Bill Burton

I Never Met a Man I Didn’t Like

“I never met a man I didn’t like” is probably a shortened version of what he wrote, and while the actual source is unclear, the meaning of this epigram is not. It sums up what people saw in Will Rogers: honesty, plain-spokenness, and decency.

Born in the Cherokee Nation in the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) in 1879, the youngest of eight children, William Penn Adair Rogers’s family was established enough that the county they lived in was named Rogers County after his father.

He dropped out of school after the tenth grade and worked on the family ranch until 1901, when he and a friend decided to become gauchos on a ranch in Argentina. It didn’t work out, so he moved to South Africa where he caught on with “Texas Jack’s Wild West Circus,” doing trick roping. Within a year he had moved to Australia and was appearing with Wirth Brothers Circus, adding pony riding to his trick roping act.

Rogers typically performed on stage with a partner and his horse. The story goes that, when he muffed a trick, he’d react to it humorously with a slight comment that drew laughs from the audience.

The vaudeville circuit was grueling, as it meant constant travel. At some point he met Betty Blake of Rogers, Arkansas and in 1906 he asked her to marry him. She said no, perhaps not being enthusiastic about life on the road. By 1908, however, she had relented, and they were married in her hometown of Rogers. She accompanied him for several years, but when the first of their four children arrived, she remained at their ranch in Claremore, Oklahoma.

Will’s vaudeville time brought him to the notice of William Hammerstein, who signed him and his horse in for $250 a week to appear at the Victoria Roof — literally a rooftop theater at New York’s Seventh Avenue and 42nd Street.

In 1915 he began appearing in Florenz Ziegfeld’s “Midnight Frolic,” which was held on another rooftop theater, this one the New Amsterdam theater, where Ziegfeld’s “Follies” were performed below. By 1918 he had become Ziegfeld’s (and New York’s) biggest star.

Will began lacing his act with commentary and deft political jabs at any politician in sight. Once, when President Woodrow Wilson was in the audience, his ad-lib roast had not only the audience but Wilson himself roaring.

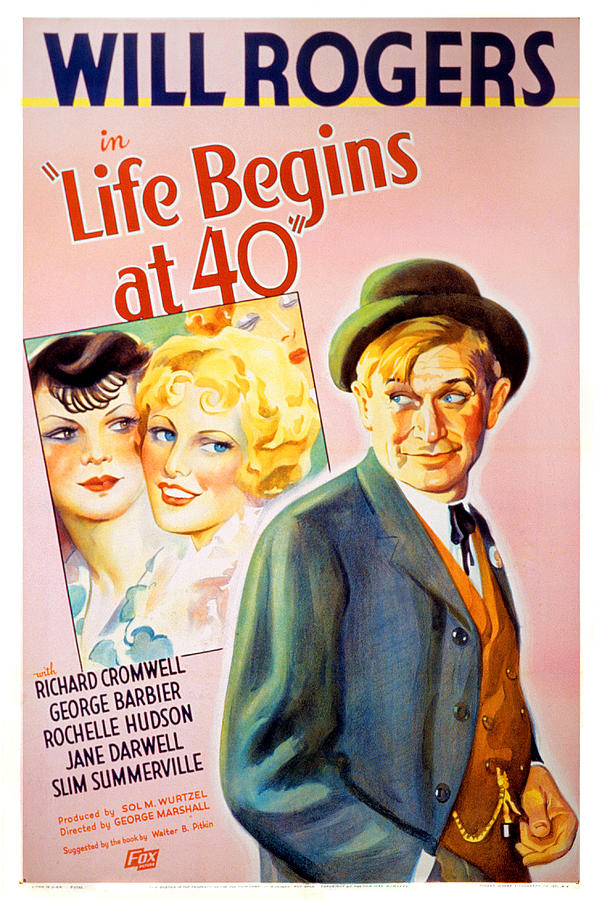

Samuel Goldwyn, the producer and president of Goldwyn Pictures Corporation, convinced Rogers to star in a silent film called Laughing Bill Hyde in 1918. He worked mornings on the film, then returned to the theater for afternoon and evening performances for Ziegfeld.

