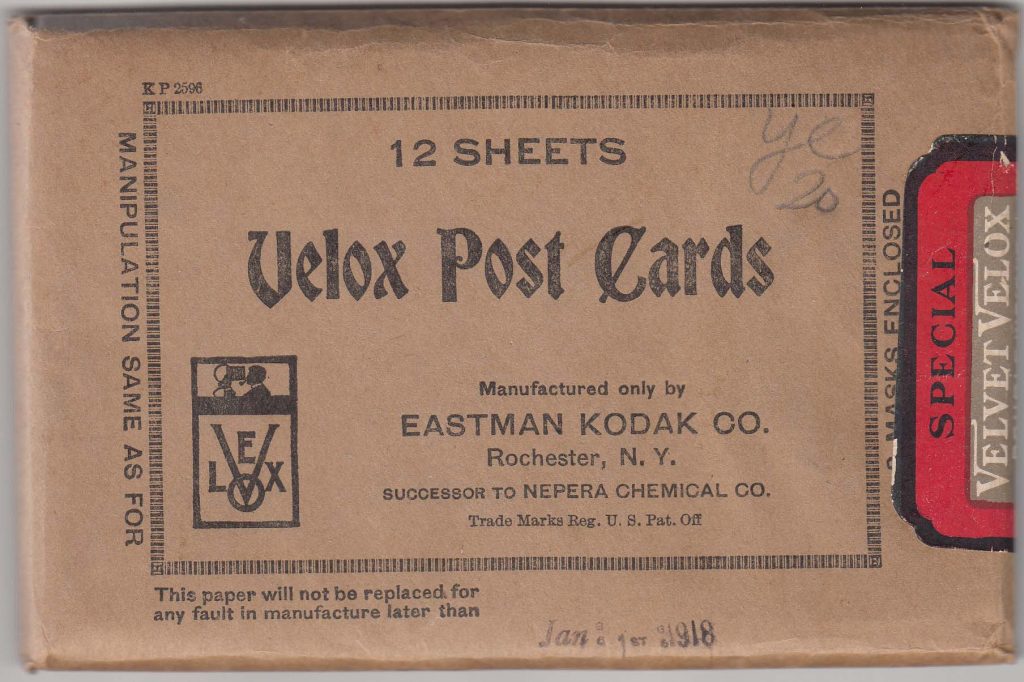

An envelope for Velox Post Cards developing paper, also marketed by Kodak.

