Eleanor “Ellie” McCrackin

Ships of the Italian Line

the First, the Best, and the Last.

The Italian ocean liner SS Rex was laid-down and completed in record time. Launched in 1931 and put into service on the North Atlantic and South American circuit, the world stood and marveled at the Rex, for it surpassed all visions of sea-travel in that era.

SS Rex

By 1933, Rex had won the westbound Blue Riband and managed to hold it until the French ship Normandie captured the prize in May 1935 with a crossing that bested the Rex by nearly 10 hours.

Originally built for the Navigazione Generale Italiana (an Italian shipping concern founded in 1881), Rex came under high scrutiny in the later stages of construction and some rather significant financial concerns came to the attention of the state. The authorities, in turn ordered a merger that ultimately created the Italian Line.

The outbreak of the Second World War had little effect on the Line’s commercial service in the Mediterranean, however when Italy entered the war in June 1940, the corporate leadership thought it necessary to lay-up the ship for safe keeping.

Then came September 8, 1944. The British Royal Air Force found Rex in the Adriatic, off the shore of the city of Koper. In a matter of a few hours the British hit the ship with more than 120 incendiary rockets. The ship caught fire from bow to stern and burned for nearly four days. Its demise came when it rolled onto its port side and sank. The indignity of it all was that the pride of the Italian Line lay in the mud with no thoughts that it should be salvaged until 1950 – six years after the war ended.

* * *

Friday, January 23, 1953. A new passenger liner was about to complete her maiden voyage. She entered the Hudson River from New York Bay, headed upriver to Pier 84, and berthed only minutes behind her noon-day scheduled arrival. The 30,000 ton, SS Andrea Doria was the first new Italian passenger liner to be seen in 20 years.

The following morning the New York Daily News published this photograph in its standard back-page photo array, with the caption: “Distinguished Visitor.”

Distinguished Visitor

Back in the homeport of Genoa in 1953, the executives of the Italian Line who did not sail on the maiden voyage were bursting with pride over the greeting Andrea Doria received in New York. The flotilla of welcome-vessels included several of the city’s fireboats. Many of those left behind had much on their minds. They continued to work with the authorities at the Ansaldo Shipyard in Genoa at a furious pace to get a sister ship ready for launch in less than four months. The SS Cristoforo Colombo was scheduled for its maiden voyage in early 1954. Sadly, it was do or die. The Italians were in a race with the world. They needed to jump-start a slow economy that would ease the devastation that World War II left behind.

SS Andrea Doria

Between her first arrival at New York in January 1953 to July 1956, Andrea Doria had completed 53 westbound crossings of the Atlantic. On the 17th of July she left Genoa for New York under bright-sunny skies without an inkling that disaster was on her horizon.

While in service for only three and a half years, on July 25, 1956, while Andrea Doria was approaching the coast of Nantucket, Massachusetts, bound for New York City, the eastbound MS Stockholm of the Swedish American Line collided with it in what became a notorious maritime disaster. Struck in the side, the top-heavy Andrea Doria immediately started to list severely to starboard, which left half of its lifeboats unusable.

The shortage of lifeboats could have resulted in significant loss of life, but the efficiency of the ship’s technical design allowed it to stay afloat for over eleven hours after the incident. The good behavior of the crew, improvements in communications and the rapid response of other ships averted a disaster similar in scale to that of Titanic.

While 1,660 passengers and crew were rescued and survived, 46 people died with the ship as a consequence of the collision. The evacuated luxury liner capsized and sank the following morning. This accident remains the worst maritime disaster to occur in United States waters since the sinking of the SS Eastland in 1915.

The incident and its aftermath were thoroughly covered by the news media. While the rescue efforts were both successful and commendable, the cause of the collision with Stockholm and the loss of Andrea Doria generated much interest and many lawsuits.

Largely because of an out-of-court settlement between the two shipping companies during hearings immediately after the disaster, no determination of the cause was ever published. Although greater blame appeared initially to fall on the Italian liner, more recent discoveries have indicated that a misreading of radar on the Swedish ship initiated the collision course, leading to errors on both ships.

For any of Postcard History’s readers who live in the Delaware Valley, it is likely that the most famous of the survivors were Philadelphia Mayor Richardson Dilworth and his wife Anne.