When Goldwyn asked Will to move to Hollywood to make more pictures, Will agreed but stayed with Ziegfeld for the duration of the New York run of the “Follies” plus the annual tour, which concluded on May 31, 1919. Ziegfeld, who had only a handshake agreement with Will, threw a going-away party and presented Will with a gold watch, engraved “To Will Rogers, in appreciation of a great fellow, whose word is his bond.”

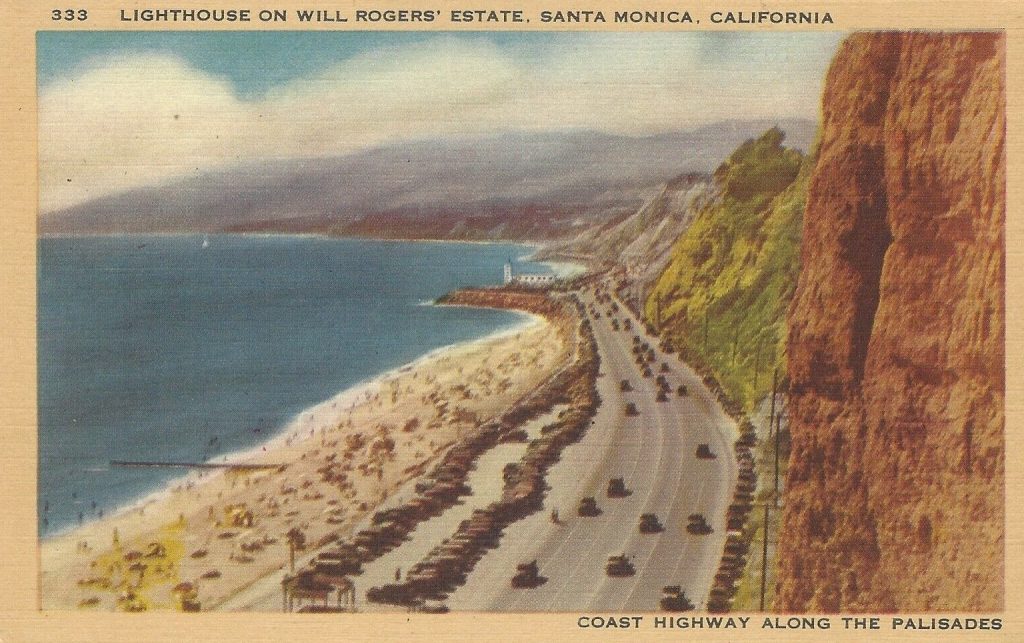

Will and Betty bought property in the Santa Monica mountains, in what is now the Pacific Palisades neighborhood. Ultimately they built a 31-room ranch house on 186 acres with a polo field, stables and other provisions for horses. The house itself had a commanding view of the ocean across the Pacific Coast Highway. It was to be their home for the rest of Will’s life.

Will’s abundant energy extended beyond movies. He had occasionally written short articles for newspapers, recycling material from his stage shows, but in 1922 The New York Times began syndicating “Weekly Articles,” a column that went daily in 1926. He was moving away from material that many people had heard at his stage appearances. It has been estimated that in his lifetime, Will wrote 4,000 columns.

For almost ten years, between movies, Will toured the country and the world, giving talks (not lectures because, he said, “a humorist entertains but a lecturer annoys”). Some of these appearances were charitable where he raised money for relief of catastrophic events, and he always made friends wherever he went.