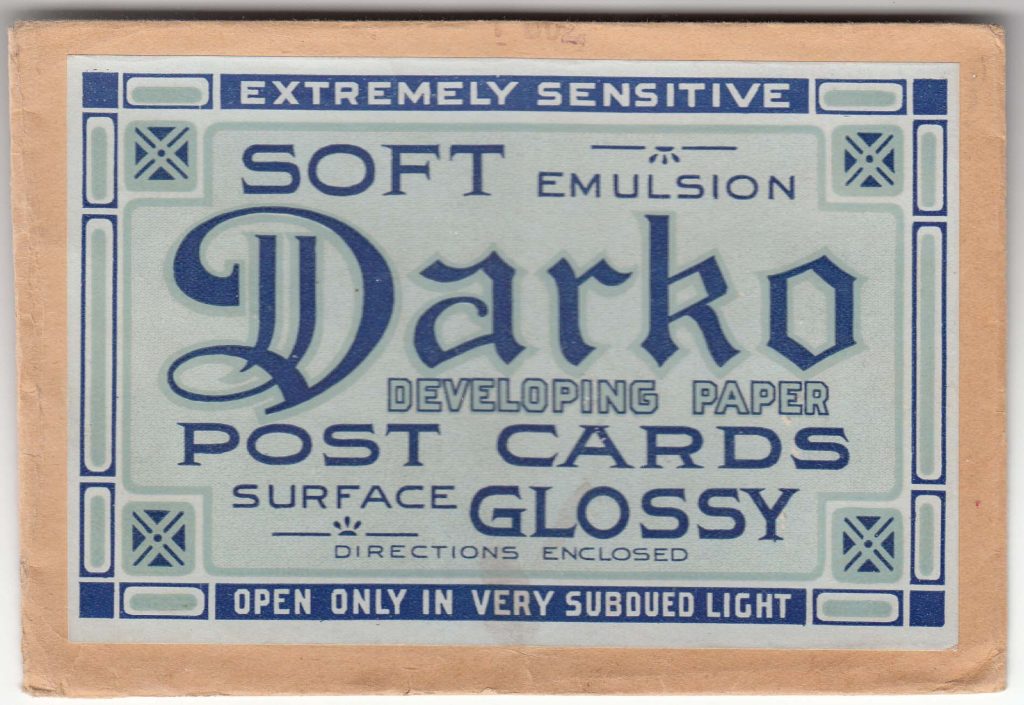

An envelope for DARKO postcard developing paper. Dated 1916.