* * *

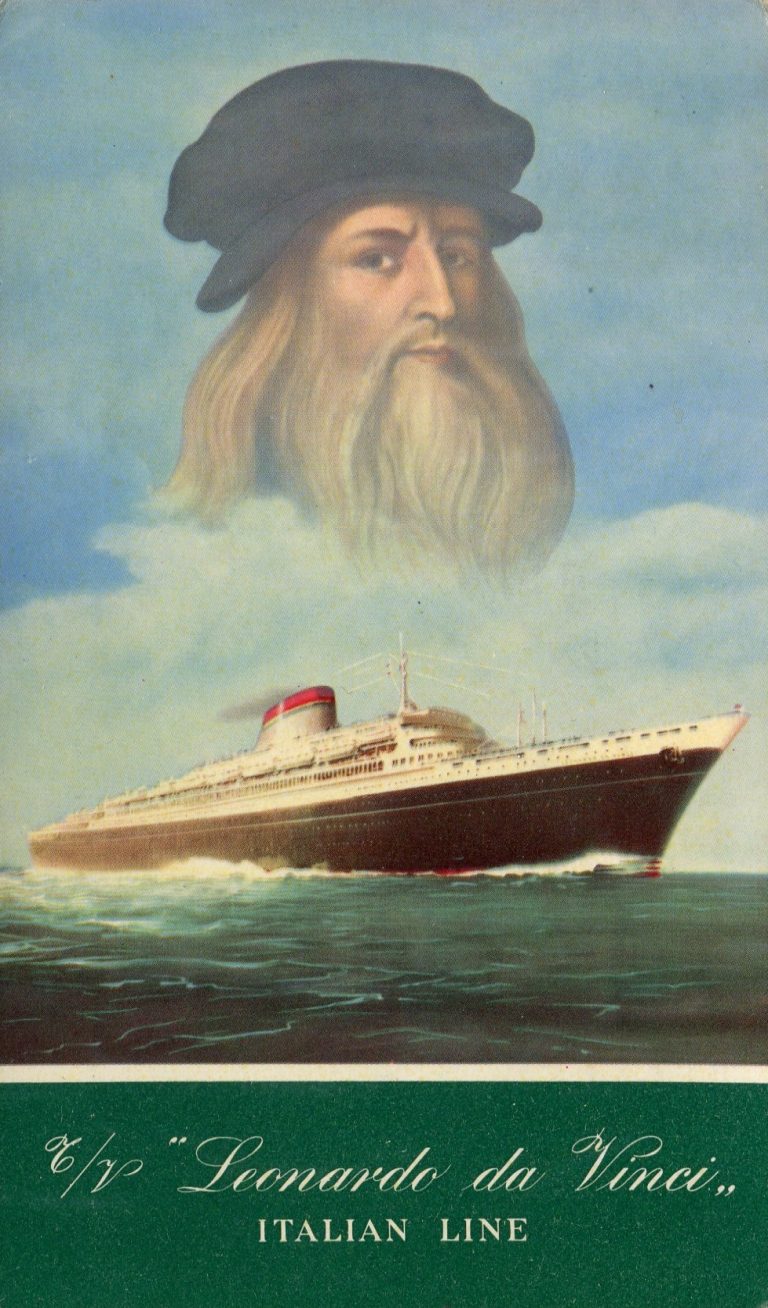

Leonardo da Vinci

[Special note from the author: I suppose, at this point, an advanced apology is in order, for I preface my summary with a rhetorical question based on a stereotype. I intend no disrespect.]

Have you ever tried to change the mind of an Italian once a decision is made? Aren’t Italians among the most stubborn nationality you know? First the Latins and then the Romans gave no quarter, they were followed by generations of Romans who are a grand conglomerate of blood-lines from the celts, the Lombards, and the Etruscans. The stereotype is footed by determination. “We are, We can, we will!”

In the late 1950s, more than five years after the loss of Andrea Doria, the status of the Italian Line balanced on a razor’s edge deciding which way to fall. When the corporate directors announced a new contract with the Ansaldo Shipyard for a replacement vessel named Leonardo da Vinci, not one contrary voice was heard. The decision was to look to the past, not the future.

When at last in 1976 there was no future, Leonardo da Vinci attained the status of last descendant – passenger service on the Italian Line was no more.

This is such a heartening story. It reminds me that there will be life “after Covid” and that it will include cruises and adventure.

Also, I learned something new about the history of the steamship business.

Thanks.

I have a rather hard to get postcard of the Andrea Doria sinking off Nantucket on July 25, 1956. The card was published by Bromley and Company, Inc., Boston 16, Mass. If it would be helpful to you, I would be glad to send you a scan of this card. Please let me know.

I’m reminded of the Seinfeld episode in which George loses a bid for an apartment to an Andrea Doria survivor.

Mr. Shav La Vigne (see his comment here) has shared the card he mentions. Click on the thumb-nail image to enlarge.