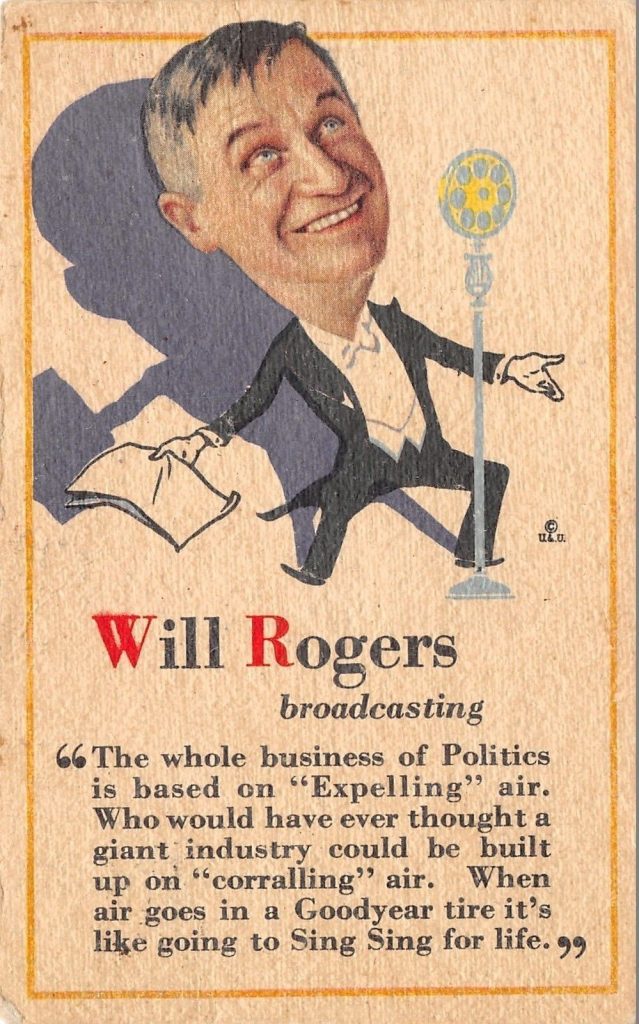

As radio became more common in the late 1920s, Will began making occasional appearances. He supported Calvin Coolidge but in 1928 he went too far in making fun of “Silent Cal” which the President did not appreciate. He campaigned for Franklin Roosevelt in 1932 but is remembered more for his remark that “I belong to no organized political party; I am a Democrat.”

In 1933 Will began a regular Sunday evening half-hour show sponsored by the Gulf Oil Company. When station breaks, commercials, and other interruptions caused him to lose track of time, he would sometimes be cut off in mid-sentence. To cue himself, he bought an alarm clock that would ring when time was getting short. The alarm clock became such a well-known prop that the show was sometimes called “Will Rogers and his Famous Alarm Clock.”

Will’s enthusiasm for aviation began early in his career. He befriended early air pioneers and supported Billy Mitchell during his 1926 court-martial over Mitchell’s outspoken support for air power over sea power. He made two round-the-world airplane trips and befriended Charles Lindbergh’s advocacy for using airplanes to move mail across the country. His visits to Europe convinced him that air travel was the wave of the future.

This interest brought Will into contact with fellow-Oklahoman Wiley Post, with whom he toured the southwestern United States in July 1935. In early August, Post wanted to survey a mail route to Russia via Alaska. The two men planned a flight to test various routes in Post’s single-engine Lockheed hybrid pontoon-equipped plane.

For nine days they flew over Alaska. On August 15, they left Fairbanks for Barrow, Alaska’s northernmost settlement. After making a refueling stop at a small lake some 15 miles short of Barrow and getting directions, they took off.

A sudden mechanical failure caused the plane to nose-dive into the lake, instantly killing both Post and Rogers.

My father has a poster featuring a photo of Rogers alongside Will’s quote “Everybody is ignorant, only on different subjects.” One of the joys of collecting postcards is the fact that the scenes and text help eliminate some of the viewer’s ignorance!

There are books and books containing Will’s comments and his 4,000 or so newspaper columns.Your poster had one of the better ones, I just couldn’t figure out how to work it into the article.

What a great life he had! Too bad it was cut short.

Will Roger’s home and ranch was given to CA in 1944, and is still standing. It is a state park that people can visit.

I should say that the ranch house is closed during this pandemic…

You’re right, the house is closed for the duration. The park though, is open.