Nathaniel Dancer

Arches, A Series, Part II

L’Arc de Triomphe, Paris, France

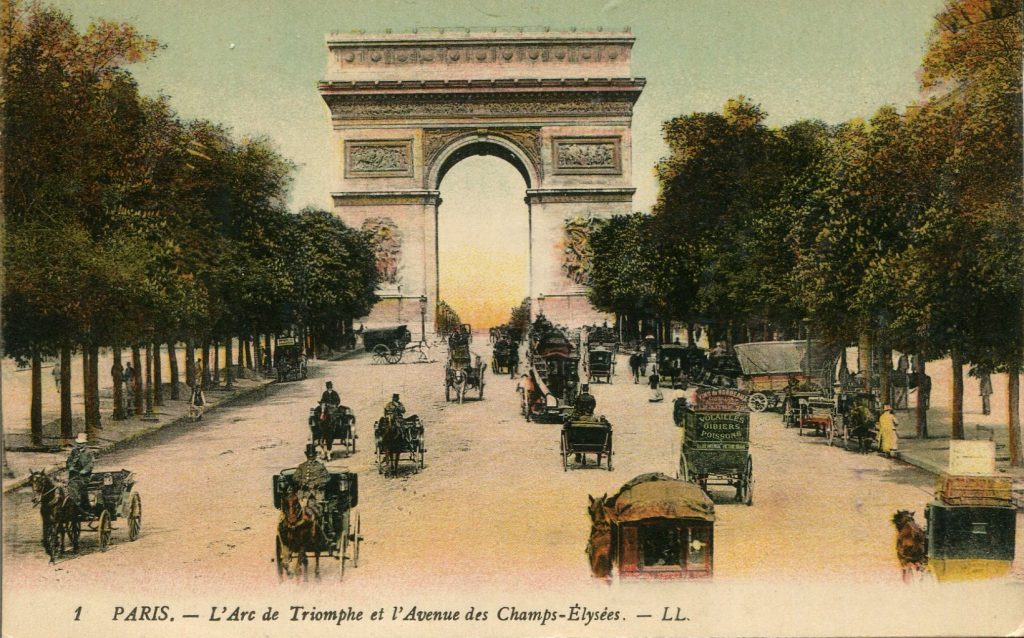

When Lucian Levy (he is the LL at the end of the caption on literally millions of French postcards) opened his business in Paris, he hired photographers who would travel the continent to photograph whatever they saw. Do you see the number on this card?

It is #1. It is likely the first photograph taken by the Levy staff photographers. There is no other significance in the number, but it is interesting that the first postcard Levy published happened to be the most famous of all Paris landmarks.

The Triumph Arch is located at the L’étoile (the star), an intersection of twelve major thoroughfares that divide the Paris neighborhoods. In Scotland such neighborhoods are called districts; in America and Canada they are wards; and in many places such constituencies are called provinces.

Construction of the Arch began in 1806 when it was commissioned by Napoleon. My studies have not unveiled other reasons for the delay except the obvious one previously established, to wit, the primary architect, Jean Chalgrin died one year into the project and construction was abandoned.

In 1833, during the reign of Louis-Philippe (the last King of France), Chalgrin’s successor, Jean-Nicolas Huyot was appointed. In 1807, the young Huyot was the first architectural student to win the Prix de Rome (a French scholastic prize that permitted study for up to five years in Rome). After his stay in Italy, he continued to study in other countries before returning to Paris in 1822 to accept a position at the French Academy of Fine Arts. Among his students were three later winners of the Prix de Rome.

After his appointment, Huyot was slow to dedicate his attention to the continuance of work, but still managed to complete the Arch by July 1836 – just months after you Americans fought over the Alamo in Texas.

Two favorite sons of France have been subject of special honors at the Triumph Arch. The first was Napoleon himself. In the autumn of 1840, the king made a royal decision that provided for Napoleon’s return to Paris. He died at Saint Helena fifteen years after he ordered the construction of the Arch. Saint Helena is a 47 square-mile island in the South Atlantic Ocean. Napoleon’s body rested there until 1840 and after an exhumation that required almost 500 men to complete, his remains were loaded aboard a ship for the six week journey back to France. The entourage arrived in Cherbourg where crowds of thousands came to pay their respects to the former Emperor. The journey was completed aboard river-barges up the Seine River to Paris. On December 15, his remains passed under the arch before burial at Les Invalides.

For generations, Paris has been the epitome of all things cultured: art, literature, sculpture, fashion, and cuisine. For many of the French, Victor Hugo was the essence of late 19th century Paris. Perhaps an unlikely hero, but nevertheless, prior to his remains being buried in the Pantheon, Hugo lay-in-state under the Arch during the night of May 22, 1885.

