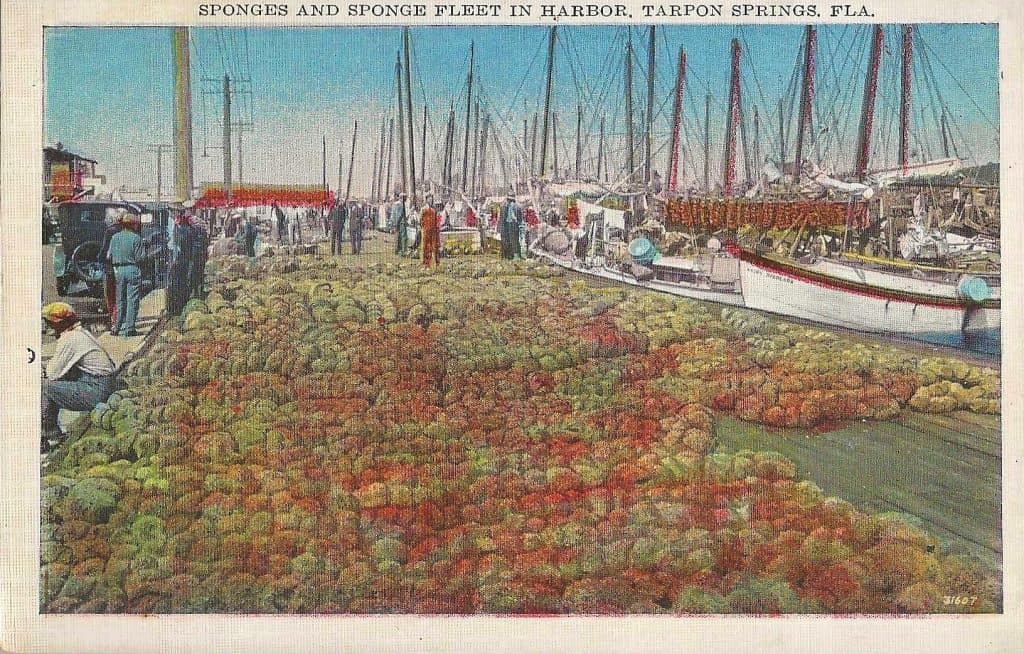

Throughout the world there are cities, counties, and even states that are associated with a product. In the early years of the twentieth century Tarpon Springs, Florida, was such a place. It existed and thrived on an economy built around the sponge fishing industry.

Tarpon Springs will be remembered by generations of visitors and is still an active center of the sponge fishing industry. Visitors from long ago will remember the hundreds or thousands of “drying pans” that were spread across acres of the Florida landscape where sponges were left to dry in the sun.

Other cities with particular product association can be named, such as Detroit, Michigan (automobiles), Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (steel), Richmond, Virginia (tobacco), Akron, Ohio (rubber and tires), and to be a bit cheeky Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (cheesesteaks).