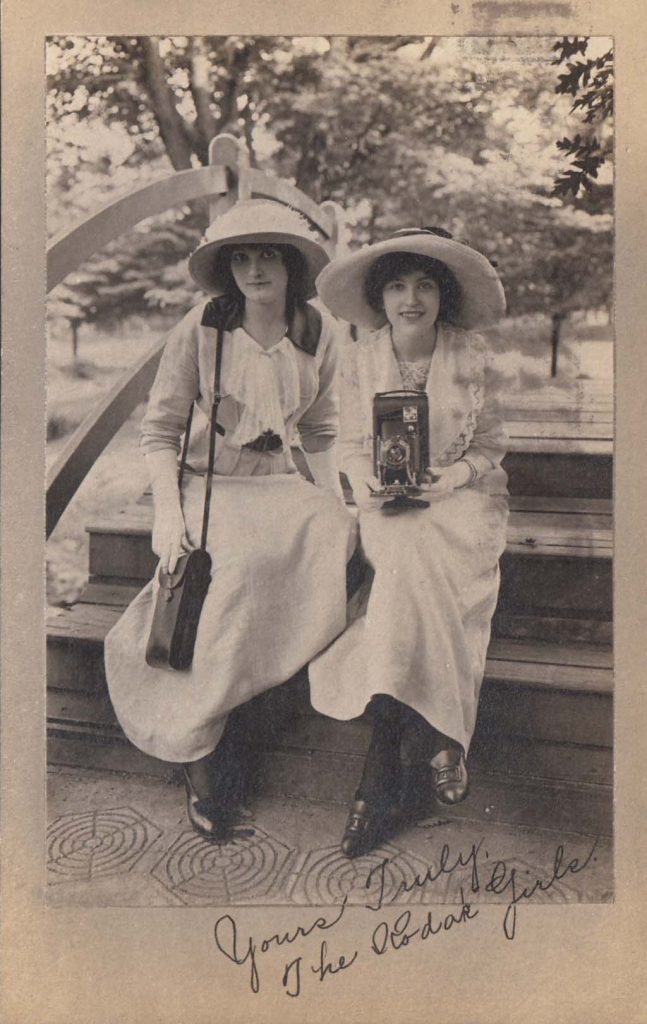

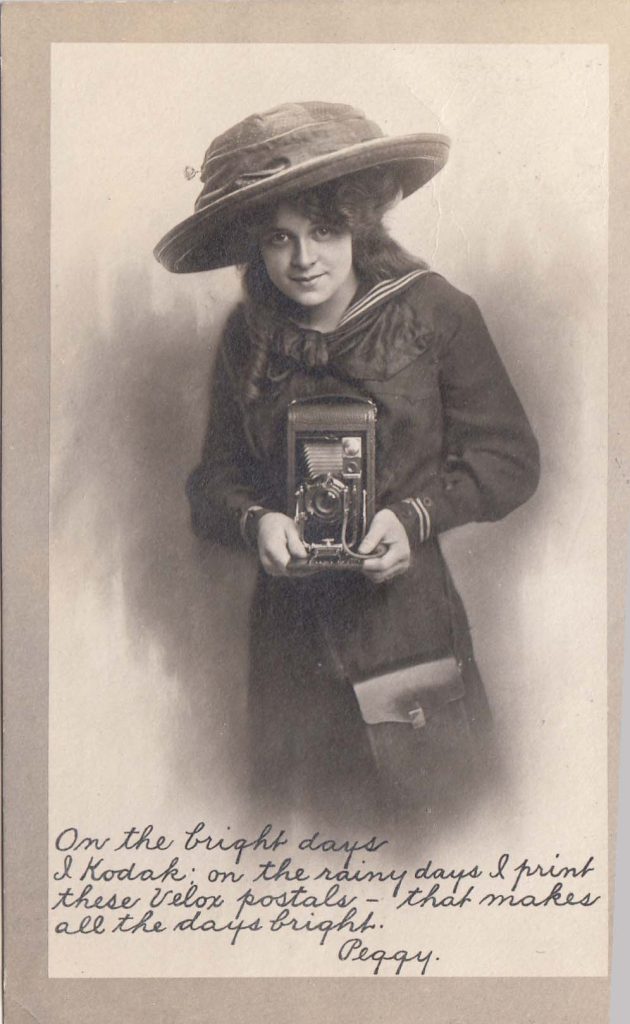

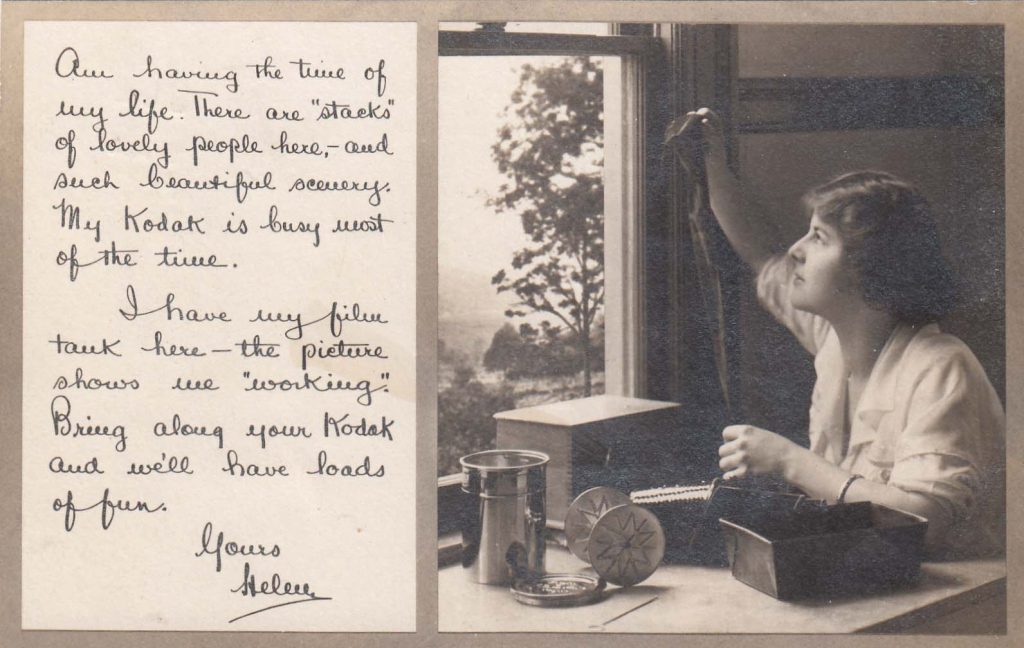

Eastman recommended printing the film negatives on Velox Developing Paper. First introduced in 1889, Velox was the original “gas-light” developing paper. Although Velox prints could be made by exposing the negative and paper to daylight, the varying intensity of natural light made it simpler and more reliable to print by artificial light—most typically by light from a gas burner (hence the “gas-light” paper). Many more homes after all were illuminated by gas than by electricity. A print could be made by placing the negative and developing paper together in the print frame and then positioning the frame seven inches from the source of artificial light for anywhere from 10 to 40 seconds. As those figures suggest, Velox paper was so slow (insensitive to light) that it did not require a darkroom. In fact, it could be handled without fear of exposure as long as it was 10 feet away from an ordinary gas flame. Today, of course, developing paper must be handled in total darkness. The amateur photographer Everything about the Model 3A and the Velox postals was designed to appeal to the average person who did not want to make complex decisions about the proper exposure, who did not have access to a dark room, or who did not want to use complicated developing and printing technologies. The idea was never to create a work of art; the idea was to capture reality to be shared with friends (hence the postals). The simplified camera and chemical procedures did not appeal to the serious photographer. They were too limiting. For all of the splendid real photocards that survive, the fact remains that they are the work of talented (or lucky) amateurs or of small-town photographers who sought an additional market for their photographs. That it promoted the amateur “snapshot” should be a point in favor of the Kodak Model 3A and the Velox postal. After all, great art always transcends its age, it is untypical and generally unpopular. The popular and the serious merely fulfill two different functions, one allows us to look back at ourselves and see what we have been and what we have experienced; the other allows us to look beyond the limits of our day-to-day existence and challenges our perceptions and values. * * * Sample Kodak Advertising Postcards Kodak promoted its Model 3A cameras and Velox postals through a series of advertising postcards — each of which was itself a Velox postal. The examples reproduced here date from 1909 to 1914. Each card features a pre-printed handwritten message on its front and a pre-printed handwritten advertisement on its back. The cards were apparently made available to local Kodak distributors who could also have their addresses added to the back message. The cards represent a perfect example of how closely the postcard craze and the popularization of photography were interlinked.