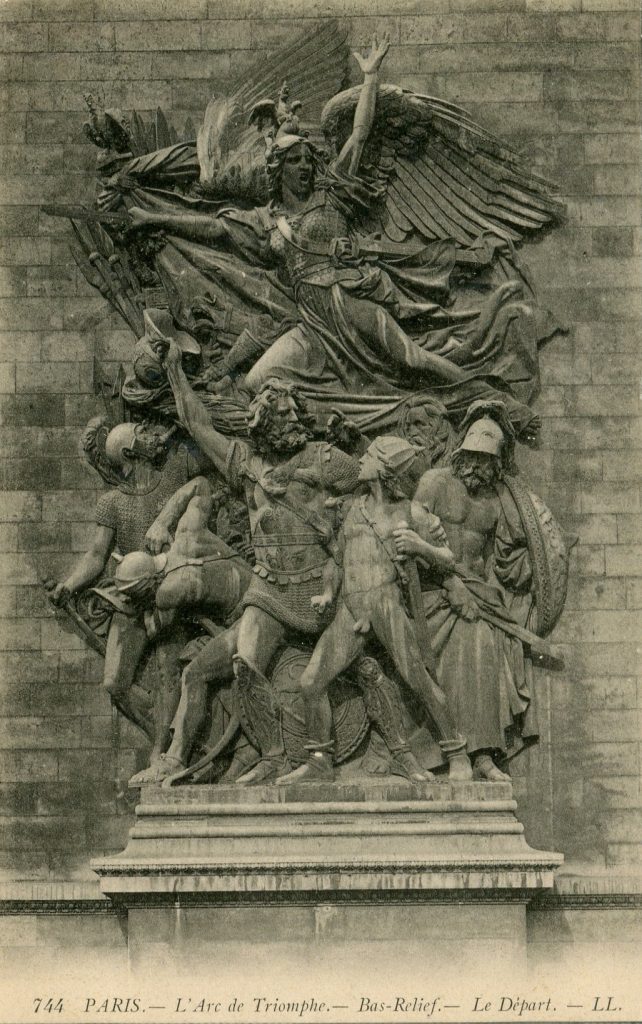

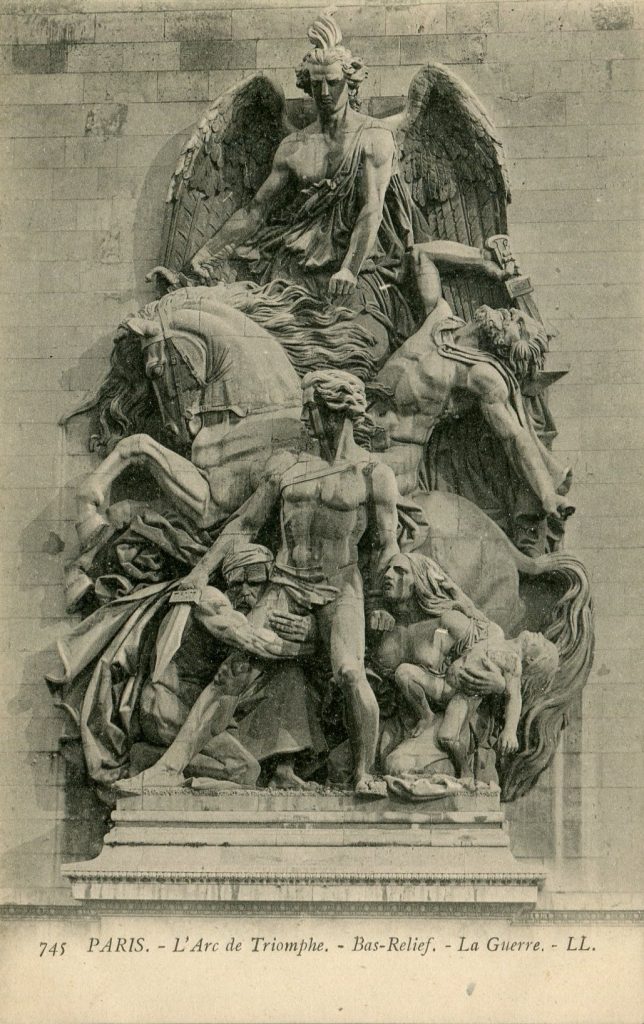

As any good architecture student can tell you, four pillars are required to construct a worthy arch. The Triumph Arch is no exception, and each pillar is a setting for honorary sculptural reliefs; they are the Marseillaise, by Francois Rude; the Treaty of Schonbrunn, by Jean-Pierre Cortot; La Resistance de 1814 or La Guerre, by Antoine Etex; and La Paix de 1815 or the Treaty of Paris, also by Etex.

{Sadly, I can supply postcard illustrations for only two: Marseillaise and Le Guerre. However if your interest in this topic is sincere, you will find satisfactory images on the Internet.}

Oriented at approximately 8° (degrees) 15” (minutes) east of true North, the arch was for decades the tallest structure along the Avenue Champs Elysees. It stands nearly 150 feet wide, 72 feet deep and 164 feet tall. Its fame derives from its history. It honors the casualties of the French wars, its walls are inscribed with the names of the generals who led their soldiers to victory, and beneath the arch there is a crypt in which the remains of the French unknown soldier from World War One lies at eternal peace.