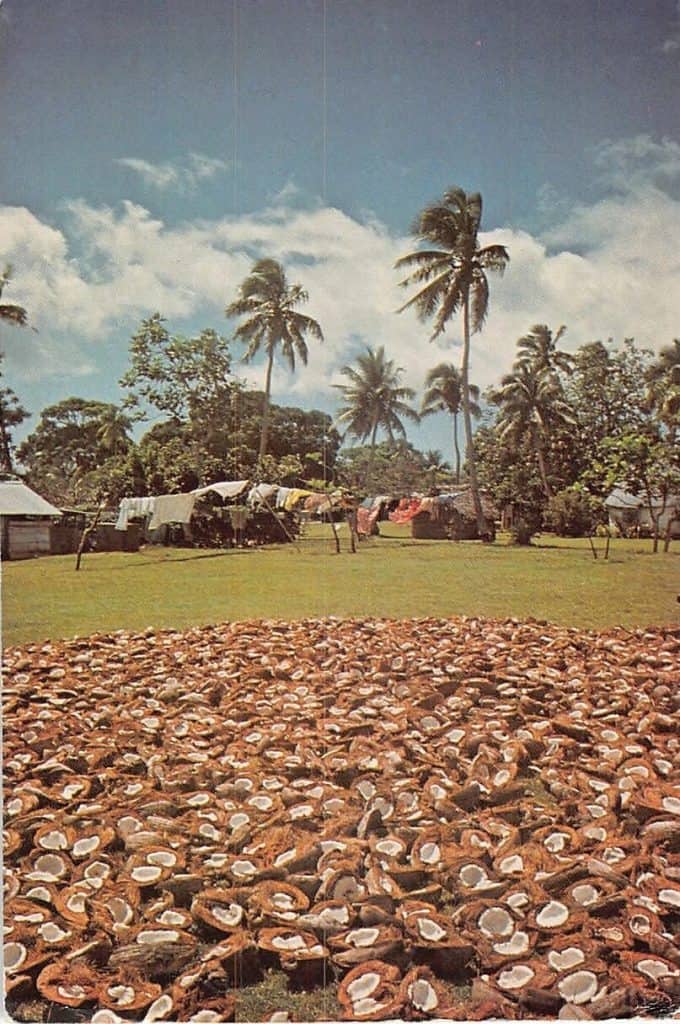

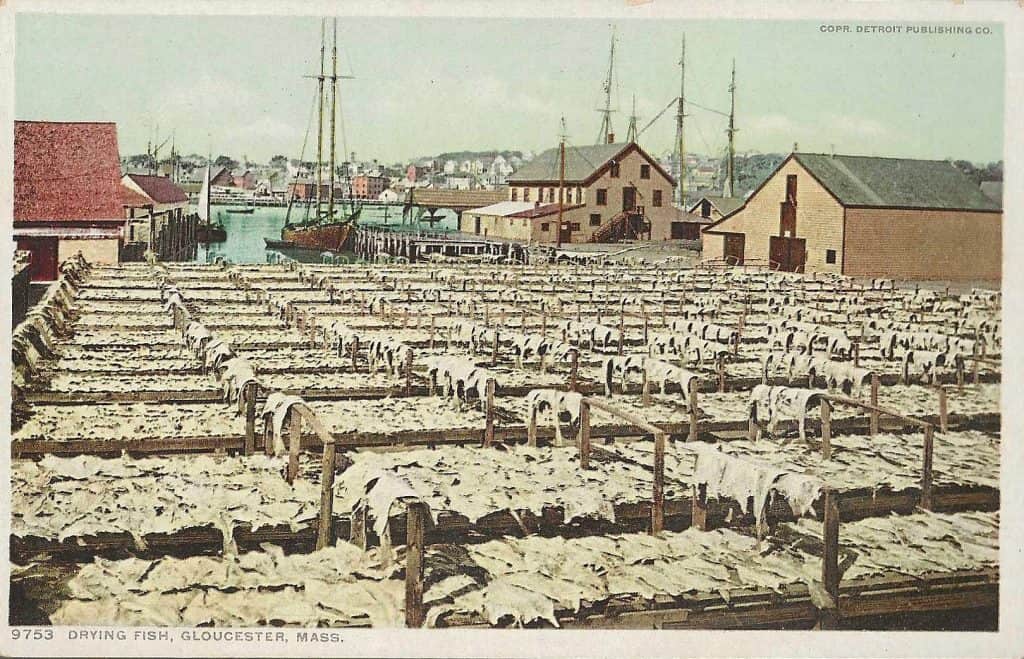

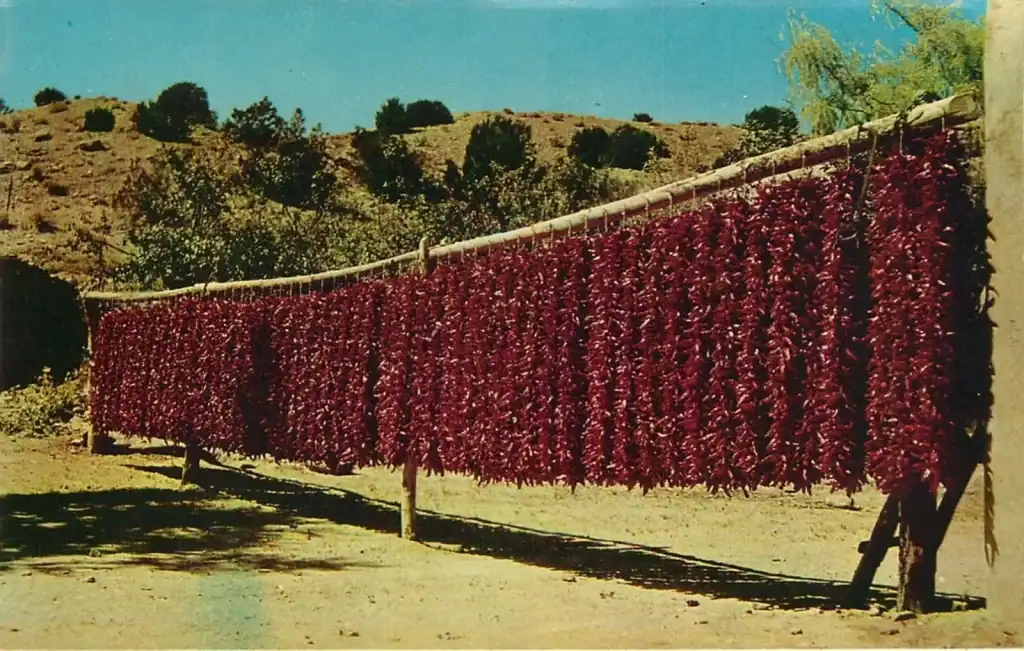

The science that links many of the above-named cities in a common way is dehydration. The first step in processing many products like fruit, fish, and tobacco is removing the inherent moisture. Drying has been critical in food preservation since ancient times to inhibit microbial growth and extend shelf life, with specific techniques including sun drying, oven drying, and advanced methods like freeze-drying or osmotic dehydration.

[Some longtime readers will remember an article about books that were repaired and restored to readability by freeze-drying after being severely damaged by flood waters.]