e this) to the people at home. You can do it all. No dark room. Simple all the way. Let us show you.”

e this) to the people at home. You can do it all. No dark room. Simple all the way. Let us show you.”

Thank you for such a detailed description of the “how to” of this process. In the late 1950s, I had a darkroom set up in the bathroom and made postcards that I could send out. It was laborious and I would have loved these send-away cards that Kodak offered. Things do not always get better over time.

Great article, thank you. I got into “real photo” postcards, big time, less than 2 years ago. It started as the off-shoot of another collection…vintage sand pails for display at our beach cottage in Lewes, Delaware. I bought RPPC cards of kids with sand pails, and mounted them around my display. These are mainly studio shots from the 1908-20 period, even though my pails are 1932-59. I now collect RPPCs of trains at/near a depot, and 1908-20 kid portraits. As far as the kids go, I find them fascinating because they have their entire adult life ahead of them, yet… Read more »

Incredible article chock full of information!

I’m not sure if it’s a Velox Postal, but one of my cards is a photo of my great-uncle taken when he was training at National Cash Register in Dayton, Ohio. Obviously a limited edition — I wonder if any other examples survive.

The photographer or company likely sold or gave each of the “subjects” a set number of postcards that they would then proudly have sent off to friends and relatives.

I am an avid collector of real photo post cards. Something the author didn’t mention is the loads of local historical information that can be gleaned from the cards. For many small towns these cards are the only printed history available. Great article.

Very interesting and informative article. The degree to which photography (and RPPC photography in particular) was marketed to women is intriguing.

Excellent informative article, thank you for republishing it.

Great article! I have been working on a project for a local museum about postcards in their collection, many of them from the last quarter of the 19th century and first half of the 20th century. Most of the postcards were purchased but some have the amateur’s touch. Those often seem to tell a far more interesting story about daily life, events that captured people’s attention in their town, the home scene, etc.

where do you read the May 1903 date? I ask because there’s what appears to be Kodak real photo post cards mailed earlier than that. … and thank you for your site. I’ll have fun reading it