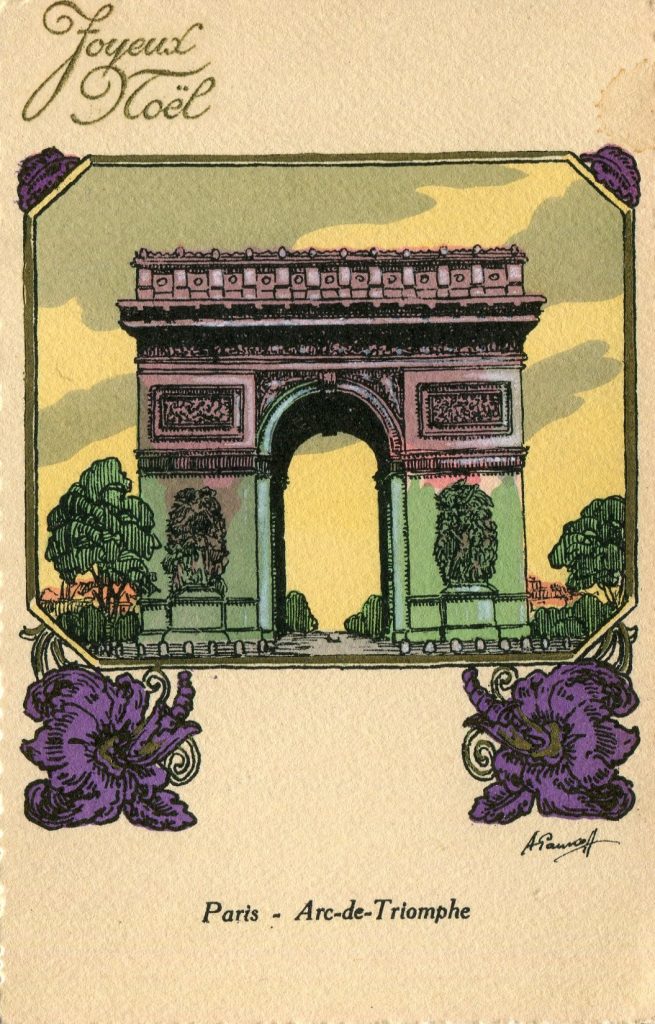

Postcards

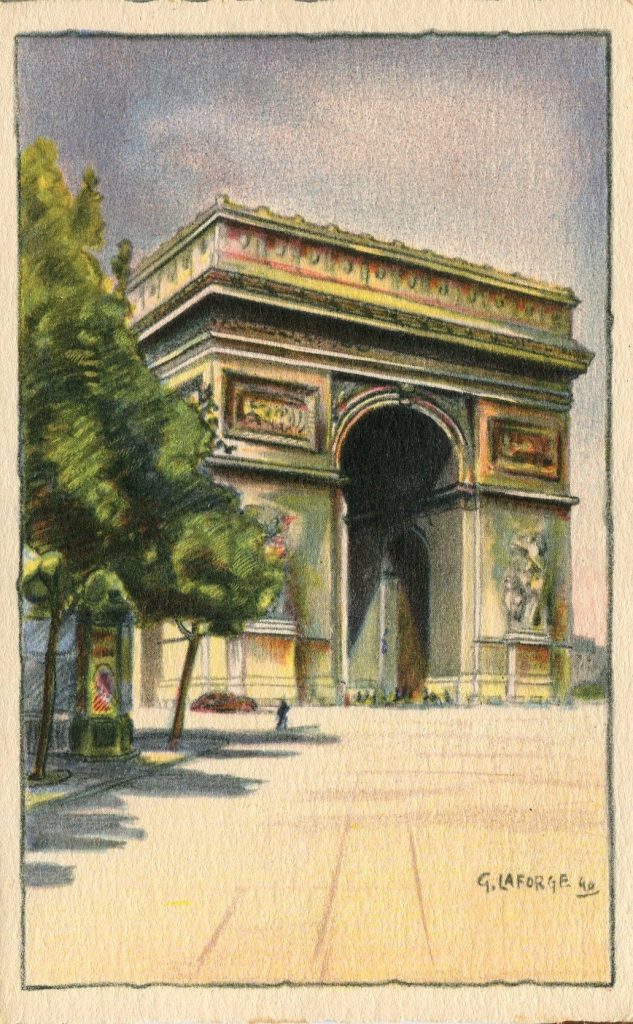

{I surely have lost count of the number of postcards I have showing this arch, but whatever the number, these two are among my favorites. The one on the left is signed by George LaForgé, a well-known mid-20th century street artist, and the one on the right is from a 1907 Noël greetings set of eight showing the Arch and seven other Paris landmarks.}

And, while I’m here, Happy Holidays to all and I’ll see you in January 2021, when I’ll be guiding you through the arches of Rome. It’s the third in the series, so you get three-times your admission price. First, we’ll visit the Titus Arch, then the Septimus Severus Arch and we’ll finish our tour of Rome under Constantine’s Arch.

“Arrondissement” is the French word for one of the districts into which Paris is divided.

Alas, Sir, you are correct, if you are a Frenchman. And, not only in Paris, but throughout the entire country, but that was not the point.

I hate to contradict the writer but there are many other LLs numbered ‘1.’ In 2017 collector John Wood published a superb book entitled ‘LL1 All the LL postcards of the UK.’ A mammoth work which also gives the history of the firm.