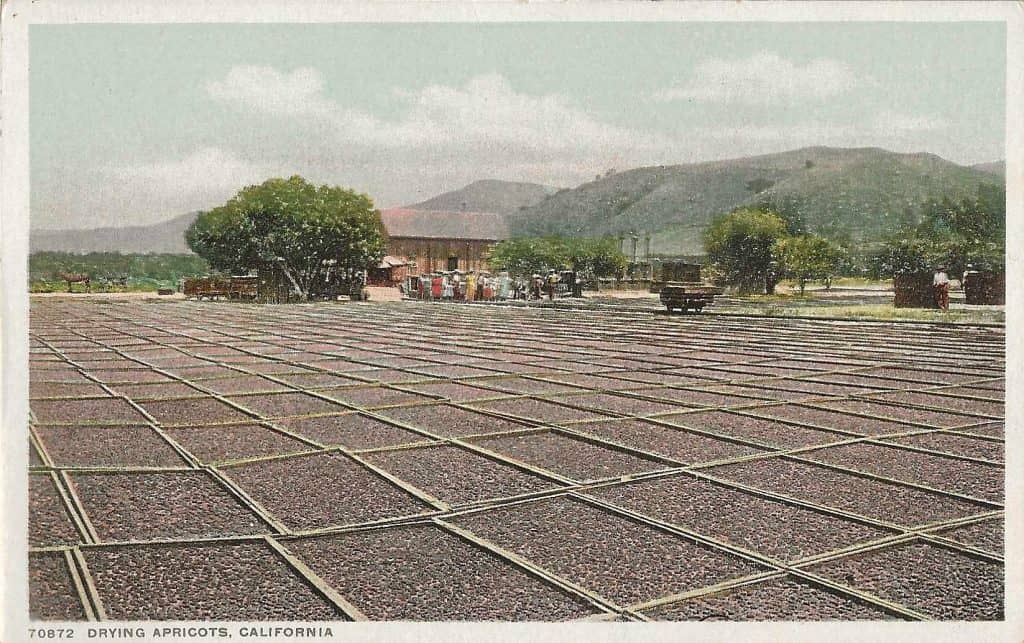

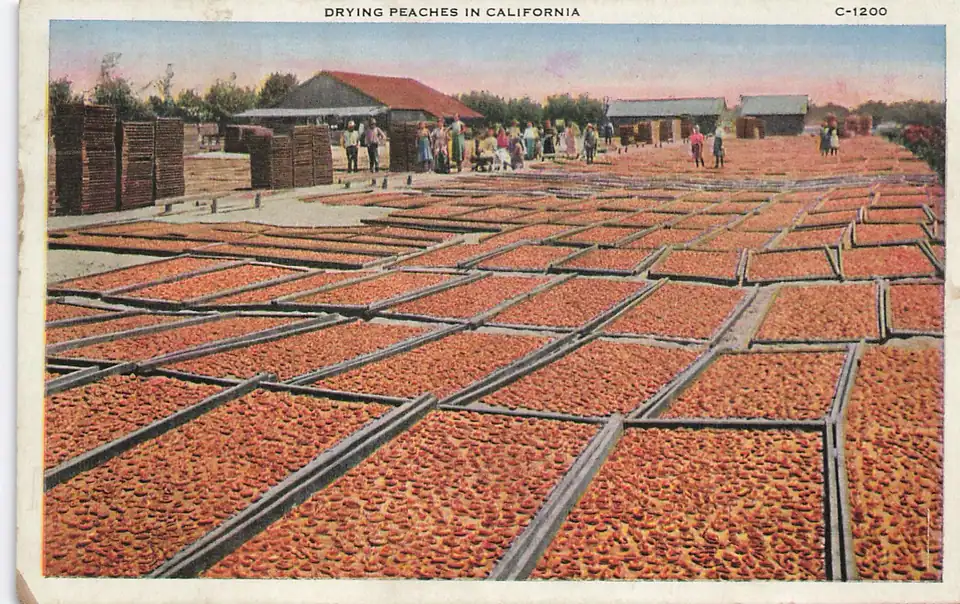

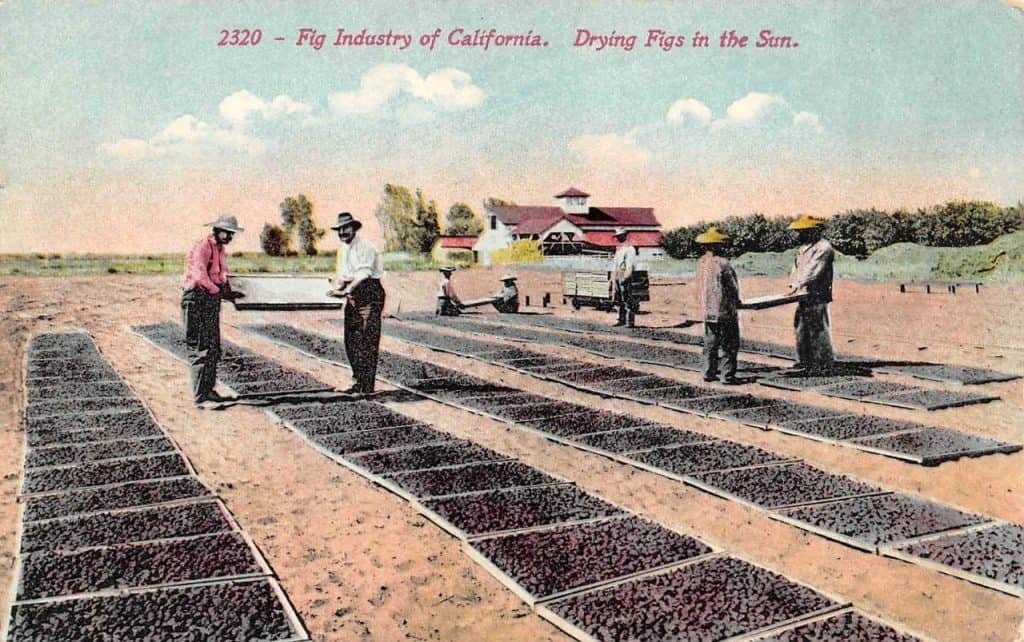

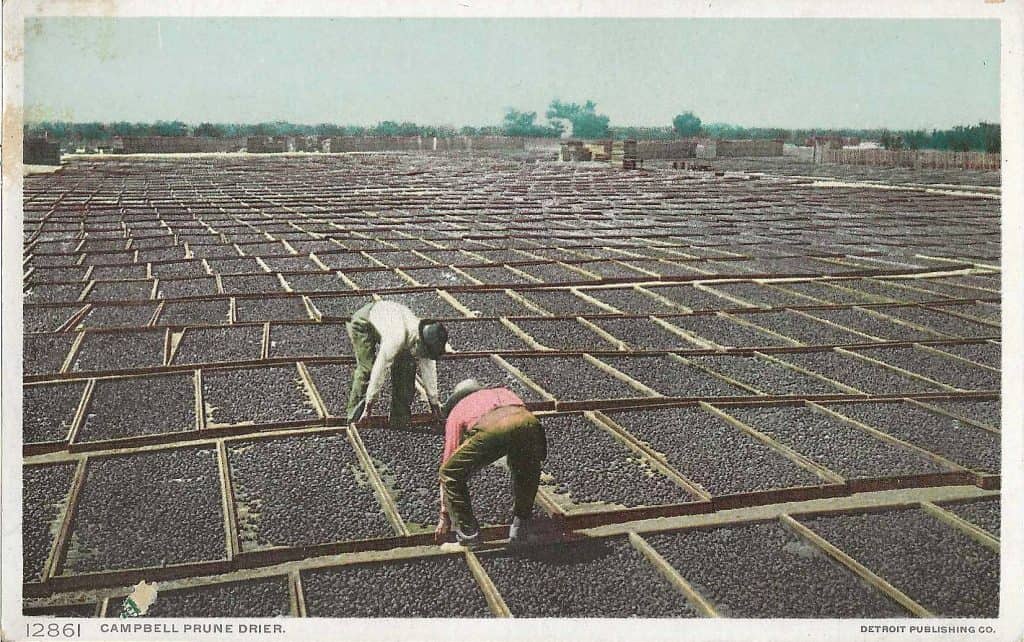

Drying nuts and fruits is one of the oldest preservation arts, a quiet transformation in which moisture is coaxed away while flavor and nutrition concentrate. For fruits, the process begins with removing most of their natural water content, a practice that dates back thousands of years in places like Mesopotamia. Traditionally, this meant spreading fruit under the sun, letting heat and dry air slowly draw out moisture.

As seen on the postcards below, drying apricots, peaches, figs, and prunes in California (at least in the 1940s) was still a preferred method.

Modern producers still use sun‑drying for items like raisins and figs, but large‑scale operations often rely on controlled dehydrators, where warm air circulates evenly around the fruit. This method ensures consistent texture and prevents spoilage. Some fruits are even freeze‑dried, a technique that removes water by turning ice directly into vapor, preserving color and flavor with remarkable clarity.

Fish and seafood, such as cod in Massachusetts and shrimp in the American southland are handled in much the same way.

Nuts undergo a different journey. Unlike dried fruit, nuts are not fresh produce with water removed—they are already the hardened kernels of plants, protected by tough shells and naturally low in moisture. After harvesting, nuts are typically air‑dried or kiln‑dried to reduce their remaining moisture just enough to prevent mold and extend shelf life. This gentle drying stabilizes their oils and preserves their distinctive richness.

Whether it’s a grape turning into a raisin or a walnut settling into storage, drying is ultimately about creating longevity. It concentrates sweetness, safeguards nutrients, and allows these foods to travel across seasons and continents, carrying with them the quiet warmth of the places where they first grew.

Aloha!

So interesting.

But who can forget the best known Californian product as attached below !!!

You need to post the attachment.

I heard it through the grapevine … Sorry 😉

Here it is. California Raisins Commercial (1986)

I never would have thought that reading an article about dehydration would be of interest. Boy was I wrong. I found this article to be quite fascinating and I enjoyed learning about the process.