Marie Hahn

God, Glory and Gold vs. God, Glory and … Dead Bugs

I came upon an article in a Colonial Williamsburg magazine entitled “Putting the Red in Redcoats” by Mary Miley Theobald. Most times articles of this kind offer much more information than you want – they cross your eyes in boredom as they prose on and on with erudite drivel. This one was different. The author wrote with wit and knowledge and delivered her information in a most readable fashion.

“Putting the Red in Redcoats” attracted me because I have always found it interesting that the British army of yesteryear was so confident of its power that they used red uniforms with white belts crossed over the chest as they lined up and prepared to fight. (See the red in one of Harry Payne’s signed postcards, published by Tuck.) I feel that this was tantamount to putting a target on their chest and daring the enemy to hit it. We Americans, on the other hand, tended to hide behind trees while shooting, something we learned from the native Americans.

The red I like is the deep intense red that has been greatly desired throughout history because of it’s rarity. Since supply and demand economics existed as far back as ancient man, it became obvious that only the wealthy could afford it. Wealth usually leads to power, so red was reserved as a symbol of power. Just think of the coronation robes of the British sovereigns or the togas of the Roman senators

The best red dye of the 1400s to 1700s came from the cochineal bug. They live and thrive on the Nopal (Prickly Pear) cactus. This minute bug has a covering of carminic acid. The acid on the carcass of the bug is the valued ingredient in the dye. These bugs are literally scraped off the cactus and dried. The carcasses are crushed then pulverized into a talc-like consistency in order that the substance would dissolve in the dye solvent (sometimes water but most often a variety of diluted alcohol products such as vinegar).

The Cochineal

Often astounded by the red cloth of their Aztec conquests, the Spanish conquistadors who thought of themselves as noble gentlemen, would never stoop to offer a trade, they simply stole what the Aztec had and sent it back to Spain. Oddly enough, cochineal was the second most valuable commodity in the Spanish trade; second only to gold, however it wasn’t until several decades later that traders came and began searching for cochineal.

When others tried to buy the dye, the Spanish made it illegal to sell it to anyone except Spanish merchants. The death penalty is inclined to bring compliance. When you can’t buy what you want one is sometimes motivated to steal it. Pirates targeted Spanish ships not only for its gold but also for cochineal. One such haul by the Earl of Essex gave England enough dye for a year.

Since cochineal looks like dried peppercorns, spies searching in Mexico looked for a dried berry, some for a dried worm or seed, and some even looked for a wormberry. The Spanish, of course, neither denied nor confirmed anything. They forbid everyone from going to Mexico without a permit and refused permits to all foreigners. There was no such thing as free trade at that time in history.

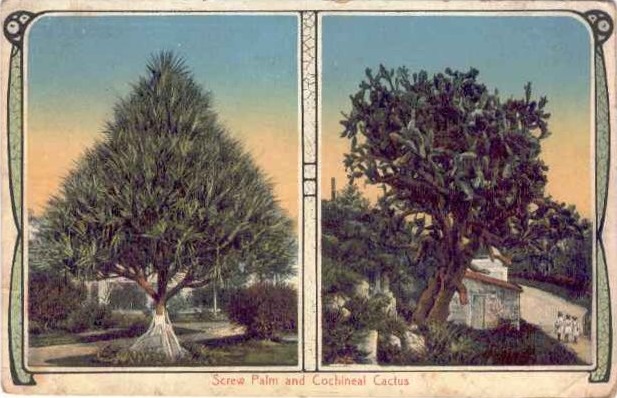

A card from Plants of the American West Series

From a single postcard in a very old set entitled Plants of the American West, you can see the Western Screw Palm (left) and the Cochineal Cactus. Many millions of bug carcasses would have been harvested from a cactus this size.

Once the Spanish influence in Mexico diminished, it became easier to get cochineal. A journal of a British mercantile agent noted that cloth dyed with madder (another kind of red dye) was used for the average British soldier, but fabric dyed with cochineal was reserved for officers – who were required to buy their own uniforms. At the same time, the colonists were using cochineal to color food, dye leather, and in some places even as a medicine. Once chemical dyes became prevalent in the late 1800s, the price of dyed red fabric dropped considerably. Also, it no longer reflected power and wealth. It was simply a pretty color.

My husband is the postcard guy in our family and every time I need an illustration for an article I’m writing he finds me a postcard. That is always the case and this time I thought I had given him a fairly difficult task, but once again thanks to him there are illustrations for this article which originally appeared in my quilt guild newsletter. I truly love quilts of all kinds and the fabrics they are made from. The fabrics that feature a red and white contrast have always been my favorites, and now, as I lay out and cut into a red fabric I can safely assume that no tiny little bugs were harmed in the production of this material.

Once again postcards lead me to an interesting subject. It makes perfect sense to illustrate a quilting newsletter with postcards, but who would have guessed.

The things you learn from collecting postcards and reading postcard magazines!